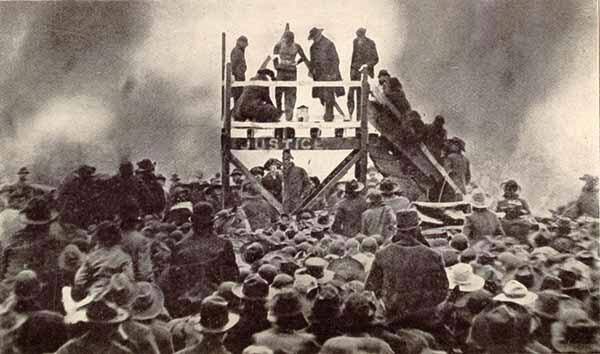

With its recent opening, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama spotlights the nation’s history of violent racism. Telling the stories of the men, women, and children who were killed because they were black, the Memorial asks us to remember and to consider how we have allowed this brutality to go on, decade after decade, and have looked the other way.

The Memorial is the project of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit organization “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.”

Bryan Stevenson, founder of the EJI, spoke to the New York Times about the motivation for creating the Memorial: “I’m not interested in talking about America’s history because I want to punish America. I want to liberate America.”

According to the Times,

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Mr. Stevenson, whose great-grandparents were slaves in Virginia, has written about “just mercy,” the belief that those who have committed serious wrongs should be allowed a chance at redemption. It is a conviction he has spent a career arguing for on behalf of clients, and he believes it is true even for the white America whose brutality is chronicled by the memorial.

The power of the Memorial has been seen on the pages of the Montgomery Advertiser, which has begun a soul-searching look back at how its coverage whitewashed case after case of lynching. In a powerful editorial, the Advertiser declared, “We were wrong.”

The Montgomery Advertiser recognizes its own shameful place in the history of these dastardly, murderous deeds…part of our responsibility as the press is to explore who we are, how we live together and analyze what impacts us. We are supposed to hold people accountable for their wrongs, and not with a wink and a nod. We went along with the 19th- and early 20th-century lies that African Americans were inferior. We propagated a world view rooted in racism and the sickening myth of racial superiority.

Alongside their editorial, the Advertiser has begun a series of in-depth retrospective looks at the details of how it covered numerous lynchings. The paper reflected the prevalent view of their white readership: Black people were criminals, and those who were brutalized deserved to be killed.

In explaining the Advertiser’s motivation for publicly sharing their own tacit support of racial violence, Bro Krift, the paper’s editor, told the Times, “I think the takeaway for us is that we need to be conscious of the words that we choose and how we characterize people in our newspaper. One-hundred fifty years from now, there might be a historian that looks back on how we covered these events and Montgomery in 2018.”—Martin Levine