November 30, 2019; NPR

It is (or perhaps it ought to be) a question that nonprofits regularly ask themselves: What elements of our practice have we failed to question lately? Are we doing anything that just doesn’t make sense beyond a surface level?

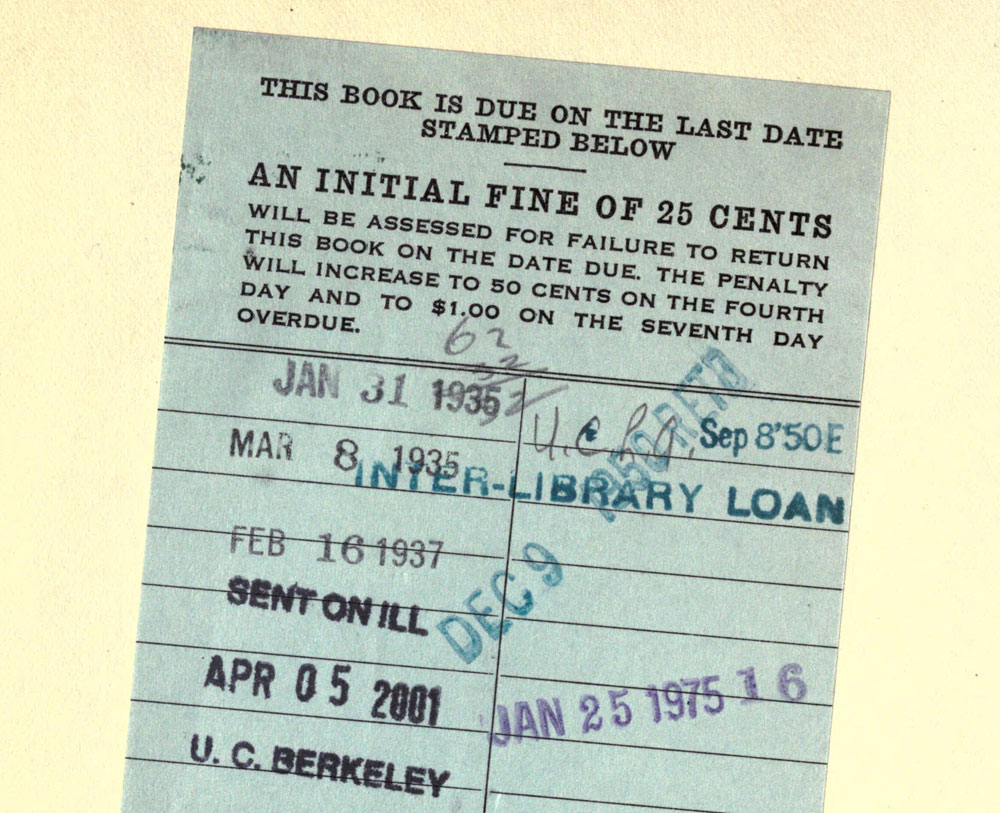

For the past couple of years, public libraries across the US have been asking themselves this question and found a common answer: late fees. Over 450 public libraries across the US have decided they will no longer fine patrons who return books and other items past their due dates.

More libraries are considering the switch. Variations on “fine-free” exist; some libraries eliminated late fees only for children, some offered alternative forms of payment (L.A. County lets kids “read away” their fines), and others created “amnesty days” when patrons could return late materials without being charged.

Whatever the mechanism, the principle remains the same: late fees discourage patrons, disproportionately those with lower incomes, from using a resource that is supposed to be free and open to all. And that rankled librarians’ sense of mission.

“This is honestly the most exciting thing to happen at CPL since I’ve been here,” said Chicago Public Library branch manager Lisa Roe. “It’s amazing to ‘walk the walk’ with regard to free and open access for all patrons.”

The movement toward fine-free access hit a tipping point this year. At their midwinter meeting in 2019, the American Library Association issued a resolution. They added a statement to the Policy Manual declaring, “The American Library Association asserts that the imposition of monetary library fines creates a barrier to the provision of library and information services,” and recommended that libraries “move towards actively eliminating them.”

Library fines have long been justified on two counts: they contribute to library operating revenue, and they motivate patrons to return items on time. However, after a few studies were done and a few libraries enacted this program, a revelation emerged—neither of those justifications were true.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Chicago Public Library, for instance, offered a couple of amnesty days before going fine-free on October 1st of this year. On those days, when patrons could return items to the library and renew their cards without fear of fines, hundreds of thousands of items were returned. In 2012, for example, CPL waived $ 641,820 worth of fines and got back over 100,000 overdue items, valued at over $2 million. What’s more, nearly 30,000 users renewed or applied for cards, proving the ALA’s point that fines prevent access.

Chicago’s adoption of a permanent fine-free policy bore out this point. Returns went up 240 percent in three weeks. Fines didn’t bring materials back to the library; they discouraged returns—not just of materials, but of patrons.

What’s more, major cities like Boston and San Diego found they were spending more money to collect late fees than they were getting back. Fine collection, said a library commissioner, “really wasn’t a revenue stream.”

Linda Poon at City Lab reports that research going as far back as the 1970s or 1980s shows that library fines didn’t function the way libraries claimed they did. She talked to Curtis Rogers, communications director for the Urban Libraries Council, about the risk involved; libraries, he said, need to consider whether they can handle it—and as we’ve seen, the “risk” is far less prevalent than common attitudes would have us believe.

NPQ has written in the past about nonprofit “risk” and how it can be an opportunity for leadership. In the coming weeks, we will see work from Cyndi Suarez about the racialization of risk, and how some people are categorized as greater risks for investment, leadership, and responsibility.

Many librarians who advocate eliminating fines have declared it isn’t their job to teach responsibility—and in fact, it seems the greatest “risk” involved for many libraries is the influx of patrons who have hitherto been kept out. Fines have played the role of onerous bureaucracy or work requirements, keeping people most in need from public services through shaming and systemic habit.

So ask yourself: What doesn’t your nonprofit need to be doing?—Erin Rubin