September 26, 2017; Next City

Critics of government safety net programs often describe them as if they were opiates, addictive and debilitating. They claim that SNAP coupons, Medicaid, and other income support programs increase dependence on government aid and minimize a recipient’s desire to work and be self-supporting. From this perspective, the best thing government can to do help those struggling for economic survival is leave them to the magical power of the marketplace, rewarding hard work and punishing laggards.

Beginning in 2013, New York, followed a year later by Atlanta, has been part of a pilot project designed to test these assumptions. We now have results from an evaluation of the New York City experience that might change some minds.

The program, Paycheck Plus, was designed, according to NYC officials, to allow “rigorous testing [of] a new earnings supplement for low-income single adults—mostly men—with the goal of promoting work and reducing poverty.”

The project is a direct response to the downward trend in employment, wages, and earnings among the least skilled. As a new form of labor market policy (rather than income maintenance policy), it could have important implications for a next generation of interventions aimed at inequality in an information economy.

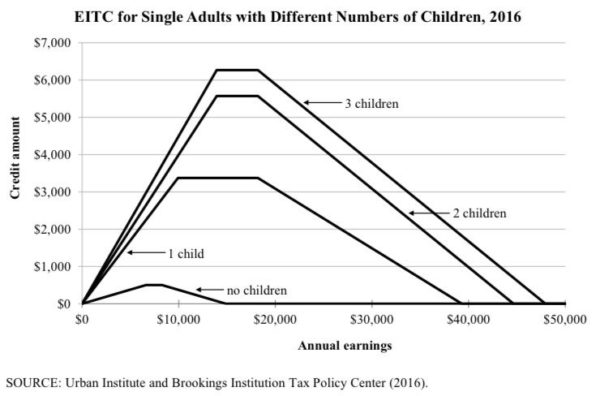

Using the federal Earned Income Tax Credit program as a model, Paycheck Plus focused on expanded benefits for single (and mostly male) households with no resident dependent children, a population EITC currently affords little benefit because single males are often seen as less deserving of help. For those participating in the pilot, the maximum tax credit was raised fourfold to $2,000 and the earnings ceiling for inclusion in the program was increased from $14,880 to $30,000 a year. While still below the higher levels offered to those with dependent children, this is a significant increase.

Using a rigorous research design, which included a matched control group who did not receive the increased tax credit, the study found that “there is no evidence that the program reduced work effort or earnings among those who had higher earnings when they enrolled.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In fact, third-party researchers from the evaluation firm MDRC found no evidence that the “bonus reduced work effort among those who had higher earnings when they enrolled in the study.” The researchers also found that participating in the program increased incomes of the working poor. The authors report that “on average, individuals in the program group had net earnings of about $10,049 in 2014 compared with $9,395 for the control group, a statistically significant increase of $654, or 7 percent. The increase in net earnings for the subsequent year was $645, or 6 percent.”

Not only did the financial situation of those in the program improve, they were willing and able to meet their obligations as noncustodial parents:

About 80 percent of noncustodial parents in the program group made a payment during the year, compared with 71 percent of those in the control group. Similarly, the program group paid on average $191 per month in child support, an increase of $54 over the control group.

Future research will allow us to see if these outcomes hold in communities, like Atlanta, with a lower minimum wage. And, longer-term analysis will provide further insight into how an expanded benefit term changes poverty rates, median household income, and participant health and well-being.

Matt Klein, executive director of the New York City Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity, described the meaning of this pilot in a press release:

Paycheck Plus is helping us learn what could happen if an effective antipoverty policy is expanded to benefit more low-income workers. In our changing labor market, too many people who work remain in and near poverty. We are showing how an Earned Income Tax Credit that provides more robust support to single adults without dependent children could be part of addressing this profound problem.

Paycheck Plus is demonstrating that efforts to help people in financial need do in fact help them and their families. When it is not possible to raise the minimum wage to a level that means working people can earn enough to afford food, shelter, healthcare, and education for their children, expanding the reach of the EITC can offer at least a partial solution. Saying no to both will ensure many continue in a state of avoidable poverty.—Martin Levine