Some years ago, we were engaged by a national foundation with a criminal justice reform agenda. They paid our fee in order for us to assist governors who were looking for corrections leaders. The governor was our client. Our obligation to the foundation was to provide governors with a comprehensive search process. The foundation’s hope was that stronger and more effective leadership would result.

Over a period of seven years, we recruited 18 state cabinet officers—more than a third of all the leaders in the country—distributed over every region of the US. Taken as a whole, the project was a great success.

The issues that shape these jobs are incredibly difficult. Public safety, race, mental health and drug addiction, an odd mix of NIMBY and competition for prisons as a stimulus for jobs and the local economy, challenging workforce issues and “getting tough on crime” add up to a very complex assignment.

Due diligence also revealed a striking difference between the role of most corrections secretaries and that of other major cabinet officers. Those who lead most other government systems—environment, transportation, public health, economic development, human services—are typically subject matter experts. They have run organizations and they understand the operational and practical challenges. As a cabinet secretary, their role is often to use this knowledge and professional credibility to advocate for innovations and to influence policy makers and the public. Their agenda must be negotiated with a governor’s office, but most often it is the cabinet secretary who drives that process.

We saw a different construct with corrections secretaries. Governors usually view corrections as a third rail. Their tendency is to be risk averse, to maintain a stable system and invest their political capital in other, more promising, areas. Traditionally, these positions were filled by institutional administrators—wardens who had worked their way up the system. Their orientation was toward institutional management and command and control. The common division of duties was for corrections administrators to focus on operations, with legislative relations, policy, and media activities closely controlled by the governor’s team.

For us, this raised a chicken-and-egg question. Was the candidate field dominated by operationally oriented managers, requiring governor’s staffs to be more active in controlling policy and strategy, or did the risk averse and controlling approach of governors’ staffs screen out more strategically oriented candidates?

It is in the nature of our approach to beg the question when preparing for a search. Who sets policy? What are the strategic, policy, and political goals for the chief executive we are seeking? What authority rests with this person, and what remains with the governor’s office? Are we looking for a general manager or a more typical cabinet officer? The answers to these types of questions shape a search.

For the most part, we found governors receptive to these questions. They understood the value of cabinet officers who were capable of strategic leadership and they had a system in place to balance that type of leadership in a cabinet management process. It was not a great leap to adapt this approach to a corrections leader if candidates with these broader skills were available. (Though some governors’ staff members had a different view, as you might guess.)

From a recruiting perspective, the begging of the question was the answer. As we signaled that our client was interested in corrections professionals who had skills in strategic leadership, public policy, legislative relations and the like, they were quick to appear. Over the course of these 18 searches, we saw a new generation of leaders. Where their predecessors had mostly come up through the ranks, the new leaders tended to have a more diverse background. Usually they had institutional experience, but over time they had moved more laterally—community corrections, jail administration, planning, policy, budgeting. They were solid correctional professionals, but their portfolio and their perspectives were broader and more strategic.

This was (and still is) a terrifically difficult field. Sentencing policy was exploding the prison population. And while most of these talented candidates saw the madness of such policies, and a few were successful at advocating for more rational sentencing policies in individual state jurisdictions, this was a tidal wave that washed over everyone. However, what I also saw was a generation of new leaders who made the case for a more nuanced and strategic approach. They promoted substantive inmate classification systems, mental health and drug treatment, education, and step down levels of community corrections and re-entry programs. They were “traditional” cabinet officers like those described above—able to use their knowledge and professional credibility to influence policy makers and the public and to advocate for innovation and improvements.

In my view, this is better. There is a benefit to checks and balances in the structuring of these positions. A governor’s staff and, often, outsiders like academics, advisory boards, task forces, and consultants help the governor evaluate and manage a cabinet officer’s activities. But the balance is far more effective when the counterpoint is a strong cabinet secretary who has a strategic agenda. When the cabinet officer is a manager, you miss the critical connection between strategy and implementation. The alternative is, in effect, for (the governor’s) staff to be shaping policies that have operational implications—never a good idea.

I believe we made a very real contribution to this field. By “begging the questions” and facilitating a robust and open conversation about the circumstances that truly define these positions, we brought our clients to a far more thoughtful exploration of the issues and forged very effective relationships among the parties. I could cite many positive examples, but to make the point, I will describe what was perhaps the most disappointing outcome I have seen in my entire career. Happily, it was a rare occurrence.

After so many searches in this field, we had arrived at a point where we knew most of the leaders and had placed the most talented among them. We were faced with the prospect of recruiting away people we had already placed, the kind of thing that gives recruiters a bad name. So we decided to opt out of the program and focus on a more diverse clientele.

One of the last assignments we took in this field was to recruit the administrator of one of the largest prison systems in the country. It is no exaggeration to say that this was and remains a big business in this state. Our client was an oversight board, appointed by the governor. The system was embroiled in a number of class action suits, with the real possibility of being taken into federal receivership. Our client’s hope was that we could recruit a transformational leader who could bring about change from the inside.

Our client board was composed of members with a rich mix of ideologies and experience: reformers, victim’s advocates, corrections experts, and—the majority—“lock ’em-up” hyper-conservatives. Parts of this search were exhilarating. Removed from the public posturing by the necessarily private element of a personnel process, we found the board willing to entertain a more nuanced dialogue about strategy and policy. The promise of such a dialogue attracted a stellar group of candidates. The consistent theme that emerged from top candidates, that education, job training, mental health services, addiction treatment, and, ultimately, sentencing reform might be a better means for protecting public safety than warehousing and farm labor, was something hardliners had dismissed in every other forum. In this closed setting, it was more possible to weigh and debate these ideas, tease out the rhetoric about how such reforms could benefit public safety and punish bad guys—and make the point that this approach was more likely to keep the system out of receivership.

Very long story short, we came to a point where we had two final candidates. One was an outsider. He was a tremendous candidate. He had impressive corrections leadership experience in another large, neighboring state. He was an inspirational leader. He had the management chops and the gravitas, and the communications and political skills needed to drive a reform agenda. There was nothing wimpy about him, including his ability to make the case for how his approach would positively impact public safety.

The other candidate was an insider, who had been clear that he was for a status quo approach.

Our search came to a head in a conference room at the Four Seasons. The Board met for a final interview with the two candidates. Just the Board, myself, and then each candidate, one after the other, were in the room.

The outside candidate was tremendous. He took in every concern about what change would mean. He articulated a thoughtful approach, and made the case for how he would carefully shape and implement this agenda in close collaboration with the Board, the governor and the legislative leadership.

The inside candidate was far less impressive, especially in contrast to the outsider.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That afternoon represented the best of what we had accomplished over those 18 searches. A genuine exchange of ideas, a deeply rational logic, a mutual respect for the ideologies that drive these systems and a savvy political strategy emerged from the conversation with the outsider. It was not just a strong presentation, it was a dialogue, and it started to move this diverse committee towards a set of common goals.

The discussion that followed the interviews was brief. The decision was clearly going to be for the outsider.

Before the Board was to vote, one member, who had been largely quiet through the entire process, asked us to pause for just a moment while he left the room. He stepped out, and came back in about five minutes later—with the Lieutenant Governor.

This is a “weak governor” state. The Lieutenant Governor controls the Senate, and arguably is the strongest politician in the state. He looked around the room and pointed at me.

“Who is that?”

“Our search consultant,” said the Chairman.

“He needs to leave,” said the Lt. Governor, and the Chairman asked me to do so.

I waited in the hallway. I couldn’t hear what was being said, but I did hear shouting. About 45 minutes later, the Lt. Governor came out. He walked by without acknowledging me. The Chairman then stepped out and asked me to come back in. The room stunk of sweat and fear—like a high school locker room. As I scanned the room, I saw long faces and some tear-reddened eyes.

The Chairman said, “Ted, we have already voted. We are hiring (the inside candidate).” Someone actually whimpered when he said it.

All I could muster was, “It is the Board’s decision, but in all honesty I am surprised and disappointed. We found the candidate you all hoped for at the start. But best of luck to you all, and goodbye.”

I turned to leave and a few Board members called out to me. “Please walk with us to the press conference. Some of us have learned a tremendous amount from this process. And regardless of this result, we will continue to apply that learning. We value what you have done and we would like to honor that by walking into the press conference with you.”

Again, this is a big business. A press conference had been planned at the other end of the hotel. A large ballroom was packed with reporters and interested parties.

Using the service corridor, the Board and I walked towards the ballroom. It was a bit confusing, because in the corridor the rooms were marked by numbers, not names, so we weren’t sure which was the correct door.

About halfway down the corridor, we came to a large door that we thought was the one. We opened it, and found all of us reflected in a wall-to-ceiling mirror, in an empty ballroom.

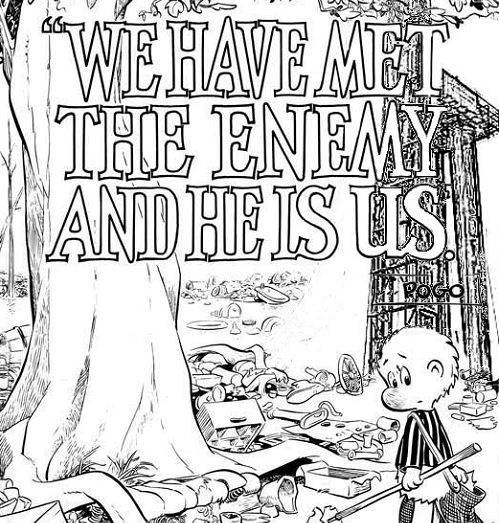

In that brief moment, with all of us framed in that mirror, I remembered Pogo, and said, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

More sobs, and the Chairman spoke up. “Ted, we have come far enough with you. We will take it from here.”

And that was that.

I recognize that we came so close to introducing change and reform that we unleashed an extraordinary intervention. All stops were pulled out to protect some very powerful and entrenched interests. I suppose that, in a sense, that is a tribute to the power of the process. But as I said above, I think of this as a sad and disappointing outcome.

The search opened the door to effective leadership, but they let the wrong person walk in.

A few years later the insider who got that job was indicted for fraud and removed from his position.