Famously, nonprofits depend on people. But the sector has underinvested in human resources (HR), even as talent enhancement has become imperative. The dual pandemics of COVID-19 and structural racism have laid bare unhealthy and unsustainable work environments that leave nonprofit teams disengaged and experiencing burnout.1 The world of work is waiting to be reimagined.

When it comes to organizational management, the HR function often gets scant attention. Yet it is a vital function that touches the entire life cycle of staff. It is time, I would argue, to liberate HR. What do I mean by this?

Fundamentally, to me, liberating HR means three things:

- Reframing HR language

- Repositioning HR roles

- Transforming our paradigm about HR

These three major shifts can help dismantle HR’s racist history, as well as mine the strategic opportunity in HR and reshape the multiple roles embedded in the HR function.

Reframing HR Language

How can reframing language help liberate HR?

Imagine the mental shift that results from aligning the HR language we use with the language of the liberation movement and racial reckoning that have engulfed us. Although this reframing is not new and has already started, we have a long way to go.

Writing this article is both a heart-wrenching and a heartwarming moment for me as I traverse my own personal racial equity journey. My career has centered on organizational development, a chunk of which was in HR in both the private and the public sectors. In my transition from the private to the public sector, I realized that there were more shared HR practices between the two sectors than differences. Those shared practices—well intentioned and values-based as they may be—often support white supremacist norms. Indeed, I recognize that I have been complicit—even if unwittingly—in perpetuating those norms. So it is with deep commitment that I aspire to be part of liberating HR.

Like many areas of work, the socioeconomic and political environment has shaped HR. As we travel through the history of human resources management, a closer look reveals that alongside the benefits of HR work, there was the underbelly of paternalism and white supremacist norms resulting in disproportionate negative impact on Black people and other people of color. The language used in the world of HR, and the world in general, evoked at times subtle, and at times overt, racism.

The beginnings of the field can be traced back to the early 19th century during the industrial revolution, when two Englishmen (Robert Owen and Charles Babbage) developed the rudiments of what would later become human resources. It was a century later, however, faced with rising labor union strike activity, in the 1910s and 1920s, that the formal field of “Human Resource Management” was born.

A few companies began to realize that employees are motivated by more than just money. Benefits, job security, and participation plans were put in place to win employee loyalty, and—executives and HR managers hoped—to forestall unionization.

“Welfare Capitalism” gained prominence in the 1920s, the term itself evoking a sense of paternalism, a white supremacist norm. People were considered “assets.” An asset is anything which is owned by an entity to derive service in the future and is a legally enforceable claim.2 If people are assets, then organizations expect to profit from them, and they are carefully tracked as “headcounts”—another basic HR term that treats people as part of a herd that needs to be accounted for.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression brought record-high unemployment, which only truly ended with the full-scale mobilization that World War II required. In the drive to win the war, the country had to solve phenomenal talent shortages by employing women to take on a variety of jobs: streetcar conductors, electricians, welders, and, yes, riveters. Yet, gender inequity persisted and the military remained racially segregated until President Harry Truman ordered integration of the armed forces in 1948. After the war, HR practices in the military carried over to the corporate world, with the system’s values upheld by white males.

The Civil Rights Movement has changed HR—somewhat. Notably, civil rights legislation—such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990—have resulted in HR “compliance” strategies. But that’s far from building liberatory workplaces.

Today, as employment has become more precarious due to a “gig economy” of short-term contracts and freelance work, this too has affected HR—and not in a good way. The key concept has been optimization—achieving the best work for the most gain, as if people were machines that can be revved up. The term “human capital” materialized, as if people represent currency. All these developments essentially begged the question: “Are humans resources?”—a question insightfully raised by NPQ’s Jeanne Bell.

The racist roots of human resources management that reinforce structural racism in the workplace are mirrored in language. Because language is evocative of identity, language matters in liberating HR from its racist roots. As simple as it may sound, reframing language is difficult. It is reminiscent of learning a new language. It takes practice, commitment, and more practice.

Let’s start with the term Human Resources. How about changing it to People and Culture, which is already used by some organizations? PAC instead of HR. This shift moves us from a view of people as a commodity to an outlook that lifts the wholeness of people and the significance of the space they inhabit. Tom Haak named position titles that represent that shift, such as Talent Champion, Learning Ambassador, Transformation Lead, and Partner in Change.

Rethinking the HR Basics

Another shift in language centers on the terms as well as the messaging used in specific HR practices and functions.3 A lot of HR work concerns what I might call the basics—recruitment, retention, compensation, and performance. Liberating HR would involve changes in language and practice in all these areas. In my years of consulting with clients on people and talent issues, I have seen, happily, that some nonprofits have begun to adapt parts of the language and practices listed below.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Recruitment

- Job Descriptions: Evaluate the job description for class bias; use language that is culturally and gender inclusive.

- DEI Statements: The law requires an Equal Employment Opportunity Statement; add your organization’s DEI statement or a value statement that reflects your commitment to equity.

- Outreach: Conduct focused outreach directed towards communities of color. Ensure there are at least two BIPOC candidates in the finalist pool; a 2016 Harvard Business Review article reported the results of one study of 598 job candidates for university teaching positions, including 174 who received offers. When there was only one woman or BIPOC candidate in the hiring pool, those candidates did not get hired. But if there were two or more women or BIPOC candidates in the hiring pool, the likelihood of one of them being hired was similar to that of the white males in the pool getting hired.

Retention

- Onboarding: Include discussion of organization culture and norms; an honest overview of racial equity work (including recognition of shortcomings), organization functions, and how decisions are made.

- Support Strategies: Employees of color in predominantly white organizations can face a great deal of social isolation and bias within the workplace. Examples of support strategies are learning about their perspective and worldview, including race; identifying their interests; helping them build social networks; connecting them to affinity groups, professional associations, and other social groupings that support employees of color; and providing mentorship.

- Stay Interviews: Conduct regular check-ins.

Compensation

- Job Posting: Income secrecy is a divisive cultural tool that derives from free market capitalist logic, which benefits the one percent. Everyone, especially funders, need to see how such practices are furthering inequity.

- Pay Equity: People are handsomely paid for analyzing financial data, but not for work involving emotional labor; a move to jobs that require increased cognitive labor results in an average of 8.8 percent wage boost, but a shift to positions that demand higher emotional labor results in a 5.7 percent cut.

Performance

- Team Contributions: Shift language from Performance Management to Team Contributions. Consider eliminating performance ratings. A recent NPQ article illustrates that the practice of performance ratings can be traced back to the management of enslaved people. Even today, performance indicators often are used to maintain hierarchical work norms rather than build a culture that fosters two-way feedback and accountability for one’s growth and staff development. A better alternative are self-assessments that set the stage for conversation of what is working and not working—engaging staff and colleagues in conversation regarding how to improve organizational performance.

- Talent Enhancement: Focus on strengths instead of deficits in planning and implementing growth strategies; infuse learning opportunities with a DEI lens; ensure equitable access to learning opportunities. A focus on strengths does not mean ignoring the need to address learning edges. By focusing on strengths, a work environment is created that leverages team members’ strengths to address areas where improvement may be needed.

Repositioning the HR Role

How does role repositioning liberate HR? For role repositioning to effectively shift HR practice, it must rest on the following principles:

- The HR position is a strategic partner to, and reports to, the highest level of decision-making in the organization.

- Its responsibility is bolstered by the appropriate level of authority. The level of decision-making incumbent in its role supports its authority level.

- The HR role is not monolithic and therefore its scope must encompass the key pillars of the function—the distinct competencies or specialties around strategy, organizational design, talent search, talent enhancement, staff engagement, rewards and recognition, and the leadership pipeline.

- It is not a solo act. It requires the collaboration of those responsible for guiding and advocating for staff and requires at least one other HR team member.

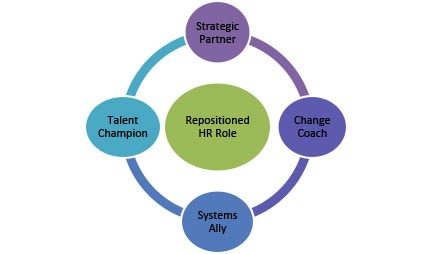

What would a repositioned HR role look like? Because the scope of HR is encompassing, it warrants multiple complementary roles. The role architecture that is proposed here aligns best with the paradigm shift described earlier and was inspired by the writings of Dave Ulrich.4

- Strategic Partner: Develops and aligns strategies with mission.

- Change Coach: Strengthens change capability within the organization.

- Talent Champion: Develops strategies and helps implement actions that enhance team contribution.

- Systems Ally: Creates and delivers effective and efficient HR processes and services tailored to the organization’s unique needs.

Towards a New HR Paradigm

Calling for a paradigm shift sounds good, but what does it require? It was Thomas Kuhn—the well-known physicist, philosopher, and historian of science—who developed the notion of a paradigm shift, which he described as “an important change that happens when the usual way of thinking about or doing something is replaced by a new and different way.“5

Kuhn adds that paradigms only shift when the paradigms we use fail to make sense of the world. We are already seeing this in HR. Back in 1998, in “A New Mandate for HR”6 David Ulrich posed the question: “Should we do away with HR?”

Despite some doubts about HR’s contribution to mission, Ulrich affirmed that HR has never been more necessary. The community needs effective organizations that make a difference. The way organizations get things done and how people are treated are central to achieving that goal.

How might HR achieve that goal? Imagine an HR department that did the following:

- Centrally focus on aligning strategy and talent by moving away from purely administrative, policy-focused, and procedural concerns.

- Infuse HR with a diversity, equity, inclusion, and racial justice lens.

- Co-create solutions up and down the organization.

- Sustain organizational culture—serving as stewards of work-life wellness.

We can act like the frames of HR we use still make sense. But we know better. The time to develop a liberatory HR is now.

1 Jennifer Robinson, The Emotional State of Remote Workers: It’s Complicated, Gallup, December 15, 2020.

2 Investment in Human Resources, MBA Knowledge Base, 2021.

3 Desiree Williams-Rajee, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Recruitment, Hiring and Retention, Urban Sustainability Directors Network, October 4, 2018; Mala Nagarajan and Richael Faithful, Brave Questions: Recalculating Pay Equity” Network Weaver, July 8, 2020; Andrew O’Connell, “Emotional Labor Doesn’t Pay,” Harvard Business Review, September 29, 2010; Jasmine Hall, Reimagining Compensation Decisions Through an Equity Panel, CompassPoint, December 11, 2019.

4 Dave Ulrich, Human Resource Champions: The Next Agenda for Adding Value and Delivering Results, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 1996.

5 Tania Lombrozo,“What Is a Paradigm Shift, Anyway?” Cosmos & Culture, Commentary on Science and Society, National Public Radio, July 18, 2016.

6 Dave Ulrich, “A New Mandate for Human Resources,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1998.