Technology has produced a new generation of men and women with great wealth. As the Rockefellers and the Packards did, many tech billionaires are now turning their attention and their resources toward making the world changing the world, albeit with strategies that may or may not have staying power, resonance, or legitimacy. Those things aren’t needed if the money is the donor’s own without moderating influences and if the donor is lacking in humility.

This trend has spawned an industry often referred to as “impact investing,” when new major donors turn to advisors to help them decide where they can make the greatest difference.

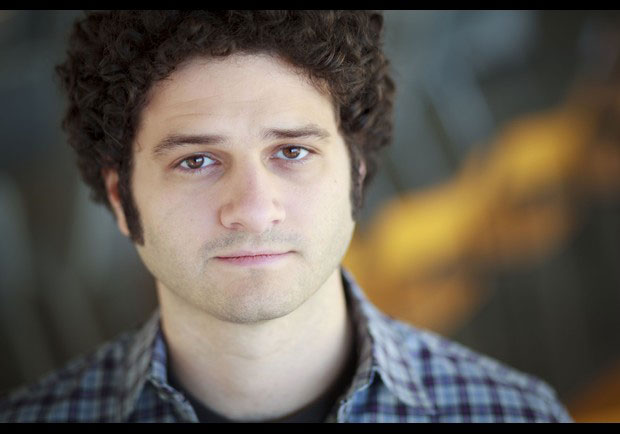

Cari Tuna and her husband, Facebook cofounder Dustin Moskovitz, have dedicated $13 billion for charitable purposes, described their giving philosophy to Times reporter Vindu Goel. “The thing we focus on is expected value. It’s all part of doing as much good as we can with the resources we have.”

Through their foundation, Good Ventures, they take a direct, hands-on approach to determining where to invest themselves and their money. As is said on the website, they see existing problems as the failure of existing nonprofit organizations and governments and their operational strategy.

We’ve learned about the limitations of traditional philanthropy. The lack of transparency. Difficulty measuring impact. Few clear feedback loops to allow for iteration and improvement. At the same time, we’ve heard from some of the most innovative and effective philanthropists, nonprofits and companies about what’s working, and what’s promising.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The philanthropic advisory firm GiveWell explains why it has selected a series of direct service overseas programs as models of good philanthropy. “We understand the sentiment that ‘charity starts at home,’ and we used to agree with it—until we learned just how different U.S. charity is from charity aimed at the poorest people in the world. Helping people in the United States usually involves tackling extremely complex, poorly understood problems. Many popular approaches simply don’t work.”

The search for great ROI leads, as it did in their businesses, to the search for unique breakthroughs. In investing in the new and novel, they are willing to experiment and seek to disrupt. William Foster, head of consulting at the Bridgespan Group, described this approach to the Times. “Tech people tend to be interested in more early-stage start-ups…These philanthropists typically support disruptive new ideas, get more directly involved in their giving, and show a willingness to move quickly to another approach when one fails.”

Examples abound of tech philanthropists finding a new solution for a significant problem that they think will be a “game changer,” backing it with a large investment and then moving away when success does not come. Mark Zuckerberg was a $100 million donor to Newark’s public schools, and then he was gone when the results were not immediately forthcoming. The Gates Foundation invested even more heavily in a series of efforts to improve public education and then quickly moved on when they did not see enough value in their impact.

This may be the best way to run a young tech business: Search for a new idea that has great potential. Get there fast. If the idea works, you have the next iPhone or Facebook and huge profits. If the idea doesn’t make it big in the marketplace, cut your losses and go on to the next idea—if you are able to stay in business.

For organizations whose purpose is to respond to human needs, this is a dangerous turn. Yes, we should seek to do our work better and more efficiently. But demonstrating ROI is more difficult. Often, services are needed even when they do not cure the problem. Providing a shelter for a victim of domestic violence meets a necessary, immediate need, but it does not guarantee the victim won’t return to the relationship and the abuse. Will changes to the way we teach preschool result in a more successful adulthood for those children? It’s difficult to know in the timeframe imposed by some new (impatient) philanthropists.

The existing nonprofit world is imperfect, and improvement in how we do business should be our goal. But we also need a level of stability to keep in place an infrastructure upon which many lives depend. Will this new generation of philanthropists have the staying power the nonprofit sector needs? Or will their great wealth and confidence in their own search for disruptive answers to hard problems leave a weakened support structure behind when they move on the next problem that hits their fancy?—Martin Levine