March 20, 2014; Los Angeles Times

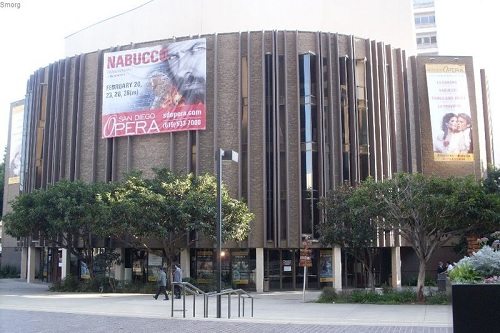

On March 20, San Diego Opera performed Verdi’s Requiem to a sold-out house, a stirring performance that Los Angeles Times music critic Mark Swed called “an angry Requiem for a senseless, premature death”—that of the opera company, which one day earlier had announced it would cease operations after its final 2014 production in April.

San Diego Opera joins a number of other major companies—New York City Opera, Opera Boston, Opera Cleveland, Baltimore Opera and San Antonio Opera—that have decided to bring the curtain down for good in recent years. Two other local companies—Lyric Opera San Diego and Opera Pacific in Orange County—have already ceased to be.

Swed, for one, can’t comprehend how San Diego’s third-largest cultural institution, a $15 million enterprise that has been ranked among the top ten opera companies in the U.S., can fold apparently “out of the blue” with a fiftieth-anniversary season already planned and, presumably, with contractual obligations stretching far beyond that. A musician in the San Diego Symphony, a key partner to San Diego Opera, told Swed the orchestra heard the news about the opera company’s demise at the same time as the public, noting that the orchestra’s 2014–15 season was in large part planned around its commitments to the opera schedule.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The San Diego Opera board voted 33-1 to cease operations, a decision board chair Karen Cohn called “heart-wrenching, but unavoidable.” General and artistic director Ian Campbell cited “an insurmountable financial hurdle going forward” and said the decision to cease operations was intended to wind down San Diego Opera “with dignity and grace” and the decision to pay down financial obligations rather than face bankruptcy.

In Europe, opera companies often receive large subsidies from the government, but here in the U.S. that subsidy tends to come from philanthropy…unless it doesn’t. In San Diego, the lack of donative revenue had been pushing ticket prices increasingly higher. It’s a familiar scenario these days in the performing arts, especially among opera companies and orchestras, where audiences traditionally skew toward the gray-of-hair and the deep-of-pockets.

As NPQ readers will remember, New York City Opera filed for bankruptcy last year after nearly 70 years, but its financial life had been far more dramatic and driven by the sometimes precipitous and erosive decisions of a string of leaders. San Diego Opera, on the other hand, boasted balanced budgets for 28 consecutive years, until fairly recently. Cohn noted that “excellent financial management” could not make up for shortfalls in ticket sales and fundraising. Earned income accounts for only about 40 percent of the company’s revenues, and it has become increasingly difficult to raise the other 60 percent. Campbell noted that some of the company’s most generous individual donors have reduced their giving as a result of the recession, while others have died in recent years.

NPQ has previously reported on opera companies looking for innovative ways to satisfy long-time opera lovers while connecting with new, often younger, audiences in an effort to ensure the art form remains relevant in the twenty-first century. Swed suggests the San Diego Opera has not kept up with these trends, noting, “Opera as an art form is changing a lot faster than this company has been.”

The curtain will rise one last time at the San Diego Opera for next month’s production of Massenet’s Don Quixote [sic]. It’s too bad the Requiem happened before that production—it might have been a better note to end on.—Eileen Cunniffe