August 17, 2015; NPR, “Hurricane Katrina: 10 Years of Recovery and Reflection”

NPR’s story, “After Katrina, New Orleans’ Public Housing is a Mix of Pastel and Promises,” offers a ground-level profile of the transformation of that city’s public housing following the displacement of thousands of low-income families. The story has a refreshing “lived-in” approach to what works and what’s missing in the new projects.

What tenants like about the new public housing is what you might expect: larger units, with amenities like wide closets and modern kitchens, and a safer, quieter environment with an absence of gunshots and drug activity. Here’s what tenants don’t like: tougher screening, tougher rules, no gardening out front, no informal gatherings and events, high utility bills. In sum, excluding the utility issue, “it doesn’t feel like home.”

This is a serious problem that plagues public housing and HUD philosophy. Micromanagement of public housing residents is a legacy of the “social improvement” theme in the original public housing legislation and decades of rule-driven directives from D.C. Whether public housing authorities know how to operate outside of a rulebook is an open question. This is one area where a more relaxed (dare one say “entrepreneurial”) management style that treats tenants as customers instead of clients could reduce some tenant irritations. Don’t look to nonprofits to fill that role; nonprofit management companies too often combine the worst features of “do-gooder” intentions and authoritarian directives.

Still, HUD’s thinking may be evolving on this issue. Here’s an example: For years, HUD promoted Neighborhood Networks in public and subsidized housing as a way to bridge the digital divide. These computer labs were open during “business hours” and staffed with coaches who worked for the management company or for nonprofits hired by the management company. Tenants using Neighborhood Networks were monitored as to how they used the equipment and where they surfed the Internet. Education and vocational development were “promoted,” while watching movies and playing games, not so much. Contrast that approach to the new White House initiative to support getting broadband access out of the management office and into the tenants’ homes, without any management oversight.

Incorporating services into this housing, what Secretary Castro referred to as “wrap-around services” in a Diane Rehm interview, could create a risk for nonprofit service providers eager to take advantage of a nice, secure workspace and a “captive audience” of clients. Will these social service providers be subject to management needs that could conflict with the interests of their clients?

HUD’s Service Coordinator program provides some examples of these risks of conflicts. At least in Ohio, where I practice, tenants know that the “social worker” in their building is often a management employee or contractor who can be compelled to report to management what should be professionally confidential information. One service coordinator complained to me that the property manager put a closed circuit camera above her office door to so he could see which tenants were consulting her. In many properties, the service coordinators carry out management functions like passing out management notices and organizing “tenant” meetings where the manager presides.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Building community is one area where nonprofits could break some ground, but they will need to be operating “completely independently of management.” Interestingly, that’s the standard in the HUD regulations for privately owned, subsidized properties. (Code of Federal Regulations 24 CFR 245). Community organizations, independent tenants associations, and agencies with a community building expertise should be in conversation with tenants about making “community” work from the ground up.

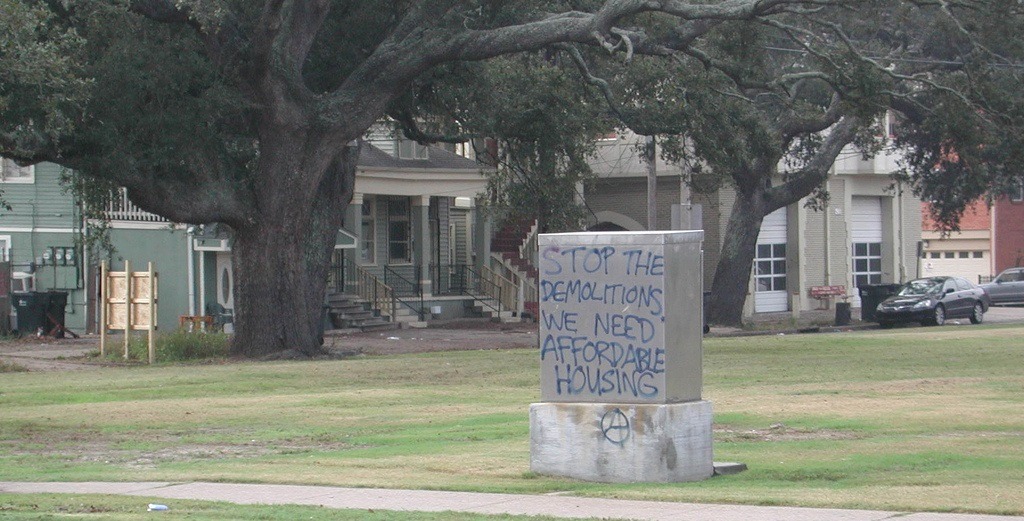

To advocates, analysts, and academics, public housing in New Orleans looks different than it does to the tenants in the NPR story. Three years ago, NPQ’s Rick Cohen asked:

Can NPQ Newswire readers give us their take on the performance of nonprofits and foundations in the pre- and post-Katrina treatment of poor people, low-income housing, and public housing in New Orleans? Is Arena on to something that hasn’t been aired—and should be—or is he blaming the wrong culprits for the displacement of the public housing (and black) population of New Orleans?

A recent article on Next City sheds little new light on Rick’s challenge. In CityLab’s account, local ineptitude required the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) to reach out to private sector developers: “‘That’s why we have developers,’ Fortner says. ‘The Housing Authority isn’t smart. Our developers have to use their creative juices to get us to the [goal of] 821.’”

Nevertheless, the charges of “privatization” of public housing that Rick questioned have only gained strength following the implementation of HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program across the country.

Since the turn of the century, HUD’s adopted a program development strategy that involves rolling out half-baked plans and then getting feedback and assessment that modifies and strengthens the program. The mark-to-market program was repeatedly described, sometimes by HUDsters, as “building an airliner while in flight.” Viewed in this context, the experience in New Orleans is a test bed for the development of HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration and Choice Communities programs.—Spencer Wells