November 10, 2019; Lansing State Journal

Housing advocates in Michigan continue to raise concerns over a federal affordable housing program. These concerns echo similar sentiments across the country as municipalities continue to struggle to meet the demand for quality affordable housing.

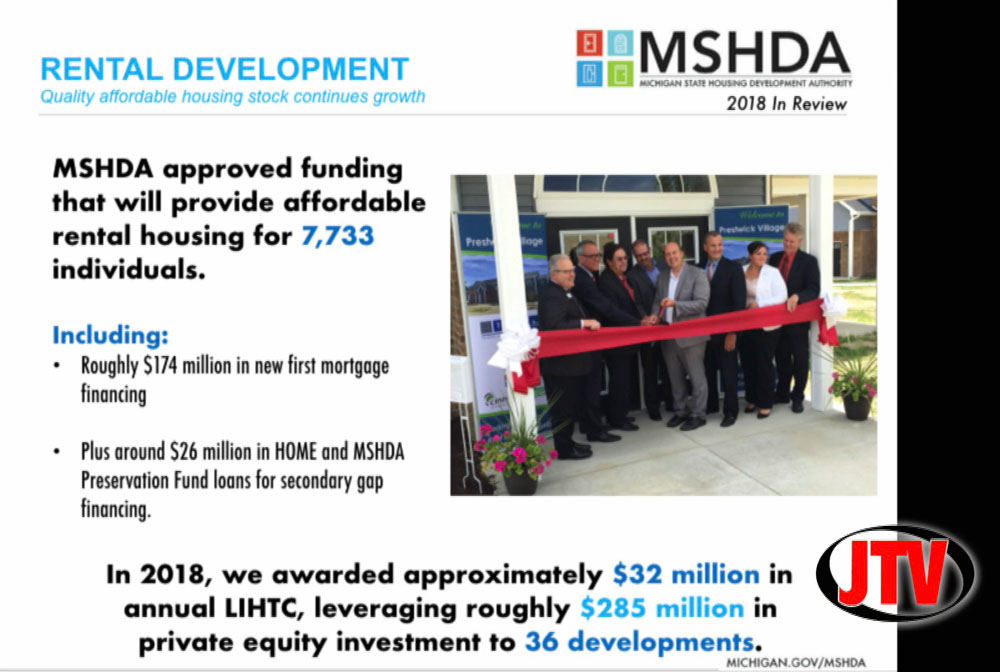

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) is a federal program that is administered through state housing agencies—in this case, the Michigan State Housing Development Association. The program is administered through a detailed scoring system called the Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP). Each state has its own scoring system. Developers who seek the federal tax credits apply, and the state distributes the credits based on the applicants’ scores.

The Lansing State Journal reports that Michigan’s scoring system pools together applications from all cities with over 50,000 residents. This means that Lansing, home to 118,500, is competing against cities like Detroit, with a population of 672,700.

Rawley Van Fossen, executive director of Capital Area Housing Partnership, based in Lansing, argues that Lansing faces an unfair disadvantage. In a letter to the state housing department, Van Fossen provides a variety of options, such as creating an additional category for cities with 50,000 to 200,000 residents, prioritizing nonprofit development projects submitted by community housing development organizations, increasing mixed-income and tenant-owned developments, and allowing nonprofit organizations to join the committees that determine the scoring system.

The LIHTC was created as a result of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The federal program provides tax credits to investors—often banks—in order to incentivize investments in affordable housing. By purchasing tax credits, banks reduce the money they owe the federal government. In turn, the dollars invested in the projects can support both the construction of new properties and the renovation of existing buildings. Even though housing production remains far short of what is needed, as a report from the Urban Institute observes, presently LIHTC is “the only major [federal] funding source for producing and preserving affordable rental housing.”

The Urban Institute notes that 45,905 projects and 2.97 million units have been created through the program between 1987 and 2015. Projects created through LIHTC are complex and include a variety of actors, such as federal and state governments, investors, and real estate and tax specialists. The report explains that the “basic requirements of the LIHTC program focus on how affordable the rents must be and how long those rents must remain affordable.” LIHTC projects are required to meet affordability requirements for at least 30 years.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Clearly, more resources are needed for Lansing, Detroit, and elsewhere. The battle in Michigan is a symptom of a broader sickness in the system. A 2018 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition found that the “US has a shortage of seven million rental homes affordable and available to extremely low-income renters, whose household incomes are at or below the poverty guideline or 30 percent of their area median income.” In other words, for LIHTC to fully meet the housing need would have required the construction of 10 million, not three million, units.

The Urban Institute report outlines some other challenges too. Among these are the fact that units built are not required to be permanently affordable, the program does not intentionally serve the lowest-income households, and the tax-credit mechanism itself leads to inefficiency, with a complex process driving up costs due to the many actors involved. The report contends that other strategies, like housing vouchers, are cheaper over time than LIHTC. Others argue that the program may even reinforce segregation by placing many LIHTC units in high-poverty areas.

As Luke Forrest of the Community Economic Development Association of Michigan observes, the fundamental problem is a mismatch of resources and demand, a problem that exists in big cities, mid-sized cities, and rural areas. Forrest adds, “There just aren’t enough funding mechanisms to support affordable housing around the state, so you have Lansing fighting against Detroit and all these other communities for limited resources, so everyone ends up unhappy.”

In an interview about her newly released book, Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership, scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor summarizes the problem bluntly:

The reason why we continue to see the same kinds of problems whether it’s residential segregation, whether it is the hostility of mortgage lenders, these kinds of predatory preying on black people is not an industry stuck in its ways. It’s not just an inability to move ahead. It’s because these practices have proven themselves to be profitable over and over again, that this is essentially housing under capitalism…The reason for this is because of the US government’s continued reliance on the private sector to produce housing for low-income and working-class people. And affordable housing for working class people and housing for poor people is not profitable. That’s why it never gets built in sufficient numbers to actually satisfy the need. And so, this is why we continue to see the same iterations of the same problems just in different places in different times. But it’s really the same discussion that we’re continuing to have and that is the destructive role of the private sector when it comes to actually satisfying the housing needs of poor and working-class people in this country.

What is clear is that the US will have to support new approaches and strategies to make housing affordable. Alternatives such as community land trusts, which remain permanently affordable, and limited equity housing co-ops, which provide equity back to their residents, are examples of more sustainable options. These strategies also starkly contrast with the LIHTC program in that residents are involved in the process.

Meanwhile, the country proceeds on the opposite path. Industry sources estimate that the 2017 federal tax bill, by lowering corporate tax rates, will reduce housing provided through LIHTC by nearly 235,000 homes over a 10-year period.—Benjamin Martinez