This article is from the fall 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

Where we stand.

We are living and working on Treaty 7 lands, the traditional territory of the Niitsitapi, Tsuut’ina and Stoney Nakoda Nations, and part of Métis Region 3.

The challenges that networks seek to address are systemic and are impacted by structures, policies, and histories that create injustice across lines of race, gender, class, sexuality, and ability. We strive to fight against this in our work.

We stand as allies of Black, Indigenous, and peoples of color.

We advocate for nesting the economy within the environment, not the other way around.

We are grateful to all who have supported and contributed to our understanding of networks over the past seven years. Our network scientist colleagues; fellow network strategists, learners, facilitators, and enablers; the people part of the networks we’ve had the pleasure to work with; and the Human Venture Institute have all provided invaluable contributions to our caring, thinking, and practice.

Thank you.

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

“I hereby call to order the Morning Coffee Steering Committee. Our agenda item today is to decide what kind of coffee Alvin will order this morning.” After thirty minutes of intense deliberation, the group takes a vote. The final tally is: 3 for cappuccino, 1 for flat white, and 2 for drip. Majority rules. Decision made. Alvin will buy a cappuccino.

This scenario is obviously ridiculous. No one needs a Morning Coffee Steering Committee. When it comes to matters of caffeine, we are well equipped to make decisions for ourselves, quickly and easily: the stakes are low, the choices are obvious, and there are very few people involved. That being said, the reverse is also true: When we’re working in networks with others on complex issues, the way we make decisions is more complicated, and the stakes are higher.

There is not one form of governance that enables empowerment. The most effective structures will depend on where the group is starting from and what it’s trying to achieve. The impact of COVID-19 has proven that governance structures need to be adaptive and fluid to meet the challenges that nonprofit networks are facing. This article explores three governance archetypes and seven characteristics that support leading-edge nonprofit network governance.

High quality networks are loose, fluid, ambiguous, and emergent; rely on distributed leadership; have messy accountability structures; and often come together to address long-term, complex challenges. By definition, this is a rejection of the hierarchical, structured ways we work in conventional organizations. This also means that some of the more standard ways of making decisions, which have proven to be incredibly efficient and effective in certain contexts, aren’t appropriate in nonprofit networks. As strategies are forced to change or evolve for networks, so should their governance structures shift. Especially when networks are facing times of crisis and uncertainty, being able to empower their members is paramount to successfully navigating uncharted territory.

Ultimately, the way that we make decisions is inevitably intertwined with what we’re trying to achieve and how.

Governance: What and Why?

“Governance is how society or groups within it organize to make decisions.”1

Ultimately, governance is about how we organize ourselves to make decisions. When we’re working as a team, it is critical to ensure that the process of making decisions is clear and visible. This enables the group to adapt these structures as challenges and opportunities emerge.2

It’s easy to focus on the structures of governance that we can see: advisory boards, stewardship groups, steering committees, organizational charts. It’s far less common to think about what these structures are trying to achieve. What are we making decisions about? What kinds of relationships are these structures supporting? Whose voices are included? Do these structures support engagement? Empowerment? Self-authorization? Shared voice? Does it matter?

Over the past six years, we’ve been trying to figure out how to build effective governance structures within networks.

What is the decision-making process? Whose voice is included in decision making? How is accountability structured?3

What’s Special about Nonprofit Networks?

“With clarity comes confidence, with confidence comes commitment.”4

If governance facilitates decision making, there are particular challenges in networks, where people are expected to step into leadership and decision-making positions in a collaborative way. In fact, oftentimes you are relying on participants to choose to give their resources to the group. Therefore, in order to be effective, governance structures must empower people to engage with the network and feel able to participate.

Empowering people to act within a nonprofit network can be tricky, because the work tends to be ambiguous, messy, and supported off the sides of people’s desks. This isn’t necessarily problematic, but it is essential to understand whether this ambiguity is causing people to feel unclear or confused. Having a sense of clarity is critical for one’s ability to engage and commit. This clarity might be achieved through processes and structures, but it can also be achieved through relationships and spaces that encourage people to be vulnerable and act even if they’re unsure. Any approach to empowering people to act within a network should be supported by the network’s governance structures.

If you can empower people through a feeling of safety and connectedness, they will offer you things you would never have imagined.

However, there is no one-size-fits-all. Some people feel empowered by very strong top-down guidance. Telling someone what to do might not sound like empowerment, but some people require top-down instruction in order to feel they have the clarity and confidence to contribute. Others feel empowered and engaged by contributing in ways that are open-ended and loose. They shut down when they are told what to do and how to do it. So, in that case, a more open-ended governance structure will empower them to contribute in meaningful ways.

People feel empowered for different reasons, and those reasons can change over the course of the collaboration.

To the extent that a nonprofit network empowers people to collaborate, contribute, engage, and continuously think about, care about, and improve the network, it is successful. One reason for this is that networks thrive when intelligence and leadership are distributed. Ideally, many people across the network understand its strategy and are taking responsibility to move things forward. Part of being able to do this is to have structures and processes that honor and leverage what people care about and give them a way to bring it forward, even if it feels outside the scope. If you’re building capacity in a network, the governance will need to change and adapt to the people involved, their individual capacities, and the stage of the collaborative.

And there are some cultural aspects within networks that enable or derail their success. For example, governance approaches can either support or get in the way of trust,5 a sense of safety, and connection6—all of which are important for a healthy network. Governance should be a mechanism for creating and supporting the culture or behaviors you want to see in the group. The needs, and corresponding governance structures, will change as individuals, context, and the network change. This is especially apparent in times of crisis or rapid transformation.

If the trust and relationships in a group aren’t naturally occurring, how can the governance approach support that goal?

Governance can also help to reinforce or undermine a network’s values and mission. If a network values transparency, transparent decision-making processes can reinforce that value within the group, while secretive ones can undermine it. Being consistent with the stated values also helps when a group is under stress, when it is easiest to yield to unhelpful behavior.

What Network Characteristics Do We Need to Pay Attention To?

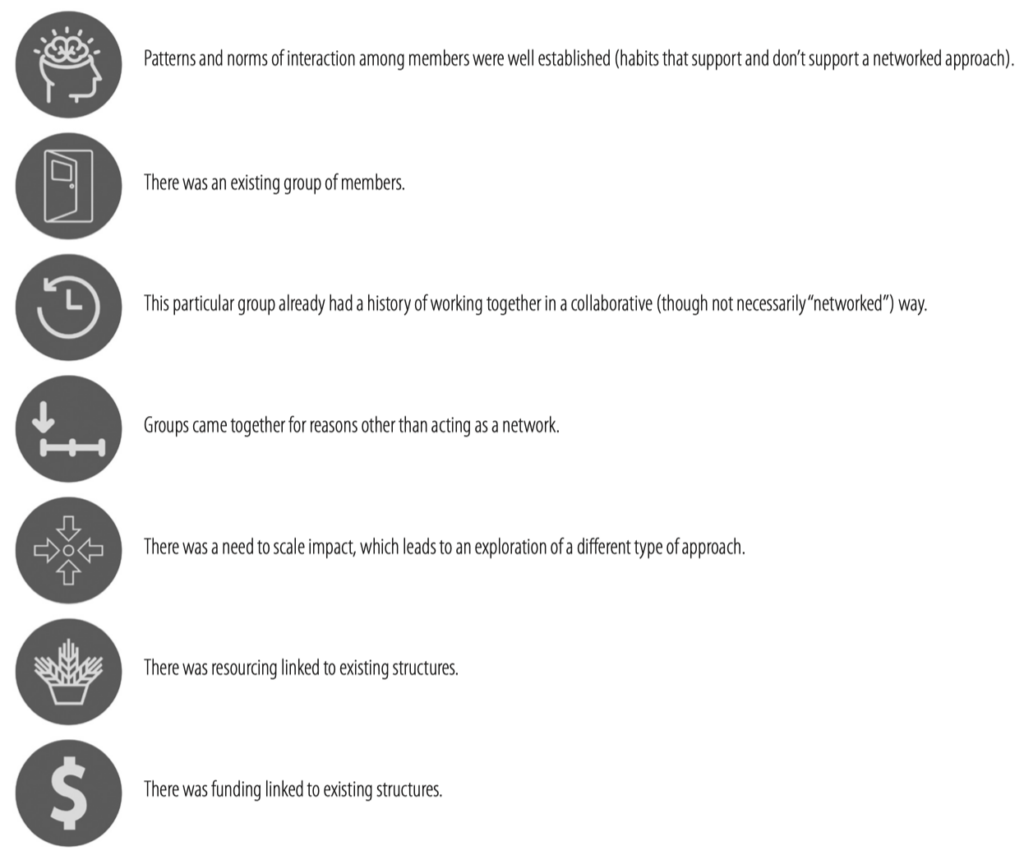

The type of governance structures you build depends on your network’s starting place. We’ve identified seven dimensions that should inform how you make decisions about governance.

Level of comfort with a network mindset

In effective nonprofit networks, individuals feel that their voices are heard, they’re treated fairly, the process is transparent, the group has power, and their colleagues are contributing value to the group. This is all in a context that tends to be ambiguous, more fluid, reliant on relationships, and dependent on healthy communication. It’s important that governance structures empower people to act while also encouraging them to adopt a network mindset.

Characteristics of participation

People participate in networks for different reasons. In some cases, participation is mandatory: individuals might be required to attend by their nonprofit, or nonprofits might be mandated by their funder. In other cases, participation is restricted: participants might have to meet certain criteria to engage. Finally, participation can be entirely voluntary and open.

History of collaborative attempts

The outcomes of and experience with previous networks will influence the assumptions that people have about what a network is, what is possible, and the opportunities and challenges ahead. It’s often necessary (and difficult) to undo people’s presuppositions about the work. Outside of formalized collaborations, there are also histories of individual and organizational relationships. It’s always worthwhile to understand the nature of these relationships and how they might be leveraged, be improved, or act as barriers.

Impetus for the network

Networks start for different reasons. Sometimes, funders mandate that people collaborate with one another. Other times, the need for a network emerges organically or as a result of grassroots efforts. Moreover, a network strategy might be building on another effort (with existing resources, engagement, and expectations), or starting from scratch.

System pressures

Every network will exist within a broader context. That context might be ripe for a networked approach: there could be strong leadership, healthy information flows, and ample resources. In contrast, the system can also be in flux, be generating a variety of pressures on potential participants, and/or be promoting toxic, competitive relationships.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Resources of the core group

The types of resources that the network has access to will impact the opportunities and constraints in the groups’ decision-making process. In addition to people’s time and energy, which are an enormous resource in a networked approach, this also applies to financial resources for communication, evaluation, project management, and coordination.

Characteristics of funding

The resources that the group has access to are closely related to but also different from the specific nature of and requirements of funding. The amount of funding (and whether it is short or long term), reporting requirements, and ideas about outcomes can all impact the way a network builds its strategy and its approach to governance. It’s also important to pay attention to the funder’s comfort or discomfort with long-term planning, and its level of involvement in the initiative.

Archetypes: The Tapestry, the Container, and the Trampoline

The following governance archetypes—the tapestry, the container, and the trampoline—illustrate how different approaches to governance enabled three different networks to build capacity to engage participants, supporting their common desire to work together and contribute to the goals of the network. The seven dimensions are helpful to think about across these archetypes.

The Tapestry

I trust you know what you are doing—and this is a place for you to do it, share it, and for us to build on it.

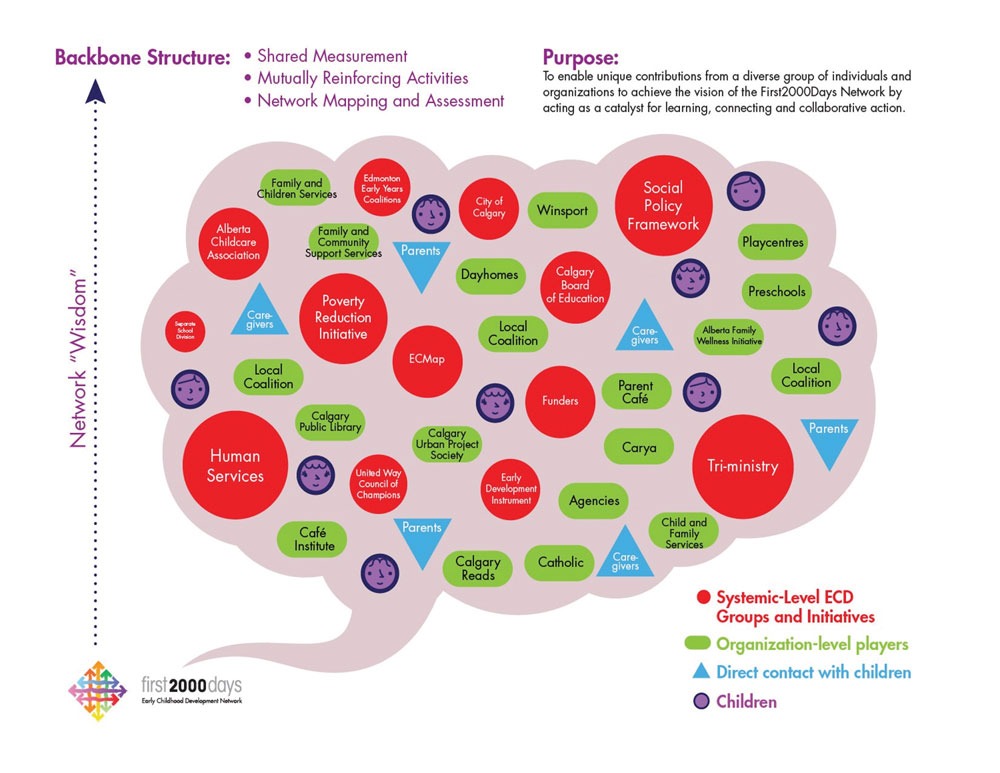

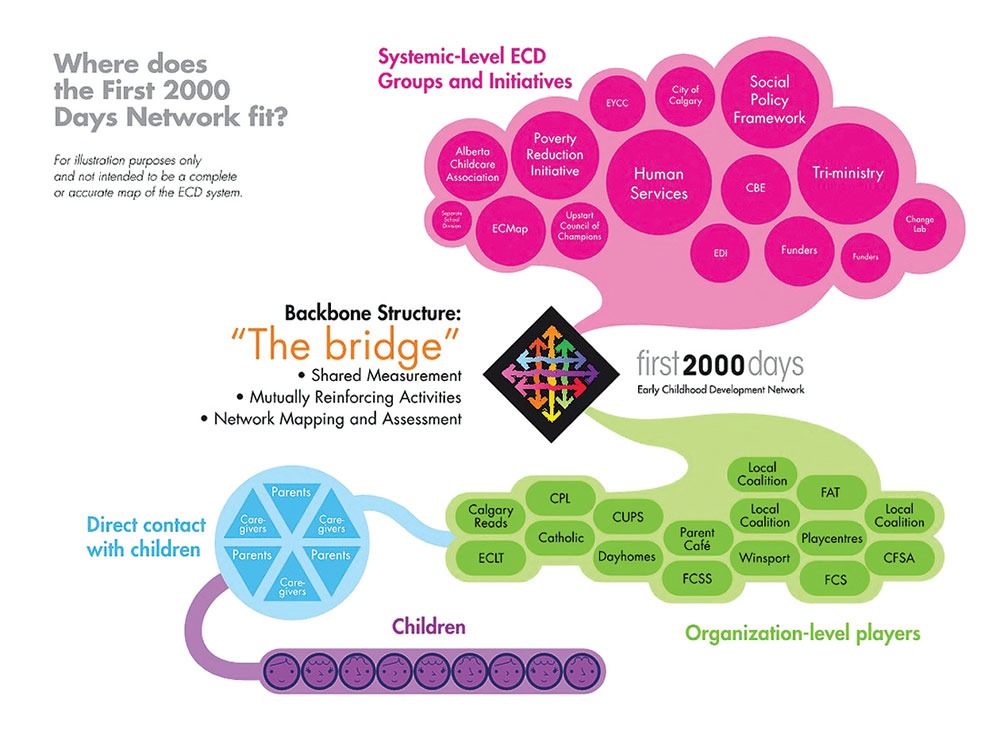

The First 2000 Days Network emerged because of an opportunity: the government was releasing data on, and funding grassroots coalitions focused on, early childhood development. The network saw this as an opportunity to share, link, align, and leverage the emerging and existing work in the sector. It was funded for three years, and the only requirement was to explore the preconditions for a collective approach to addressing the number of children who were not progressing appropriately in one or more areas of development. There was an enormous amount of space given to exploration and to creating a strong foundation.

Because it came about in a grassroots, organic way, the network had very little “legitimacy” or formal power. This starting place also reflected an intentional pushback against past collaborative efforts that were funder driven and “invitation only.” People wanted something that felt and looked different. This meant that, by definition, those who were most involved in the network were also the most comfortable with the ambiguity, openness, and relationship-based approach (otherwise, they just opted out).

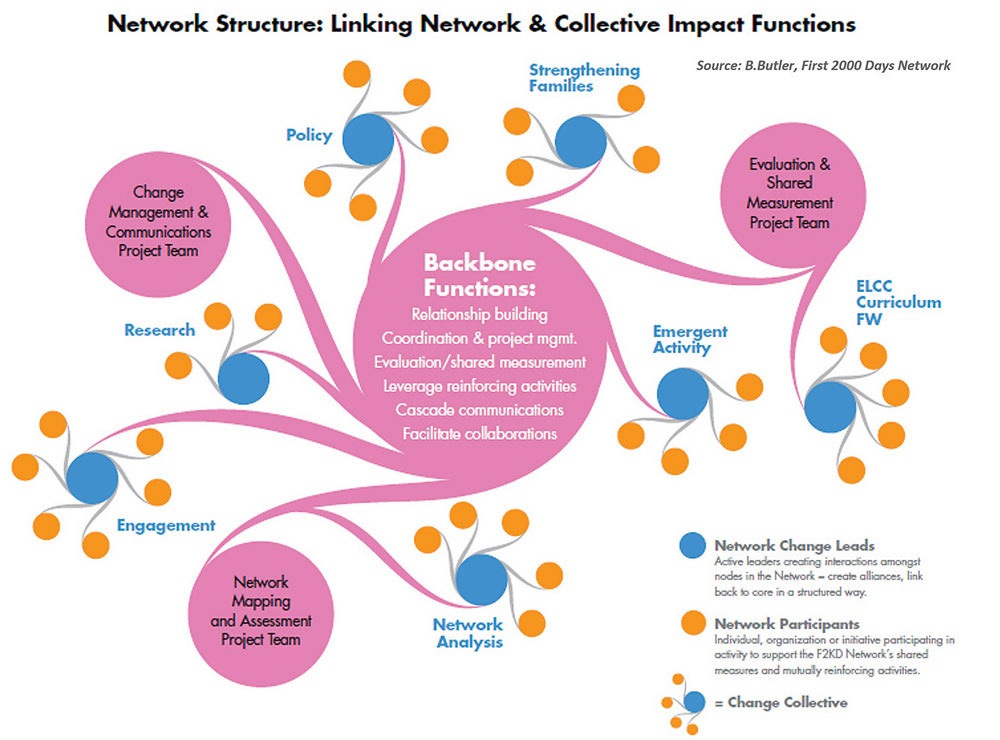

With that starting point, the network’s governance was built to reflect its core function: acting as a bridge between the work going on at the community, organizational, and system levels, as well as working to link, align, and leverage all of that activity. It took almost three years for the First 2000 Days to articulate its role in the system.

The First 2000 Days leaned into its organic roots: whoever wanted to step into the work was empowered to do so. People were explicitly encouraged and trusted to do what needed to be done on behalf of the network. This structure encouraged participants to be “network weavers”: to bring the network’s strategy into their everyday work and to bring their everyday work back to the network table.

The First 2000 Days leaned into its organic roots: whoever wanted to step into the work was empowered to do so. People were explicitly encouraged and trusted to do what needed to be done on behalf of the network. This structure encouraged participants to be “network weavers”: to bring the network’s strategy into their everyday work and to bring their everyday work back to the network table.

This lack of traditional organizational structure emphasized the feeling that people could step in and support the network in whatever way they were able: it empowered them to take action. The governance processes were set up to communicate that participants in the network were the experts, knew what needed to be done, and were trusted to do it.

There was no formal reporting or hierarchy within the network. The group met once a week for six years to ensure that the people who were engaged at the time could see and hear the most strategically significant opportunities around the table and contribute to them. A handful of consultants were tasked with some of the core operations for the network: evaluation, communication, network weaving, and engagement were all resourced on a part-time basis.

The Container

We all know what we’re trying to achieve; now we can govern around that.

The next group already had a collaborative strategy, but they wanted to explore what might be required to deepen that or shift it to a more intentional, networked approach. That meant that the group already had a history of working together, norms, processes, and structures guiding that work, and expectations of what would be most effective. Funding was also often linked to their existing structures.

The first step to building governance in this context was to be explicit about the structures and processes that had been guiding the group up to that point. How did they currently make decisions? How was that approach helpful? How was it insufficient? How did they expect it to change by taking a networked approach?

From there, it would be possible to leverage the existing container and shift it in ways that approximate a more robust and intentional network strategy. One of the biggest risks here is throwing the baby out with the bathwater. It’s important to understand what made the group successful to date, why there was interest in shifting things, and the expectations surrounding the changes that were being made. Governance structures (like any structure) can be external ways of keeping people accountable to the behavior changes that they’re striving toward. It can provide the crucial clarity that is required for people to feel able to participate in a new way, especially when they are used to something different.

Governance structures can provide the clarity required to participate in a new way.

The Trampoline

We have a clear process; now we can work together to prove the concept and get things done together.

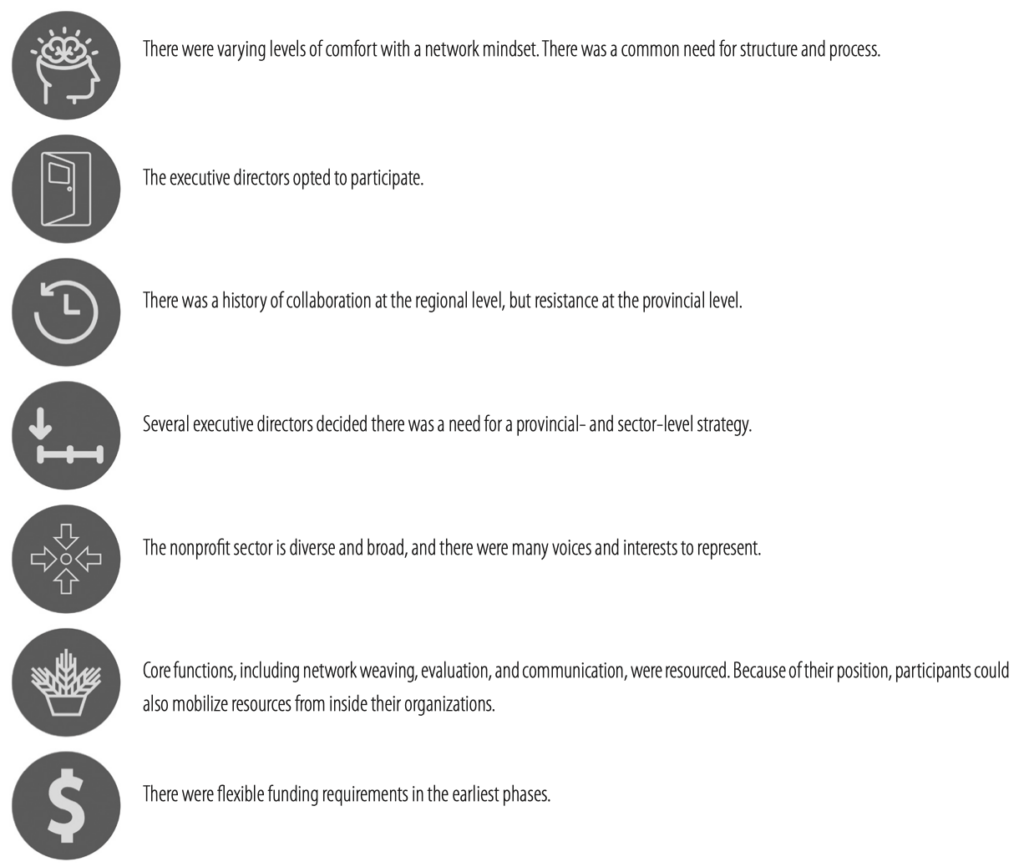

The Alberta Nonprofit Network (ABNN) started with a group of executive directors of organizations that serve the nonprofit sector in Alberta, Canada. Although it had been a topic of discussion for decades, there was no history of collaboration at a provincial level (there was at a regional level). Because of their position within their organizations and the sector, there was incredible organizational—but varying collaborative—capacity. The fact that all of the core participants were formal leaders within their organizations meant that there was an enormous potential to leverage this formal authority for change. Moreover, all of the people involved had experienced success in an organizational setting, and valued the processes, structures, and relationships that make organizations work. These are almost always different from the characteristics of a network, which means a lot of time will be spent building new ways of working together.

ABNN’s funding allowed them time to explore, and also hire some network weaving and evaluation capacity early on, which helped to intentionally build the network capacity. However, as the network scaled, there was some impatience to move toward action, there were different ideas about outcomes, and there was a resulting need for more resources to match participants’ ambitions for change.

The network was structured with a tight group of network stewards “in the middle.” There were terms of reference and formalized decision-making processes, supported by tools like a decision tree and scoping forms. The decision tree embedded questions that reflected a networked approach (i.e., is this leveraging existing capacity?) but was a formal structure to guide decision making. This approach used structures that were recognizable in an organizational context, and adapted them to function in a way that supports healthy network development. These structures, which were familiar and reassuring, become a way for participants to practice engaging in the network. Bouncing off these structures helped maintain momentum and trust in an uncomfortable new way of working. It provided them with the structure they needed to start to work and engage with one another, which is the only way to build healthy relationships.

Governance based on organizational familiarity was the proxy for trust and foundation for momentum.

The Archetype Trap

“…I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”7

Like any framework, archetypes are helpful because they simplify a more complicated reality. They point out some of the patterns that might be useful to pay attention to in your own context. That being said, they are only useful to the extent that you acknowledge the complexities of your own context. While we hope that some of these pieces resonate with you, no starting point is the same. Our best advice is to pay attention to the governance structures that will empower people in your own evolving, nuanced situation. This is especially relevant in this current period of rapid change in the nonprofit sector and within the communities it seeks to support.

To the extent that you’re able to do this, you are more likely to design a healthy nonprofit network. The whole point of networks is to be more effective as a whole—governance should be actively helping you increase levels of:

distributed intelligence

caring

responsibility

resources

capacity

adaptability

understanding

such that the group “sees what needs to be done, can do it successfully, without being told what to do” to address complex, dynamic, emergent social issues.8

…

Ultimately, the group’s ability to mutually reinforce intelligent assessment of the territory is at the core (you can enable people to address all the wrong problems—something to avoid). The collective ability to intelligently define the problem and solve it is the ongoing governance opportunity for all of us. Because social change—and the networks being used to address it—is by nature adaptive, emergent, and complex, it is all the more essential to develop adaptive, emergent, and complex governance and leadership. We cannot meet the transformational needs of our society without redesigning how we interact with one another, make decisions, and hold one another accountable. Nonprofits seeking to drive change through networks and collaboratives will need to build their adaptive governance capacity based on empowerment, trust, and belonging. The uncharted territory we are facing requires nothing less.

Notes

- Institute on Governance, “Defining Governance,” accessed August 19, 2020.

- See Institute on Governance, “Five Principles of Good Governance,” in “Defining Governance.”

- Institute on Governance, “Defining Governance.”

- Darrin Hicks, “Assessing the Quality of Collaborative Processes” (presentation, Network Leadership Training Academy, College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences, University of Denver, 2019).

- Danielle M. Varda et al., “Core Dimensions of Connectivity in Public Health Collaboratives,” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 14, no. 5 (September-October, 2008), E1–E7; and see Visible Network Labs.

- Daniel Coyle, The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups (New York: Bantam Books, 2018).

- Abraham H. Maslow, The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 15.

- Ken Low, The Human Venture & Pioneer Leadership Journey: Reference Maps, 16th ed. (Calgary, Alberta: Human Venture Institute, Action Studies, 2016), 121.

Blythe Butler and Sami Berger are partners in Collaborative Management. They work together to design, lead, and implement collaborative management systems, leveraging their expertise in change management, network science, and evaluation to help networks understand their contexts and achieve their social and system change goals. Butler is the founder of Atticus Insights. She is currently supporting the development of multiple networks and collaboratives, using network analysis, developmental evaluation, and capacity building to improve both process (systems) outcomes as well as program and client-level outcomes. Butler’s practice focuses on change management, evaluation, and capacity building to support the development of adaptive learning cultures within organizations. Berger is the founder of Curious Compass. She works with organizations and initiatives that are striving to make a meaningful change and are interested in thinking critically about their strategy.