This article, first published on July 9, 2019, comes from the summer 2019 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly as part of a cluster of articles on the subject of accountability to stakeholders. It includes excerpts from “Lessons from Citizen Journalism—the Promise of Citizen Philanthropy,” an essay in the report Global Media Philanthropy: What Funders Need to Know About Data, Trends and Pressing Issues Facing the Field, published by Media Impact Funders in March 2019.1

It was one of those moments that crystallized what words often cannot.

Several years ago, a group of nonprofit and philanthropic executives met to explore ways to strengthen civic participation. They were joined by two practitioners who issued a challenge: Go beyond defining success as increased voting and volunteering numbers to creating civic cultures in which civic engagement is part of everyday life. That means seeing civic engagement as less a set of tactics and more a process through which people have opportunities to come together, identify common priorities, and take action to address them in ways they see as appropriate.

Two things, they said, are critical. First, a cross section of the community participates—not just those who are more inclined to do so. And second, community participants are seen as equal partners with—rather than constituents of or advisors to—traditional power brokers. That means ensuring everyone has the chance to be involved—not just experts but also “real people,” whose lived experience is equally valuable when it comes to decisions affecting their lives.

The CEO of one of the country’s largest grantmaking organizations raised a hand. “We already go into the communities we support. We ask them what they see as priorities, and they tell us. But let’s be honest. We’ll listen, but ultimately we’ll decide what we’re going to do there, because we know what to do, can get it done faster, and do it more efficiently. So what’s the incentive?”

Silence and seat squirming ensued. Then, another colleague spoke up: “Because the world is changing, and if philanthropy wants to have the impact it says it wants, it has to change with it.”

Those changes have become a reality.

Among them are growing distrust in—and demand for accountability from—traditional institutions; the democratization of fields and practices that were once largely the purview of experts and gatekeepers; and technological innovations that give people the chance to connect, collaborate, and crowdsource solutions to problems in spaces that are more transparent, and virtual.

These trends reflect a backlash against the “establishment” occurring in politics, higher education, the media, and other fields in which elite interests are perceived to have drowned out the concerns of ordinary people. Americans of all stripes and political persuasions have come to believe they have little say in guiding public decisions and improving the health and well-being of their communities.

Philanthropy hasn’t been immune to these trends. Faced with growing public critique, funders are taking a closer look at how they can be more accountable and transparent. Fieldwise, conversations about equity, diversity, community engagement, and inclusivity have snowballed.

One of the most visible indicators of this shift has been a movement to encourage donors to solicit feedback from—and really listen to—their grantees, beneficiaries, and other stakeholders. There’s no question that this is a positive and long-overdue shift for a field in which there’s a lot of talk about addressing the power dynamics rife in philanthropy, but comparatively less commitment to walking the talk.

But are listening and feedback enough to upend the deeply entrenched power imbalances that have been a hallmark of institutional philanthropy?

Some aren’t so sure. They say that giving people opportunities to provide feedback is necessary but insufficient for breaking down power imbalances, especially if the people asking for that feedback are still making the ultimate decisions about the lives of the people providing it. The result is a loop back to the top-down, expert-driven system that’s ingrained in institutional philanthropy.

This conundrum isn’t exclusive to philanthropy; it has been a long-standing issue across other fields that have participation at their core, such as community organizing, community development, public problem solving, and deliberative democracy. For decades, practitioners and scholars in those fields have grappled with how to engage ordinary people in decision making that goes beyond asking them for feedback and/or input to seeing them as actors in all facets of planning, implementing, assessing, and developing efforts to strengthen communities.

What can philanthropy learn from their efforts? A lot. A review of this work, in fact, surfaces knowledge that’s remarkably consistent across these different fields:

- Decision-making and problem-solving processes need to involve the people most affected by an issue or problem because they have firsthand knowledge and experience.

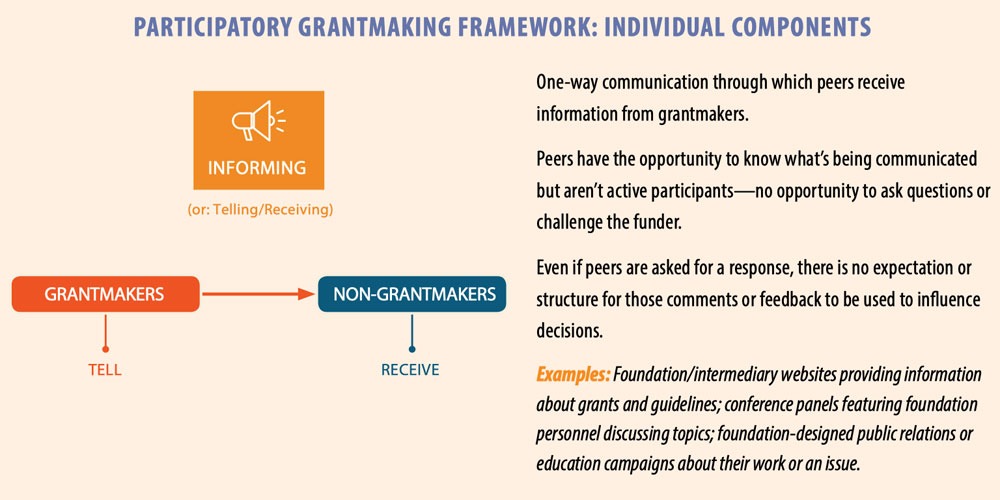

- Authentic participation involves two-way or multidirectional communication, rather than didactic approaches that inform or “educate” people with no venue for their feedback, input, or active engagement.

- Collaborative problem solving that involves the equitable participation of diverse people, voices, ideas, and information can lead to better outcomes and decisions.

- Community organizations and government need to work with—rather than for—the public.

- Experts and professionals aren’t necessarily the drivers of problem solving or decision making but are partners with the public in those processes.

- Transparency—about decision-making processes, who is involved, what decisions are made, and how they will be implemented—is essential to authentic participation.2

Those in philanthropy who have experimented with participatory approaches have found similarly. One example is CFLeads, a network of community foundations established to expand community foundations’ role from asset builders and grantmakers to “community leadership”—an approach aimed at strengthening neighborhoods through more proactive community engagement.

Over time, some community foundations doing this work found that an element critical to impact was missing: the active, meaningful participation by the people who live in the neighborhoods and whose lives are most affected by the policies, systems, and structures targeted for change. These organizations began undertaking efforts that went beyond asking residents for feedback to working with them to identify community opportunities, challenges, and options, and then decide together what should be done. According to Engaging Residents: A New Call to Action for Community Foundations—authored by CFLeads’ Cultivating Community Engagement Panel, a diverse group of thirty-four individuals from philanthropy, academia, government, and neighborhood and community organizations that work closely with residents—the “result has been more involved communities and a high level of satisfaction with both the process and the outcome of public decision-making.”3

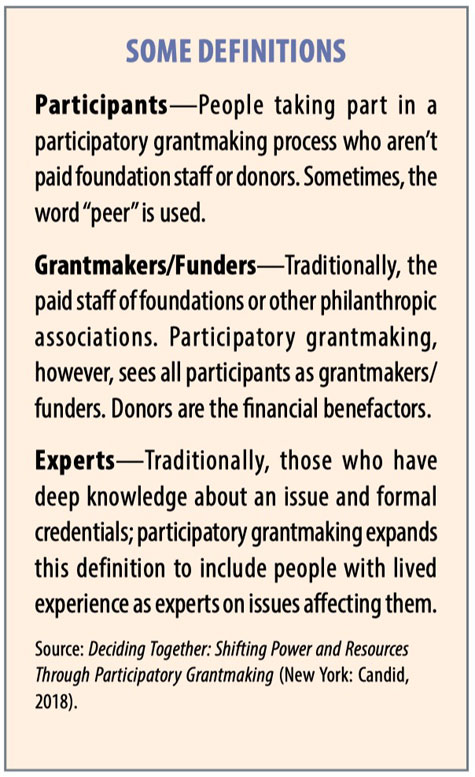

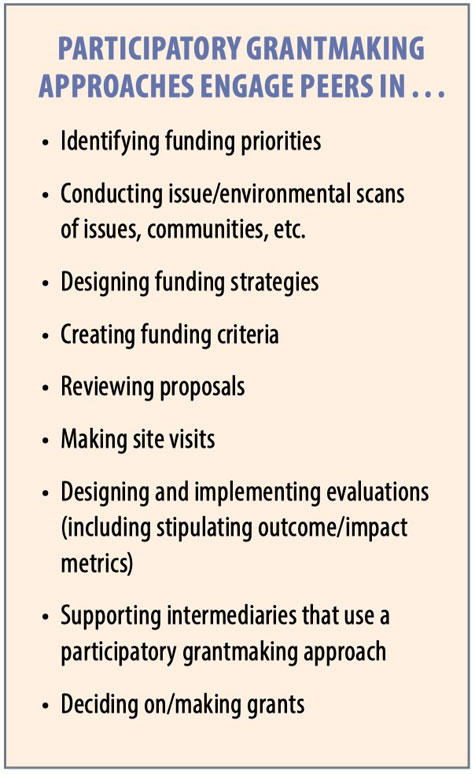

A growing number of other funders are also testing and using participatory approaches to philanthropy that upend how resources are allocated, by whom, and to what end. Specifically, they’re moving away from independently deciding what gets done to working with non-grantmakers—or “peers”—in all parts of the grantmaking process. Some are even partnering with them in making grant decisions.

In short, participation is becoming a lever to disrupt and democratize philanthropy. And it’s gaining traction. In 2018, Inside Philanthropy named participatory grantmaking the “most promising sector reform effort.”4 Earlier this year, the World Economic Forum cited the democratization of philanthropy—through efforts like participatory grantmaking—as one of six key trends in the field.5

What Is Participatory Grantmaking?6

Some see participatory grantmaking as one of many types of participatory philanthropy. Others see it as distinct, because it moves decision making about money to the people most affected by the issues donors are trying to address.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

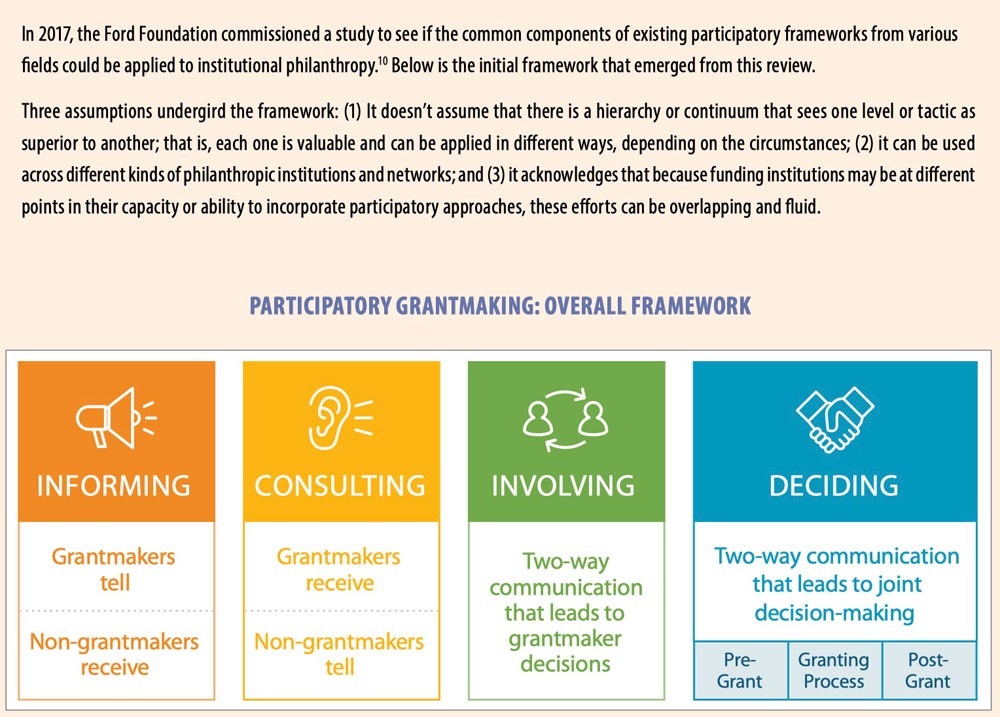

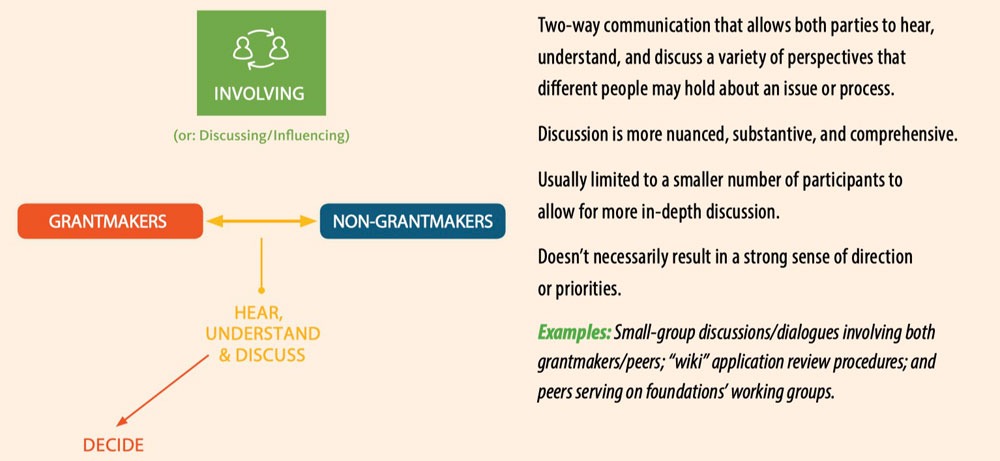

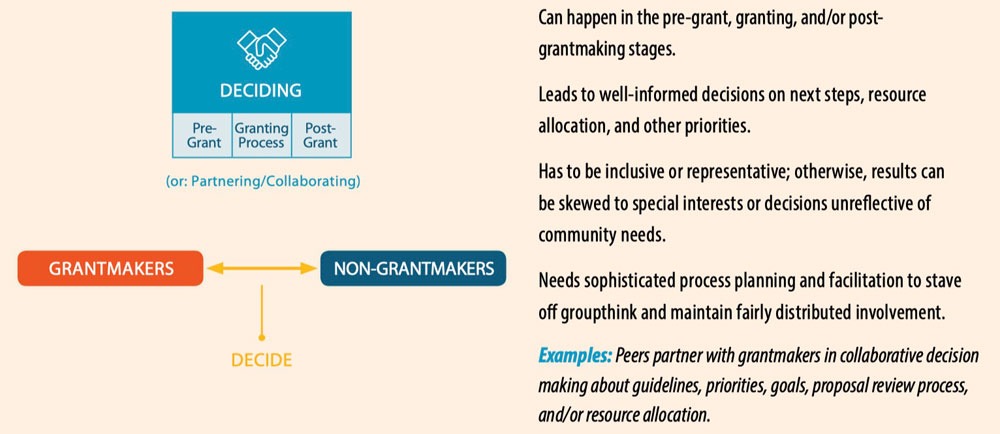

Generally, participatory philanthropy can include a range of activities (see graphics at the bottom), all of which can be—and are being—used by funders at different points in their process. Participatory grantmaking draws on broader participatory philanthropy approaches but zeroes in on how funding decisions get made. Why? Because money is power, and power dynamics are ubiquitous in philanthropy.

Participatory grantmakers do not only acknowledge and talk about power; they break down barriers that keep people powerless through an approach that realigns incentives, cedes control, and upends entrenched hierarchies around funding decisions. To practitioners, participatory grantmaking isn’t a tactic or a one-off strategy; it is a power-shifting ethos that cuts across every aspect of the institution’s activities, policies, programs, and behaviors.

Interviews with more than thirty participatory grantmakers around the world, conducted as part of the research for Candid’s GrantCraft publication Deciding Together: Shifting Power and Resources Through Participatory Grantmaking, underscore why this approach needs to be taken seriously.7

First, these funders have found that involving people with lived experience in the grantmaking process leads to better grant decisions and outcomes. Second, the process itself increases participants’ sense of agency and leadership. For these reasons, participatory grantmakers believe funders who aren’t using participatory approaches may actually be impeding the impact they say they want to see.

Still, participatory grantmaking is a tough sell for a field that’s long struggled with power issues. And, to be sure, some funders—especially large institutions—tend to have more formalized policies and/or structures that make it challenging to dive into participatory grantmaking head first. It’s also hard to determine who exactly their constituencies are. Perhaps the biggest hurdle is a misperception that authentic participatory engagement requires an all-or-nothing approach. That leads to participatory grantmaking being dismissed by funders as “something we’ll never be able to do.”

Some funders who want to experiment with participatory approaches say they’re hesitant because they’re not sure what the “rules” are. One of the beautiful things about participatory work is that because it’s inherently iterative and relational, there is no “right way” to do it. So, while there is general consensus about the values that drive participatory grantmaking, there’s considerable variation in how it’s practiced.

Some participatory funds, for example, are completely peer led (in that everyone making funding decisions is a member of the population or community the fund supports) and do not include any paid staff or trustees from the foundation itself. Other funds are peer led when it comes to grantmaking, but donors and staff play a role in other parts of the process (like providing grants-management support). Still others involve both peers and donors in reviewing, selecting, and making grant decisions.

The good news is that funders that may not be able to immediately (or perhaps ever) hand over decisions about grantmaking, have (as noted above) several options for incorporating meaningful participation in their work before, during, and after those decisions are made. They can also experiment with participatory grantmaking in one or two program areas to see whether and how it works for them.

Internally, they can institute hiring policies that favor participatory experience; encourage staff to collaborate across programs; involve staff from all ranks in policy discussions; and stipulate a number of board seats for peers. And they can support field building through research on and evaluation of the approach.

…

So where do feedback and better listening fit?

Participatory grantmakers agree that understanding and practicing the art of good listening are essential first steps toward authentic and meaningful participatory philanthropy; but if the goal is authentic participation, they’re insufficient. Funders that don’t commit to making changes based on what they hear from participants may lose credibility and participants’ trust, because direct action is a critical part of ceding power and empowering participants to feel heard. Involving participants and then carrying on with business as usual does nothing to shift who has the power, and disregards community knowledge.

Given the above, perhaps the challenge for philanthropy isn’t whether it’s going to encourage more feedback and listening—which are important—but rather whether the latter can serve as the baseline for moving toward more two-way communication, collaboration, and action in which non-donors are seen as equal partners with donors and other traditional power holders.

There could perhaps be no better time to figure this out. According to the World Economic Forum, philanthropy is at a turning point, and there are several directions it could take, one of which is transforming it into something that “is not seen as merely a tool for the powerful to entrench their advantage.”8 That will mean finding “ways to give away not only money, but also power”9 by democratizing philanthropy through participatory approaches, including the grantmaking process.

Will philanthropy follow other fields that are embracing participatory approaches, because it understands that impact and innovation aren’t just the purview of experts anymore but now include people who can bring their lived experience to bear in important decision making about their lives, communities, and futures? Feedback and better listening are definitely the first steps toward that goal. Long-lasting change, however, will only occur when the field fully embraces participation’s transformative potential by trusting participants, valuing their lived experience and wisdom, and, ultimately, ceding more control and power to them.

Notes

- Cynthia Gibson, “Lessons from Citizen Journalism—the Promise of Citizen Philanthropy,” in Sarah Armour-Jones and Jessica Clark, Global Media Philanthropy: What Funders Need to Know About Data, Trends and Pressing Issues Facing the Field (Philadelphia: Media Impact Funders, 2019), 30–32.

- See Cynthia Gibson, Participatory Grantmaking: Has Its Time Come? (New York: Ford Foundation, 2017), 26.

- Cultivating Community Engagement Panel, Engaging Residents: A New Call to Action for Community Foundations (Kansas City, MO: CFLeads, July 2013).

- IP Staff, “Philanthropy Awards, 2018,” Inside Philanthropy, accessed May 27, 2019,.

- Rhodri Davies, “Philanthropy is at a turning point. Here are 6 ways it could go,” World Economic Forum, April 29, 2019.

- This section was excerpted, with some changes for context, from Gibson, “Lessons from Citizen Journalism.”

- Cynthia Gibson, Deciding Together: Shifting Power and Resources Through Participatory Grantmaking, ed. Jen Bokoff (New York: Candid, 2018).

- Davies, “Philanthropy is at a turning point.”

- Ibid.

- Gibson, Participatory Grantmaking; and see Christopher Cardona, “Has the time come for participatory grant making?,” Equals Change (blog), Ford Foundation, November 10, 2017.