October 24, 2018; Atlantic and Colorlines

It is well documented that the communities that endure the most damage and take the longest time to recover after hurricanes and other natural disasters are those dominated by people with lower incomes, particularly those of color. As a recent essay in the Atlantic observed,

Vulnerable people—especially racial minorities—are more likely to live in floodplains and have housing that isn’t insured or built to code. They are less likely than people with means to have reliable air conditioning. They are less likely to be able to evacuate, and they have less built-in community and familial resilience to deal with short- or long-term weather shocks than do people in wealthier, whiter communities. These differences pose existential risks to the lower classes in America.

This is in part due to the lack of investment prior to the disaster, and in part to the dearth of funds allocated afterwards.

For example, in southeast Texas, the 228 residents of Taylor Landing affected by Hurricane Harvey will receive $1.3 million in federal aid to help them relocate from destroyed homes—which works out to about $60,000 per person. It’s also among the whiter and wealthier cities. Just 15 miles east is the city of Port Arthur, where more than a third of the population is black and poor. When Harvey struck, the city was inundated. Officials estimate that almost 50,000 residents were affected by the storm—virtually the entire city. Yet Port Arthur is expected to receive just $4.1 million in aid for the owners of damaged homes or businesses. That’s about $84 per affected person.

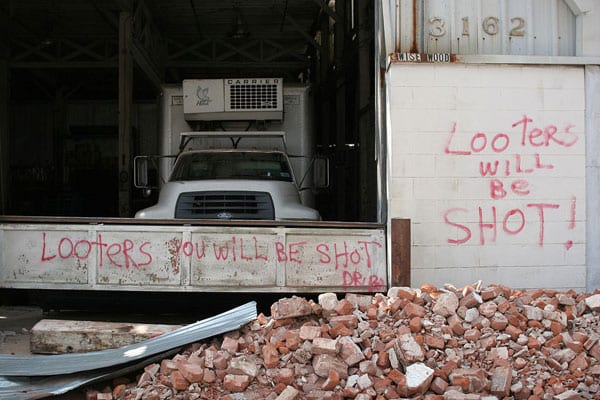

However, this disparity in fund allocation often is reinforced by the coverage of these neighborhoods by the media. Colorlines recently described this example from Wilmington, North Carolina, after Hurricane Florence hit: Hurricane survivors were reported to police for entering a flooded Family Dollar discount store and leaving with goods. According to a statement from Wilmington police, the store owners did not wish to press charges. Around the same time, however, WECT-TV reporter Chelsea Donovan arrived at the scene with a crew, broadcasting that people were “looting” and “stealing.” The video attracted thousands of online views and hundreds of comments—most reflecting racist attitudes. What was missing, however, was the context: the public housing project across the street and the lives shaped by redlining, segregation, gentrification, employment discrimination, educational inequities, and environmental injustice. As one columnist wrote, “North Carolina’s problem isn’t Florence, it’s poverty.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This wasn’t an aberration. The media’s love for documenting alleged looting by people of color is apparent in hurricane after hurricane. Remember this incident? During Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans, a photo by Associated Press photographer Dave Martin showed a young black man wading through flood water while holding a bag and a case of soda. The caption stated that he was “looting.” A second photo from Chris Graythen, taken for Getty Images, showed a similar scene, but with a white couple. Their actions were dubbed “finding.”

“People think that if you’re poor or black, you’re always trying to steal something,” retired Army Lt. Gen. Russel L. Honore told the Washington Post. “These warnings about looting validate the stereotypes that people hold about poor people. But [what you’re usually seeing] isn’t looting; it’s survival mode.”

As the Colorlines op-ed observed, “Misinformation doesn’t happen simply because journalists report false information. Misinformation also happens when they fail to represent the entirety of a community or identity of a people, and when they use information only from individuals in positions of power who consistently put forward oppressive narratives.”

There are several initiatives across the country seeking to change these patterns by encouraging more resident engagement with local media and elevating community voices and narratives. One such project is News Voices, which operates in New Jersey and North Carolina. The North Carolina branch launched in 2017 to forge better connections and break down distrust between newsrooms and community organizations like libraries, colleges, and nonprofits. It does this in part by inviting people who feel poorly served by local media to sit down with journalists and engage in a two-way conversations and joint projects such as surveys that assess how residents feel about the issues facing students, parents, businesspeople, and others.

A similar project is the Listening Post Collective, which provides journalists, newsroom leaders, and nonprofits tools and advice based on the belief that “responsible reporting begins with listening” and should “respond to people’s informational needs, reflect their lives and enable them to make informed decisions.” For example, the Listening Post in New Orleans started with an assessment of the information needs of neighborhoods left out of post-Katrina development. Partnering with WWNO, the local public radio affiliate, the project gave residents access to news via cellphone, and also allowed them to record their comments on issue-focused questions in stand-alone recording booths set up in libraries, community centers, and local businesses.

“It all starts with relationships,” write the three Colorlines authors. “Relationships require journalists to see themselves not just as members of the press but as community members. Relationships enable them to move past stereotypes and assumptions and ask the crucial questions that can illuminate what’s ailing a community.”—Pam Bailey