August 4, 2020; New York Times

Despite the justified fear that COVID-19 would render the newly energized ballot initiative strategy moot, progressives secured a big win in red state Missouri on Tuesday, overriding the legislature’s and the governor’s persistent refusal to expand Medicaid. It is the sixth state to do so.

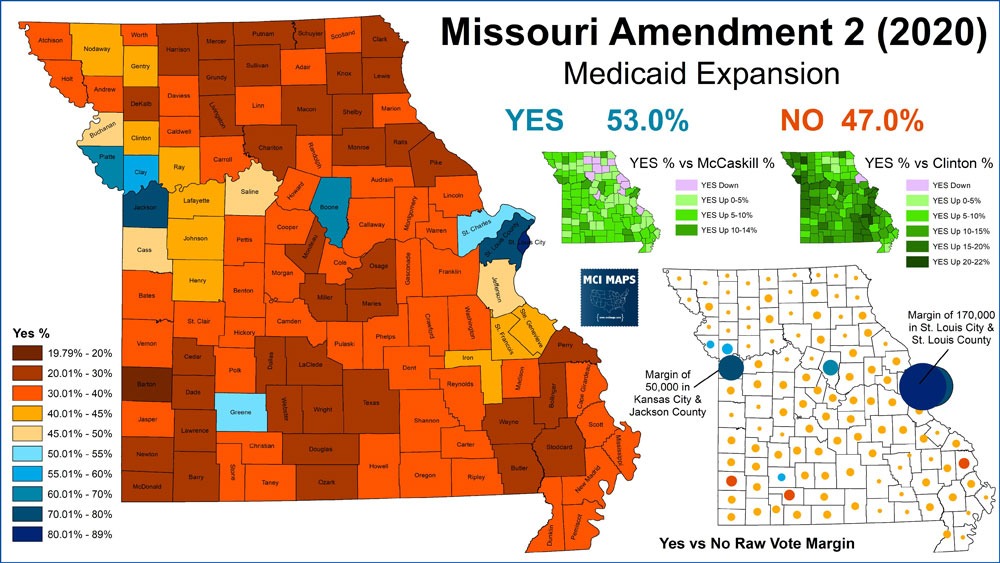

The Missouri vote, 53 percent “yes” to 47 percent “no,” followed a now-familiar pattern with urban voters overwhelmingly supporting Medicaid expansion and rural voters decisively rejecting it. But observers think COVID-19 has diluted this pattern—a bit—with “surprising” rural support in some precincts:

“The biggest visibility piece we have here in the rural areas is, people drive by a hospital and see a ‘Closed’ sign on it,” says Erich Arvidson, a campaign leader, banker, and former congressional candidate. “The COVID-19 crisis resonated with people on a basic level.”

Indeed, 10 rural hospitals have closed in Missouri in the past five years, and the state has faced one of the sharpest increases in daily COVID cases in the past weeks, almost three times more than a month ago. Although the state has one of the most restrictive Medicaid programs in the country, its program enrollment has risen nearly nine percent between February and May—among the largest increases in the nation.

How did this ballot initiative succeed in COVID-era Missouri?

Early start. COVID did have its impact on Missouri’s ballot initiative, forcing the campaign to go virtual in late March and suspend all public events. But organizers had made a strong start before the pandemic took hold, launching their campaign in September 2019 and meeting the early May 2020 deadline of 160,000 signatures.

Powerful supporters. The campaign brought some unlikely players together to support the initiative, including the Missouri Chamber of Commerce (typically a solid supporter of the Republican governor, but who called the proposal a “pro jobs measure that will help fuel economic growth throughout our state”), as well as expected endorsements from such major nonprofits as the AFL-CIO, NAACP, AARP, the Missouri Hospital Association, and Planned Parenthood. The Chamber was persuaded by economic studies that show that stable health insurance saves jobs. In Missouri, Medicaid expansion is projected to create more than 16,000 jobs annually over its first five years and expand Missouri’s economic output by $2.5 billion a year.

Opponents included the Missouri Farm Bureau, Americans for Prosperity, and Missouri Right to Life. Proponents raised $10.1 million to support the campaign; opponents only $111,834. (No national hospital chains or associations backed the campaign, however.)

A savvy national partner. One key player wasn’t from the “Show Me” state. The Fairness Project, a DC-based national nonprofit with a staff of 13, more than 6,000 online donors, and a budget of roughly $6 million was central to the successful campaign in Missouri and in the five other states with recent and successful Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives. Launched in 2015 with $5 million from the union that represents California’s health care workers (SEIU-UHW), the Fairness Project works with local advocates to build professional campaign websites, aggressively use social media, and ensure that polling is done rigorously, as well as riding shotgun with state partners during the campaign. Its money helps, too. In the 2018 Utah ballot initiative, this national organization contributed $3.5 million out of the $3.8 million raised; in Nebraska, $1.69 out of $2.86 million garnered; and in Maine, $1 million out of the $2.67 million secured, dwarfing the opponents’ fundraising efforts.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“Most ballot initiative campaigns are underfunded and under-resourced, especially at the beginning,” says Fairness Project’s executive director Jonathan Schleifer. “We make early risky investments in incubation work, research, coalition building, grassroots/grasstops organizing, and signature collection.”

The Fairness Project has also played a key role in winning ballot initiatives to mandate minimum wage increases and mandated paid leave in recent years.

Learning from other states. After ballot initiatives are approved, opposing governors often delay, modify, or refuse to execute the voter’s wishes. In Maine, Governor Paul LePage threatened that he “would go to jail” rather than expand Medicaid, and it took the election of a new governor three years later to implement the 2016 voter-approved ballot initiative to expand Medicaid there. In Utah, the state agency in charge added the caveat that Medicaid enrollees had to work, search for work, or volunteer to get covered—a provision not in the original ballot. And in Missouri, before the initiative was even decided, the governor moved the date of the vote from November to August, when turnout is predictably low.

So, when the time came for Oklahoma and Missouri to launch their Medicaid expansion campaigns in 2020, proponents launched a new strategy, seeking constitutional amendments that could only be altered by another statewide referendum. This worked in Missouri, despite the requirement for significantly more signatures to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot—160,199 instead of 100,126.

What’s next?

In Missouri, a top Democrat on its House Budget Committee predicts Republicans will try to stymie of Medicaid expansion by underfunding it. But when it does move forward, coverage will be extended to 217.000 residents.

There are 12 remaining states that have not expanded Medicaid, but only four permit referenda: Wyoming, South Dakota, Mississippi…and Florida, with 1.25 million potential Medicaid enrollees.

But the fate of the ballot initiative in these states while COVID-19 endures is not clear. Fourteen states have suspended 2020 initiative campaigns. Nationally, the number of certified statewide ballot initiatives was just 111, down from 167 in 2018 and 162 in 2016. And the likelihood of states permitting signatures to be gathered electronically is minimal. In April, Massachusetts became the first and only state allowing campaigns to collect electronic signatures for the 2020 ballot. No one else has followed suit.

What’s at stake? First of all, issues that matter to progressives. In Arizona, initiatives to raise the minimum wage for health care workers and increase the transparency of campaign financing was suspended. In North Dakota, a campaign to legalize marijuana is punting until next year, as has San Francisco’s sales tax to fund public transit, and Seattle’s effort to revive a business tax to fund green affordable housing.

Second, for some advocates, the vitality of our democratic process is at stake. “Ballots are an opportunity to put a question, in its undiluted form, in front of millions of people,” says Dave Regan, president of United Healthcare Workers West. “As opposed to traditional legislative work, where things get watered down to get out of committee, you end up with what you actually want when you use the ballot.”

But celebration is in order, and let’s applaud the recent vote in Missouri and the presence of a savvy and supportive national organization, the Fairness Project, for keeping this vital tool alive and (sometimes) kicking.—Debby Warren