October 9, 2020; Nieman Lab

“To try to foretell the future without studying history is like trying to learn to read without bothering to learn the alphabet.”

Octavia Butler, “A Few Rules for Predicting the Future”

These words from prolific African American Afrofuturist author Octavia Butler ring true to the crossroads our country finds itself at today. The White House has made it clear that accurate acknowledgement of our nation’s history is not part of its vision of the future by recently denouncing federal racial bias trainings and ignoring Indigenous People Day within weeks of each other. Especially after experiencing a summer of racial reckoning, and the largest civil rights movement in American history—during a pandemic which has taken over 215,000 American lives, a majority who are from the BIPOC community—how much longer can these histories be ignored?

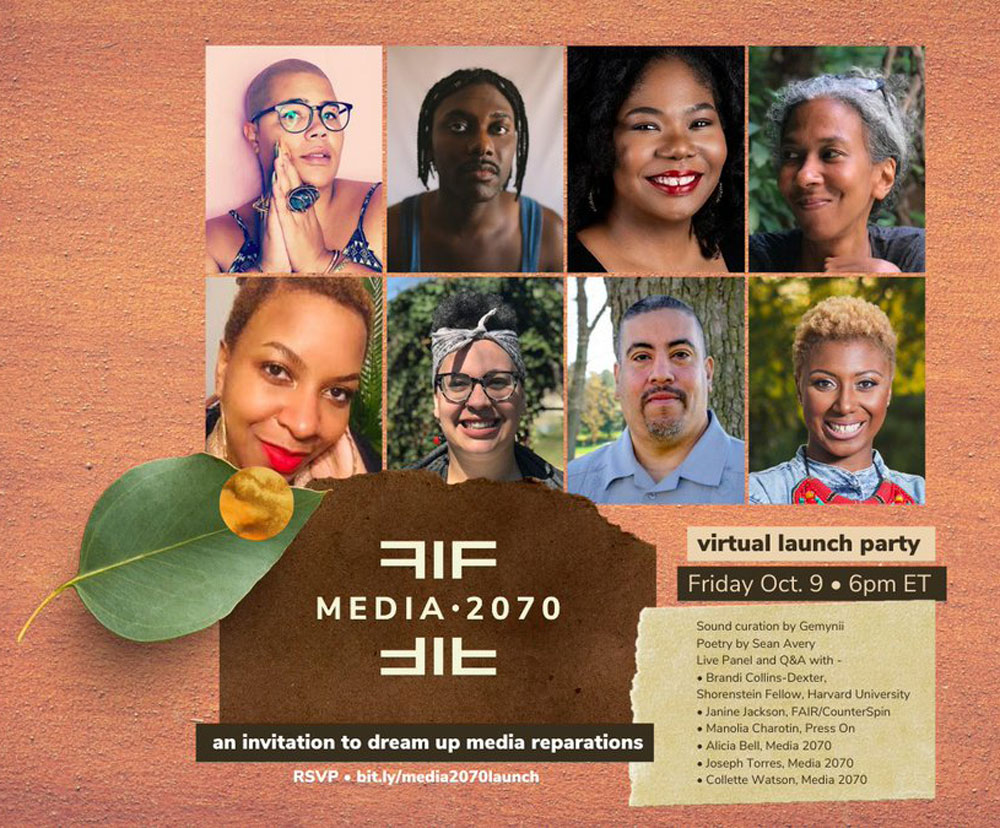

The members of the Media 2070 project aim to reconcile the harms caused by historic racist trends in the media, for the public’s benefit, and Black members within the field, by advocating for “media reparations.” The group was started by Black staff members of the media nonprofit Free Press. Co-creator Alicia Bell highlights the importance of the year 2070: “We’re honoring that every 50 years there is a reckoning,” a reference to the two major public racial review commissions 50 years apart in the early 1910s and 1960s, periods of immense racial unrest. Neither of these commissions were acted upon, yet they reflect similar findings.

The Chicago Commission of 1919 was in reaction to the Chicago Race riots, and it found that racially skewed journalism was a major factor in inciting racial violence. Fifty years later, the 1968 Kerner Commission, in response to multiple years of unrest and deaths of major Civil Rights leaders, discovered through in-depth investigation that there were structural inequities determined by race which were outright ignored or agitated by the government and media.

These separate commissions highlight the United States is stuck within a cycle of denial and inaction when it comes to reckoning with our racial divides. Media 2070 hopes to break this cycle so “the record can be set straight.” By reconciling these ignored realities in the field of media, the public can be exposed to untold experiences, and hopefully pressure institutions and policymakers to take a more active role in reconciliation. For Media 2070, “media reparations” is a way for media institutions and the government to repair harms inflicted upon the Black community.

The group recently published an in-depth essay titled “Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream up Media Reparations.” Similarly to the New York Times’ 1619 Project, the essay provides historical context on how media organizations profiteered off of chattel slavery during its early years, and upheld forms of white supremacy more recently. For example, the country’s first regularly published newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, ran slave ads within a month of its founding in 1704, with the paper’s publisher even acting as a broker. More recently in 2017, a Color of Change and Family Story study found that Black families represented 59 percent of stories focused on poverty by major outlets such as CNN and Fox, yet make up only 27 percent of the poor families in America.

The essay also provides insight on the specific harms BIPOC professionals and their communities have faced when media institutions fail to name and address problematic histories, and toxic work norms.

“For white managers in journalism, the lack of diversity is a problem to fix. For people of color, it’s a trauma to heal”—sentiments reflected from SRCCON in July 2020.

Ultimately, this work is an effort to highlight how interconnected the media is with racial justice. “To achieve full freedom and democracy,” they write, “it’s critical to change entrenched media narratives about Black people” through reconciliation and reparations.

Media 2070 uses a framework of reparations as defined by the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA):

A process of repairing, healing and restoring a people injured because of their group identity and in violation of their fundamental human rights by governments, corporations, institutions and families. Those groups that have been injured have the right to obtain from the government, corporation, institution or family responsible for the injuries that which is needed to repair and heal themselves.

Furthermore, reparations are accepted as part of the “right to remedy” within international human rights laws, with some necessary conditions: cessation, assurances and guarantees of non-repetition, restitution and repatriation, compensation, satisfaction, and rehabilitation. There are infinite ways to potentially address these harms: economic means, academic scholarships, community development, policy changes, pardons, truth-telling processes—even the creation of monuments, public spaces, and museums.

While the project is centered on the America media’s negligence regarding the Black community and experience, Media 2070 unambiguously recognizes that their media reparations framework can be used for any group consistently oppressed:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While this essay makes the argument for media reparations for Black people, any group that has been harmed by our government or by corporations has the right to demand reparations to reconcile and repair the injuries caused to their communities. Colonialism, capitalism and imperialism have been destructive forces for people of color in the United States, starting with our nation’s Indigenous communities.

Reparations have been sought after as far back as 1783, with the formerly enslaved Belinda Royall’s pension petition for her labor to the Massachusetts General Assembly. Various forms of reparations have been obtained for different communities—land and title granted to Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, the 1988 Civil Liberties Act granting monetary reparations to Japanese Americans interned during WWII, treaties for Alaska Natives and American Indians. Yet there’s been little in regard to the long-lasting effects from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and white supremacy.

In the wake of the racial reckoning sparked by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and compounding Covid-19 effects, many are asking: Has the time finally come for reparations? The call has been renewed for Congress to pass H.R. 40—the “Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-American Act.” California’s state senate passed Assembly Bill 3121, which begins the process of investigating, recommending, and acting with legislation and compensation.

So, what would media reparations entail? One of the first steps media institutions and leaders could take is openly acknowledging their role in the historical harm their institutions have caused and reflect a willingness to work with the community to make sure those harms are not repeated. This aligns with research on community and intergenerational trauma, which highlights the importance of acknowledgement and naming as integral processes of healing, whether on an individual or societal level.

This could take the form of engaging in critical reflection—internally as an individual, or on an institution’s history, organizational culture, staffing, and leadership. Truth-telling processes, such as uncovering or rediscovering stories of harm caused by the news media that have gone to the wayside of history, are important as well. Many institutions have already begun this, often in reaction to BIPOC staff pressure, leading to published apologies for institutional problematic roots, such as the Los Angeles Times’ “Our reckoning with racism” editorial.

Recognition is only part of the process, though; in some cases, leadership transitioned or resigned. Notable cases from the L.A. Times, the New York Times, and the Philadelphia Inquirer were connected to published pieces that were openly problematic, insensitive, or reflective of longstanding toxic practices. The creators of Media 2070 are not calling for a massive transition of all white leadership, nor is this work to be undertaken entirely by the BIPOC staff and community. They highlight the importance of gathering together to build relationships, figure out new media structures, make reparation a reality, and craft a stronger future.

“There are a lot of skills and experiences that white leaders can contribute to building the future of media. And there is an abundance of skill and vision and strategy amongst Black and Indigenous media leadership,” Media 2070 leadership said to the Journalism Institute. “Many of the skills and experiences that white leaders have can be used in support or mentorship roles as we figure out how to practice multiracial racial justice.”

These ideals ultimately reflect creating a new media model that aims to dismantle white racial hierarchy, and uplift BIPOC voices:

We’ve only ever had a media system that’s been abundant with white leadership and that system has never served all of us, so now is as good a time as any to figure out what innovation there is to glean—economically and otherwise—from an abundance of Black and Indigenous news media leadership.

To do so, Media 2070 envisions intervention from multiple levels, including the federal government. They urge legislators and institutions like the FCC to play a more active role by undoing harmful policies that promote anti-Black racism, providing equitable funding for local journalism and BIPOC media institutions, and supporting legislation and financial support that would go towards reconciliation and repair racial wounds within media.

Even if all of these acknowledgements are vocalized and policies enacted, however, without participation and input from the BIPOC communities more broadly, there will not be a firm foundation for the reparations to truly be an effective means of reconciliation.

“To merely focus on finance is an empty gesture and betrays a lack of understanding of the depth of the unaddressed moral issues that continue to haunt this nation,” US Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) and advocate for H.R 40, reflects. “Though the civil rights movement challenged many of the most racist practices and structures that subjugated the African-American community, it was not followed by a commitment to truth and reconciliation. For that reason, the legacy of racial inequality has persisted and left the nation vulnerable to a range of problems that continue to yield division, racial disparities, and injustice.”—Chris Cannito