February 21, 2018; The Conversation

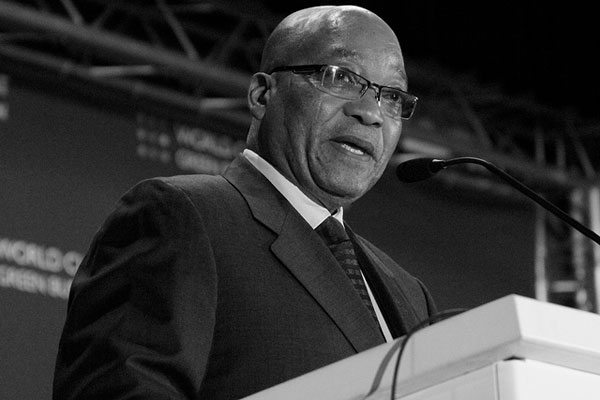

Mohammed Diatta’s commentary in The Conversation offers a brief prognosis of democracy in Africa following the departure in mid-February 2018 of South African president Jacob Zuma—one of the latest African leaders to vacate office. Diatta is careful to state that not all of Africa’s departed presidents were deposed and cites the divergent examples of Angola, Liberia, and Zimbabwe. However, and perhaps unwittingly, Diatta appears to rehash some longstanding distortions of political order in Africa. There have been countless debates about this, and there isn’t enough space here to bring them all into critical conversation, so this article highlights just the most pressing gaps.

Firstly, not enough attention is paid to the reasons why some of Africa’s less popular presidents have fallen. Zuma and Ethiopian prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn are but the freshest casualties of a wave that began with the “North African Spring,” a wave propelled by movements of ordinary women and men who have tired of what Diatta calls “the old order.” That wave has ebbed over the years, but it is resurgent now, even in the face of violent suppression, and it is not yet done purging those leaders who would stand in the way of true people’s power. There is consensus that these revolts have not brought about desired change, but is the envisaged change the same for people protesting on the streets of Africa’s capitals as it is for those purporting to support it from the world’s political nerve centers/metropoles?

Starting from the title, “Africa waves some leaders goodbye: but is the democratic deficit any narrower,” the notion of a democratic deficit runs through the article. It appears to play on the myth that this situation is peculiar to Africa, an inaccuracy that is tackled in this Guardian article from 2016. The truth is that there is a global deficit, to the extent that there are democratic flaws even in those countries that have arrogated to themselves the dubious distinction of democracy promoter and champion. Again, this tag doesn’t acknowledge the gains made in countries like Benin and Ghana within the frame of democracy and good governance. Further, amid recognition that there are different forms of democracy and government around the world, the whole idea of democratic deficit stems from divergent assessments and perceptions of compliance with the liberal democratic model of government. So, when Diatta writes, “The [African Union] must, more than ever, have all its member states sing to the tune of democracy,” the question that arises is, “Whose tune?”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The article makes several broad-sweep statements that reproduce the reduction of Africa to a monolithic entity. They lose ground against Nic Cheeseman’s proposition that there are “three (or four, or five) Africas” as far as democracy goes. Given these different representations of democracy, convergence does not seem likely or desirable. As Claude Ake posits, African democracy must and will find its own path, and that it is not inherently bad for being different from the norm.

It’s proper to speculate on the fate of democracy in Africa. But the current focus on how the departure of the current generation of leaders will enhance democratic practice is only half the puzzle. The question this article should really be asking is if and how well this wave of change that has uprooted leaders in its wake since the North African Spring will resituate political power from African elites and their Western allies to the ordinary men and women who put them there.

Diatta alludes to the need to “overhaul” the system, but that system, built as it is on free regular elections and popular representation, has proven unwieldy in the context of the complex cultural compositions of many African countries. The greatest value of the departure of Zuma and his colleagues is to rekindle debate around governance in Africa in ways that seek solutions to the quandary in which it has languished since the 1960s: Will it continue to battle its way toward a foreign concept of democracy? Or will it find and tread its own path?—Titilope F. Ajayi