This article comes from the summer 2019 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

For many nonprofits, the trade-off for spending time on so-called “capacity building” is questionable. In part, this may stem from thinking of capacity building primarily as an activity undertaken in times of stress. However, that framing can be limiting, in terms of both process and product. This article redefines the process of building capacity to clarify what it is, why it works, and what we hope to get back from it.

First, it’s important to recognize that as our economic and technological era has changed, so have the forms and functions of our organizations. Their boundaries are often more permeable. Staff members expect a different type of social contract with employers, one that allows them to more fully use their energy and intelligence—singly and as a group—to achieve personal and collective aspirations. As we work to solve intractable problems, we are ever more aware that effective governance requires cooperative action across multiple levels. Social transformation no longer rests on a single heroic leader or organization. Instead, creating a better world necessitates a broader coalition of networks, people, and cross-sector partnerships.

Increasing organizational effectiveness must therefore attend to all these facets of our work, as well as to issues with our own board of directors, organizational budgets, and so on. To effectively build capacity, we must pay attention to operating contexts and relational issues such as niche, influence, and accountability, as we operate in increasingly complex and interdependent environments. To stay stable in these new situations requires constant attention to capacity development, rather than only when something appears to have broken.

Capacity Building as Capital Building

While conventional views of capacity building have been useful to some nonprofit organizations, they don’t always make clear how various activities connect to each other and the larger system, or what difference the new capacity will make when developed. A way to overcome these challenges is to frame capacity building as capital building.1

Capital has been defined historically as an enduring asset that can produce more assets. While initially conceptualized in terms of money, financial instruments, and durable goods like buildings and equipment, today there is growing recognition that intangible assets such as knowledge, relationships, and reputation are equally essential to value creation and organizational success.

A starting point for this novel way of thinking is Alan Fowler’s model, inspired by the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals.2 The U.N. project identified multiple types of capitals essential to a thriving economy: human capital (e.g., mental and physical health); business capital (e.g., buildings and equipment); infrastructure or built capital (e.g., highways, airports); knowledge capital (e.g., science, information, education); natural capital (e.g., forests, agriculture); social capital (e.g., relationships, trust); and public institutional capital (e.g., the making and enforcement of laws).3 To that list, Fowler added financial capital (money), political capital (e.g., free elections, transparency, accountability), and human competencies that activate the capitals (e.g., values and motivation).

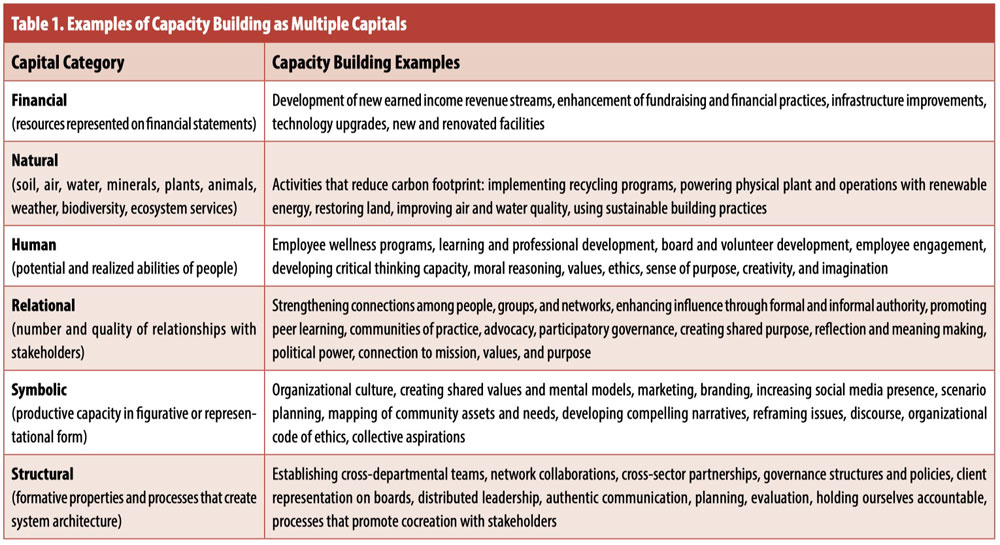

My research categorizes these various assets into a typology of six groupings (financial, natural, human, relational, symbolic, and structural) as a framework to connect resources and value creation potential in a holistic way across multiple levels.4 Table 1 (above) presents an overview of these six categories with examples for each.

What Is Capacity Building?

While there are many frameworks for capacity building, there is no generally accepted definition of it.5 Capacity building in federally funded programs often seeks to develop five competencies: (1) managerial (e.g., governance, finance, and data systems); (2) programmatic (e.g., implementation, monitoring, assessment); (3) revenue enhancement (e.g., fundraising, donor relations, developing earned income streams); (4) leadership development (e.g., volunteers, employees, and community members); and (5) community systems (e.g., asset mapping, building collaborative networks).6 Capacity building therefore embodies both tangible and intangible forms (e.g., tangible techniques and equipment, intangible motivations and processes).

Capacity can be developed across multiple levels, including micro (individuals), meso (organizations), and macro (sector, network, system, society). Capacity-building programs often seek to develop multiple levels simultaneously. For example, programs may enhance people’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (micro level) in ways that strengthen culture, norms, resource procurement, management practices, and connections to other organizations (meso level) and encourage participation in collective action networks (macro level). Thus, it can be helpful to think of capacity building through the lens of who (e.g., people, organizations, networks), what (e.g., knowledge, skills, processes), and how (e.g., training, peer learning, technical assistance).7

In terms of time horizons and scale, capacity initiatives generally fall into three categories: (1) short-term planning and training; (2) longer-term organizational effectiveness initiatives; and (3) sector-strengthening programs that develop systemic knowledge and encourage information exchange.8 Ideally, capacity building produces multiple benefits simultaneously, such as learning and peer interaction.

The Hewlett Foundation’s guide to choosing an organizational assessment tool discusses these and other options.9 The report emphasizes two important considerations. First, the tools that nonprofit and funding organizations have found to be most effective are usually customized and context specific. Second, the instrument chosen is much less important than the process. In order to assure that tools are meaningful to stakeholders—and that they are used—an inclusive, participatory approach is key to cocreating them.

Why Does Capacity (Capital) Building Work?

Like capacity building, a multiple-capitals approach seeks to grow resources and make them more productive. A capital-based understanding provides explanatory power for why capacity building works. Albert Hirschman described economic development as a process of making latent resources manifest so they can be deployed productively to create value.10

In the nonprofit sector, Jeffrey Brudney and Lucas Meijs’s description of volunteers is an example of how latent generative potential of tangible and intangible capital can be activated.11 As volunteers donate their time (temporal capital) and energy (human capital), they increase a nonprofit’s productive capacity for mission fulfillment. Many of these resources (e.g., volunteer interest, motivation, commitment) can be transformed from potential into kinetic forms, similar to ways energy can be activated and converted (e.g., chemical to electrical).12 Like all capital assets, human resources require care and support to remain productive.13 A capital-building framing makes a clear case for why investing in volunteer development and coordination is a wise use of funds.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

An example of such mobilization is the Service Enterprise initiative that encourages organizations to develop and leverage volunteers by translating “the skills, expertise, connections, and passion […] into meaningful service that meets the programmatic and operational needs of the organization. For every dollar these organizations invest in volunteer engagement, they can realize a return of up to $6.”14 Research on hundreds of such organizations found they produced a 23 percent average increase in the number of volunteers annually. These new volunteers generated an average of 2,700 service hours per organization, or 1.5 FTE’s worth of labor valued at $63,000.15 For example, the California State Library system’s “Get Involved: Powered by Your Library” initiative, designed to expand volunteerism in public libraries, generated an average of 750 new volunteer referrals per month, leading to a 27 percent increase in volunteers serving in libraries.16

This new understanding of capacity building as capital building paves the way for systematic, coordinated action across multiple levels (individual, organizational, network, community). Conceptualizing capacity as multiple forms of capital is a framework applicable at any scale (micro, meso, and macro) to guide activities such as planning, doing, evaluating, and reporting. For example, a nonprofit organization can use the capital typology as a program tool to help clients identify what capabilities they would like to develop and the values they would like to express.17 In this way, multiple forms of capital serve as a proxy for capabilities. At the organizational level, it can serve as a reporting tool to show donors how their support has generated increasing returns. At the community level, community well-being indicators can similarly be framed as multiple forms of capital that create quality of life and human flourishing.18

Using a framework applicable at multiple levels is important because it creates an architecture for emergence—the generation of new qualities from interaction effects. An example is mission fulfillment as described above, which can be seen as an emergent property that arises from the interaction of volunteers and staff. With respect to systems, nonprofit organizations at the meso level generate the emergent property of public benefit (macro level). Maintaining and channeling this potential requires a structure that can accommodate building multiple capitals across multiple levels. It also allows you to track how resources developed at one level can cycle back to become new resource inputs at another level.

Finally, it is important to note that, in this typology, the term capital does not entail commodification or an instrumental conceptualization of resources that are in fact priceless (i.e., incommensurable, having intrinsic value in and of themselves). Amartya Sen expressed this concern with the growing use of the term human capital, which he felt neglected the essential distinction between means and ends.19 He argued—rightly—that people should not be seen simply as factors of production. Rather, people and their well-being are the very purpose for which economies and organizations exist.

For this reason, it’s important to use a capital framework that preserves the potential for development and expansion of human freedom that enable people to “lead freer and more worthwhile lives.”20 I designed the typology with this in mind, which is why it includes both instrumental resources (means) and expressive resources (ends, e.g., values-based goals), such as moral capital (concern for goodness and the welfare of others, a dimension of human capital) and spiritual capital (e.g., purpose and values, which are components of relational capital) to account for and develop resources such as equity, inclusion, and reciprocity.

Adopting a capital-building approach also has larger implications. Our culture’s singular focus on monetary indicators (e.g., financial statements, the gross national product) marginalizes and obscures the supporting elements (i.e., civil society) that make financial returns possible.21 Similarly, prioritizing a single form of capital (financial) promotes marketization that puts democracy, values, cooperation, and accountability at risk.22 A remedy to this is to depict the full array of capitals on which organizational success and societal well-being depend.

How Can Busy Organizations Find Time for Capital Building?

Viewing capacity building—and nonprofit work in general—as the development and recirculation of multiple forms of capital can help overcome the perception that building capacity is an additional task. In fact, with thoughtful program design, building capital can occur through service delivery. An example is Mary Emery and Cornelia Flora’s case study, which illustrates how investing in one type of capital produced a “spiraling up”—a cascade of positive feedback that activated other latent forms of capital to create over time the emergent property of economic development and community well-being in rural Nebraska.23 This occurred as community leaders leveraged their social networks (relational capital) to recruit people to participate in a leadership development program (human and intellectual capital), resulting in three cohorts of people increasing their knowledge and leadership skills.

Other outcomes and impacts identified by Emery and Flora in the evaluation included the emergence of changing norms, such as greater appreciation for, and participation in, community involvement (symbolic and political capital), which then transformed structural aspects as more youth and people of color got involved. The program ultimately attracted new financial investments, planned-giving bequests, entrepreneurial initiatives, and manufacturing infrastructure. This spiraling-up dynamic reflects the economic concept of increasing returns, the tendency of gains to produce more gains.24 This is a compelling rationale for philanthropic investment.

A similar example of how multiple forms of capital were identified and developed through program design is Ashley Anglin’s 2015 case study in South Rome, Georgia.25 There, the multiple-capitals approach was used for planning and community development. Previously, a community coalition had identified fifteen unique community assets. But by using the multiple-capitals framework and including more stakeholders in the process, they identified eighty-five unique assets. Participants remarked that “thinking in capitals” enabled them to see many intangible community assets they had overlooked.

The process of categorizing the capitals also illuminated community strengths (natural and built capital) and needs (human and political capital). Anglin’s study found that the community capitals framework, “especially when imbued with the values of community empowerment, diversity, and inclusion/participation—is a valuable tool for helping stakeholders to approach community development from a systems perspective, combat hopelessness, and foster common language and plans for the future.”26 The Puerto Rico Community Foundation, under the leadership of Dr. Nelson Colón, is similarly using a community capitals framework to guide disaster recovery and create grassroots prosperity and equity.27

…

The takeaway message from these and other cases is that a multiple-capitals approach to program design can simultaneously produce mission fulfillment while increasing organizational effectiveness.28 A multiple-capitals framework integrates planning, service delivery, evaluating, and reporting, thus filling in potholes and pitfalls of capacity building and paving a road for smoother integration of organizational activities and stakeholder accountability.29

A multiple-capitals approach can help nonprofit organizations build capacity dependably and systematically across multiple levels. Further, this approach offers a cohesive and compelling rationale to support strategic decision making and present a clear case for philanthropic support. Developing tangible and intangible forms of capital resources (e.g., social, political, spiritual, and reputational) through the design of multiple capitals is a promising systematic framework for organizational, community, and sector capacity-building efforts.

Notes

- Elizabeth A. Castillo, “Beyond the Balance Sheet: Teaching Capacity Building as Capital Building,” Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership 6, no. 3 (July 2016): 287–303.

- Alan Fowler, Civil Society Capacity Building and the HIV/AIDS Pandemic: A Development Capital Perspective and Strategies for NGOs (Oxford, UK: INTRAC, December 2004).

- UN Millennium Project, Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals (New York: UN Millennium Project, 2005).

- Elizabeth A. Castillo, “Qualities before Quantities: A Framework to Develop Dynamic Assessment of the Nonprofit Sector,” Nonprofit Policy Forum 9, no. 3 (October 2018): 1–14.

- Paul C. Light and Elizabeth T. Hubbard, The Capacity Building Challenge, “Part I: A Research Perspective” (New York: Foundation Center, April 2004).

- Amy Minzner et al., “The Impact of Capacity-Building Programs on Nonprofits: A Random Assignment Evaluation,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43, no. 3 (June 2014): 547–69.

- Chris Cardona, Julie Simpson, and Jared Raynor, “Relational Capacity: A New Approach to Capacity Building in Philanthropy,” Responsive Philanthropy (Winter 2014/2015): 9–12.

- Light and Hubbard, The Capacity Building Challenge, “Part I.”

- Informing Change, A Guide to Organizational Capacity Assessment Tools (Berkeley, CA: William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, October 2017).

- Albert O. Hirschman, The Strategy of Economic Development (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1958).

- Jeffrey L. Brudney and Lucas C. P. M. Meijs, “It Ain’t Natural: Toward a New (Natural) Resource Conceptualization for Volunteer Management,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 38, no. 4 (August 2009): 564–81.

- Mary Bates, “How Does a Battery Work?,” Ask an Engineer, MIT School of Engineering, May 1, 2012.

- Emma Spalti, “4 Key Results of Talent-Investing,” Fund the People blog, April 23, 2018.

- Amy Smith and Sue Carter Kahl, “Service Enterprises: Strategic Human Capital Engagement,” in Volunteer Engagement 2.0: Ideas and Insights Changing the World, ed. Robert J. Rosenthal (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 308–21.

- “Service Enterprise,” Points of Light, accessed May 22, 2019.

- Carla Campbell Lehn, “Leading Big Volunteer Operations,” in Volunteer Engagement 2.0: Ideas and Insights Changing the World, ed. Robert J. Rosenthal (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 322–33.

- Thomas Wells, “Sen’s Capability Approach,” in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed May 22, 2019.

- Elizabeth A. Castillo, “Voices from the Field: Vital Signs—Catalyzing Community Well-being Indicators,” Nonprofit Quarterly, December 7, 2017, nonprofitquarterly.org /vital-signs-community-wellbeing/.

- Amartya Sen, Choice, Welfare and Measurement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997).

- Ibid., 160.

- Baruch Lev, “Intangible Assets: Concepts and Measurements,” in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, ed. Kimberly Kempf-Leonard, vol. 2 (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier, 2005), 299–305.

- Angela M. Eikenberry and Jodie Drapal Kluver, “The Marketization of the Nonprofit Sector: Civil Society at Risk?,” Public Administration Review 64, no. 2 (March 2004): 132–40.

- Mary Emery and Cornelia Flora, “Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework,” Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society 37, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 19–35.

- Paul Krugman, “The Increasing Returns Revolution in Trade and Geography,” in The Nobel Prizes 2008, ed. Karl Grandin (Stockholm: Nobel Foundation, 2009), 335–48.

- Ashley E. Anglin, “Facilitating community change: The Community Capitals Framework, its relevance to community psychology practice, and its application in a Georgia community,” Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice 6, no. 2 (October 2015): 1–15.

- Ibid.

- See, for example, Cyndi Suarez, “Two Philanthropic Approaches to Strengthening Puerto Rico,” Nonprofit Quarterly, February 13, 2018; and Steve Dubb, “Remaking the Economic System in Puerto Rico: A Case Study,” Nonprofit Quarterly, May 16, 2019.

- See, for example, Kyle A. Pitzer and Calvin L. Streeter, “Mapping Community Capitals: A Potential Tool for Social Work,” Advances in Social Work 16, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 358–71; see also Gary A. Goreham et al., Successful Disaster Recovery Using the Community Capitals Framework: Report to the North Central Regional Center for Rural Development (East Lansing, MI: North Central Regional Center for Rural Development, Michigan State University, May 31, 2017).

- Rebecca McCaffry and Nick Topazio, Integrated Reporting in the Public Sector (London: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, December 12, 2015).