“Everyone should know, including the president, this is what real locker room talk is.”

—Joe Lockhart, Executive Vice President, NFL

Last Sunday, politics entered the field of NFL games at a volume never seen before. As reporter Nancy Amour, writing for USA Today, relates, “The scenes, and the statements, were extraordinary. Empty sidelines in Nashville and Chicago. Jacksonville owner Shad Khan standing arm in arm with his players…Oakland Raiders owner Mark Davis eloquently explaining his change of heart about players protesting during the national anthem.” Over 250 people, including not just athletes but even team owners, participated in protest on the field, a scale never before seen in the 97-year-old history of the National Football League. The remarkable scene was unprecedented in its collective scope and scale, but it also builds on a very long history of sports activism.

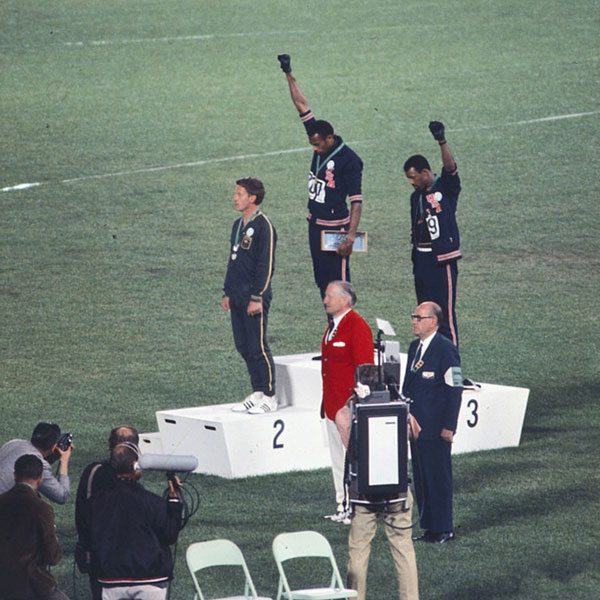

We know many of these images and stories as iconic: Muhammad Ali refusing induction to the U.S. army, John Carlos and Tommie Smith raising their fists in a black power salute after winning medals at the 1968 Olympic Games, Curt Flood suing Major League Baseball to end the so-called “reserve system” that suppressed player salaries, Billie Jean King joining with eight other women tennis players in 1970 to form their own tennis tour and ultimately achieve equal pay. We celebrate such moments now—the Billie Jean King story is currently showing in your local movie theater, starring Emma Stone—but the athletes who stood up for social justice were rarely fully appreciated in their day for the extent to which they risked their careers.

Sports may seem trivial to those who are not fans, but beyond their entertainment value and the extraordinary physical achievements they put on display, sports provide a stage for some of our most powerful collective stories.

Who among us doesn’t know that Jackie Robinson integrated baseball? It may not be fair, but surely more people know who Jackie Robinson is than recall Ezell A. Blair, Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain, Joseph A. McNeil, and David L. Richmond—the four people who started the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins. Moreover, as educator Peter De Witt argues, team sports can teach important lessons that speak to how to negotiate the balance between individual achievement and collective goals. Asking sports and politics to be separate from each other is a fool’s errand, because sporting events are in fact key sites where our collective identities are forged in the first place.

Our athletes, in short, have long played an important role in social narratives and national culture off the field. That said, they have often paid a high price when taking a stand. As a 2008 Smithsonian magazine profile of Carlos and Smith noted, “For 40 years, Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos have lived with the consequences of their fateful protest.” The immediate response to Ali’s refusal to serve in the army during the Vietnam War was to strip him of his world championship boxing title at the pinnacle of his career. As for the “Original 9” who created the Virginia Slims tennis tour, each, as Billie Jean King relates, was threatened “with suspension and expulsion.”

As for Flood, the title of an Atlantic magazine feature penned a half-dozen years ago, says it all: “How Curt Flood Changed Baseball and Killed His Career in the Process.” To understand how different times were, consider that in 1971 baseball pitcher Vida Blue won the American League Cy Young award, given to the League’s most valuable pitcher, and took home all of $16,000.

It is worth keeping this history in mind as we enter a new period of sports activism. Some things have changed, of course; most notably, athletic compensation has increased dramatically. Today, the average football salary is $2.1 million and the average basketball salary $6.2 million. Baseball falls in the middle at $4.4 million. Los Angeles Dodgers star pitcher Clayton Kershaw, with his salary of $32 million, earns even after adjusting for inflation more than 300 times this year what Oakland Athletics ace Vida Blue was paid 46 years ago.

It is not hard to understand the resentment that can spawn from these high salaries. But one effect of high salaries is to make the drive to achieve athletic success in low-income communities of color all the more intense. As Mychal Denzel Smith wrote in The Nation a few years ago,

It’s no accident that throughout the year, the most celebrated players talk about their humble beginnings coming from poor and working-class families. It’s also no coincidence that so many of them are African American.…Why? Because this is a hustle, and so long as African Americans are disproportionately represented among the poor, they’ll also be disproportionately represented in the NFL.

The demographics of sports reflect Smith’s analysis. In the National Basketball Association (NBA), 74.4 percent of players are Black. In the NFL, the numbers are roughly similar, as 69.7 percent of players are Black.

In short, football and basketball players know Minneapolis’s Philando Castile; Sanford, Florida’s Trayvon Martin; Baltimore’s Freddie Gray; Waller County, Texas’s Sandra Bland; Cleveland’s Tamir Rice; and Staten Island’s Eric Garner. The list goes on, and if they only rarely know the victims personally, they surely know people who have faced similar circumstances—and some might even include themselves. No amount of wealth shields you from racial profiling; as a USA Today profile documents, 260 Black NFL players were subjected to police traffic stops between 2001 and 2013, compared to 28 white players.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Fueled by the rise of Black Lives Matter and growing public awareness (aided by cell phone videos of fatal shootings by police officers, which average 1,000 people a year and whose victims are disproportionately people of color and the disabled), athletes are speaking out.

This is why, for example, back in 2014, basketball players such as four-time MVP winner Lebron James (“King James” to his fans) donned “I can’t breathe” t-shirts in warm-ups to support the family of Eric Garner. Derrick Rose, a Chicago Bulls guard at the time [now playing for the Cleveland Cavaliers] tweeted, “My biggest concern is the kids. I know what they’re thinking right now. I was one of them kids. I grew up in an impoverished area.”

And the same theme resonates among professional football players. Eric Reid, a San Francisco 49ers safety who joined then-teammate Colin Kaepernick in taking a knee on the football field when the national anthem was played starting last fall, wrote this week in the New York Times, “In early 2016, I began paying attention to reports about the incredible number of unarmed black people being killed by the police. The posts on social media deeply disturbed me, but one in particular brought me to tears: the killing of Alton Sterling in my hometown Baton Rouge, La.”

We have also seen a rise of activism in other sports, such as women’s volleyball and soccer, as well as among athletes at the high school and college levels. For example, in the fall of 2015, when the University of Missouri (“Mizzou”) football team threatened to boycott their football games to support a student’s hunger strike calling the university administration to task for failing to address racial incidents, university president Tim Wolfe was forced to resign.

In all of this, it is important to recall that, particularly at the professional level, it is not easy for those who have made it out of poverty and into professional sporting success to call attention to themselves and stake out political positions on national television. After all, former San Francisco 49er quarterback Kaepernick is likely without a job because of his activism.

But when it is personal, barriers can fall. And with football in particular, the fact that your health is always at stake intensifies the personal bonds among players. Football, to state the obvious, is brutal. As sportswriter Michael Tunison notes, while players are richly compensated, the dynamics are complicated: Not only do players often come from disadvantaged backgrounds and face major health trauma on the field—including, according to a Harvard study, a significant risk of concussion (an average of five incidents per every eight games) and a per-game injury rate of 5.9 injuries a game, ten times that of hockey—but “the average NFL career is done within four years.” Then there are the longer-term health hazards. This year, the National Football League began disbursing funds from a $1 billion settlement of a class action lawsuit involving more than 20,000 former players, with maximum individual payments up to $5 million. One illness faced by former NFL players is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative brain disease resulting from brain trauma, such as that caused by concussions.

The real danger—and vulnerability—faced result in a powerful sense of solidarity. So when on Friday, President Trump, at a rally in Alabama, called for protesting NFL players to be fired and referred to anyone who protested as a “son of a bitch,” the NFL community did not take long to respond. Sports Illustrated writer Peter King underscored this point: “How would you guess strong and principled men would respond to anyone, never mind the president, calling them SOBs? In a week, five or eight protesters became in excess of 250. Three full teams—Pittsburgh (other than Army veteran Alejandro Villanueva), Seattle and Tennessee—boycotted the anthem Sunday, and other groups either knelt or sat.”

Tunison concurs:

On some level, it seems, most of those in the business of running the NFL understand this dynamic. This helps, in part, to explain why owners who have supported Trump in the past—such as Shad Khan, Robert Kraft or Dan Snyder—attempted to show solidarity with their players on Sunday.

David Zirin, a longtime critic who has written extensively on sports and politics, observed that despite the long history of political activism in sports, “nothing, literally nothing, in the history of sports and politics can compare to what happened on Sunday.”

The question, of course, is what comes next—and here we are moving into uncharted territory. We don’t know whether the protests will continue or subside. What can be said, however, is that it is on the field of play where many decisions about American identity and yes, politics, are made. In short, don’t ever let anyone persuade you that it is only a game.

This article has been altered to correct the name of Cardinals’ centerfielder Curt Flood.