February 24, 2020; Philadelphia Inquirer

The preamble of the US Constitution, written in 1787, begins, “We, the people,” not “We, the white men”—and yet voting was largely restricted from the beginning to white males, with universal adult suffrage only truly the law of the land after the Voting Rights Act passed nearly 180 years later in 1965.

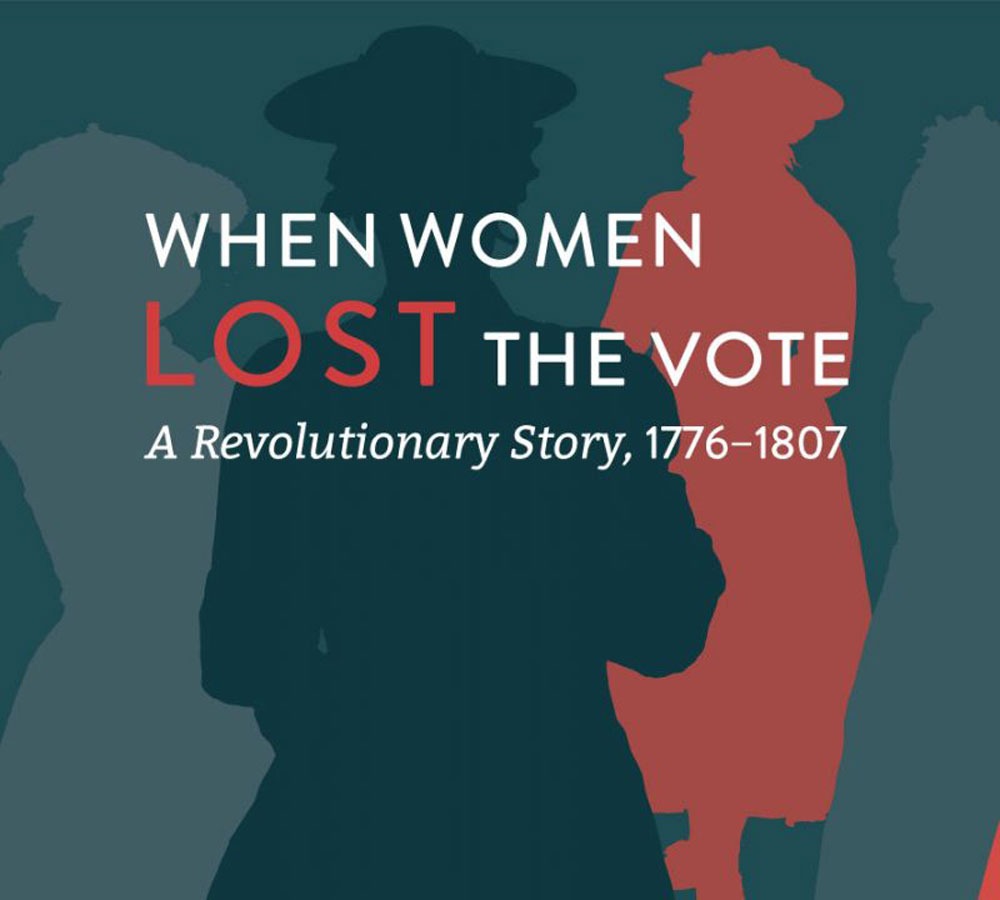

But “largely restricted” does not mean completely restricted. From independence until 1807, New Jersey allowed free Blacks (slavery was not completely eliminated in New Jersey until 1846) and women to vote. This year, the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia is hosting an exhibit to tell the tale of voting rights won—and lost.

The title of the exhibit is “When Women Lost the Vote: A Revolutionary Story, 1776-1807.” It will open August 22nd and run through March 28, 2021. As Stephan Salisbury in the Philadelphia Inquirer details:

From 1776 in New Jersey, the year of American Independence and the boiling stew of egalitarian ideas it unleashed, until 1807, “all inhabitants of this colony,” including women and people of color who fulfilled residency and age requirements and were “worth fifty pounds” could go to the New Jersey polls and “vote for Representatives in Council & Assembly; and also for all other publick Officers that shall be elected by the People of the County at Large,” according to the law.

It was right there in the state constitution of 1776. Then, in 1790, to clarify, the legislature reworded the law to say “he or she” could vote. No mistaking that voting was not limited by gender, and there was no limitation placed on free people of color, either.

For the exhibit, curators scrutinized polling lists from early elections and found the names of 163 women on voting rolls. Salisbury writes that “Marcela Micucci, curatorial fellow in women’s history for the museum, went through archives across the state and discovered the hard evidence of women’s names written down in the poll lists.”

Philip Mead, the museum’s chief historian and director of curatorial affairs, tells Salisbury that this provides hard evidence that did not previously exist of women voting in the state. Evidently, far more than 163 women voted, but “There aren’t many poll lists that even survive,” Mead tells Salisbury. Mead adds that the historical record shows that urban and rural areas “embraced and accepted” voting by Blacks and women during the period of open voting.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The history of New Jersey’s voting rights is fascinating. Salisbury’s story only scrapes the surface. A detailed scholarly account is provided by historian Linda Garbaye, a professor at Université Clermont Auvergne in France (located about 225 miles south of Paris).

The right of women and free Black votes to vote, and the ultimate repeal of those rights in 1807, was clearly tied up with partisan politics. As Garbaye explains, “Women were generally considered as Federalists…often from the Quaker community, and many of these voters came from the western part of the state.”

Garbaye adds that, “The role of women in the Quaker community was considerable; they could be ministers and travel from one place to the other in the goal of preaching Quakerism, and they could also organize their own meeting sessions. The influence of Quakerism on women’s political rights, resulting from their egalitarian principles, is put forward by some historians who establish links between Quaker legislators and the expansion of voting rights in favor of women.”

As the Federalist Party (associated with John Adams and Alexander Hamilton) lost political power in the early United States and the Democratic-Republican Party (associated with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison) increased its dominance, the rights of women and free Blacks to vote came under attack. It may be less than surprising that ultimately their rights were rescinded in the name of preventing fraud. As Garbaye explains:

In some New Jersey contested elections, one notes an important level of fraud and corruption, for example in 1807 when voters of the county of Essex were asked to decide the site of the county’s courthouse between two politically rival places, Newark and Elizabeth. One of the consequences of this highly contested vote was to suppress the voting results later, and to reform voting qualifications as a means to avoid corruption and fraud…

Negotiations took place between the main political groups which resulted in the exclusion of minorities, among them women, from the suffrage, even though fraud concerned all voters.

As this centuries-old New Jersey example reminds us, using allegations of voter fraud to restrict voting rights in the US is hardly new.—Steve Dubb