March 6, 2017; Bloomberg

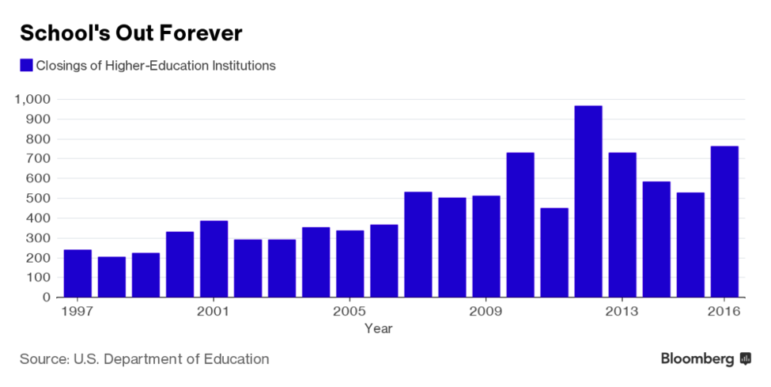

According to the U.S. Department of Education, more than 750 higher education institutions closed last year, including for-profit schools. Among these closing schools are private nonprofit colleges no longer able to fill the gaps between revenue and expenses and sustain operations while debt remains unpaid. While very few of the higher education institutions closing each year are private nonprofit schools, the annual number has tripled since the recession and is anticipated to remain stable or increase further, according to a 2015 Moody’s report. Many of the schools most at risk have fewer than 500 students and are affiliated with religious denominations.

When a college or university goes bankrupt, what happens to its endowment? Most financially troubled schools have modest endowments, and some of the funds within the endowments are restricted by their donors to specific “for good, forever” purposes rather than immediate general support like debt relief. For example, Art Rebrovick, restructuring officer for Virginia Intermont College, which closed in 2014, said, “The endowment was on the books for $4 million, but it had been leveraged and used for faculty salaries so many times that there was just literally no money there.”

If there is money left, there can be a fight between creditors, or between successor institutions taking up the responsibility of educating students. When Chester College in New Hampshire closed, it designated New England College as the recipient of its residual assets. This practice follows state and IRS guidelines that direct dissolving 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations to give remaining funds to other nonprofits with similar missions, services, clientele, etc. However, the New England Institute of Art challenged the decision because it said that it was taking 92 percent of Chester College’s students and that act should be supported by the college’s residual endowment. Ultimately, the New Hampshire courts decided that the funds would be split 60-40 between the two schools, with New England College receiving the larger amount.

In most cases of nonprofit dissolution, executives and board members learn that the state attorney general is the nonprofit’s ultimate arbiter and trustee. The AG must sign off on asset distribution and has standing to challenge any distribution that, in the AG’s opinion, harms the state’s citizens or denies them appropriate access to assets intended for a public purpose.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Nonprofit dissolution is a seldom-addressed topic, so it’s not unusual for experienced executives, board members, and others to be unfamiliar with—and surprised by—the financial, legal, and emotional complexities associated with closing a nonprofit or merging multiple nonprofits into a single agency. In fact, many people don’t know that merging nonprofit organizations usually involves dissolving most or all of the merging entities, and these dissolutions ahead of a merger can be like small deaths in themselves. Disagreements about asset distribution, including endowments, is often an expression of the emotions associated with the dissolution process. These emotions, including board members’ and executives’ grief at losing their roles, belief in the entity, and commitment to it and its role in the community, can be among the unseen ingredients that decide whether or not a dissolution moves forward.

The impassioned backlash against a decision to dissolve was evident in the case of Virginia’s Sweet Briar College. NPQ reported on the alumnae-led successful opposition to the board’s decision to dissolve. School officials are cautiously optimistic that renewed and redirected focus and supplemental fundraising has improved the school’s chances for sustainability. Although enrollment reached less than 70 percent of goal, the school achieved an operating surplus of $2 million and “did not spend a penny from its $65 million endowment to operate, ending 20 years of draws in excess of a five percent target,” according to Tim Klocko, Sweet Briar College’s vice president for finance and treasurer.

Despite this success, there are still hurdles for Sweet Briar to overcome that may sound familiar to other troubled nonprofit institutions.An endowment of $85 million in 2015 is now reduced by $20 million after costs associated with the attempted closure and market fluctuations. Perhaps with a jaundiced view based on his own institution’s closure, Virginia Intermont College’s Rebrovik said, “It’s a nice story that they kept the school open, but the sad truth is that they’re most likely just delaying their fate, and making it an uglier closure than it had to be.” Whether or not that’s the case, the preservation of Sweet Briar’s endowment will be a key bellwether of Sweet Briar’s ongoing health.—Michael Wyland

Addendum: This article has been changed from the original version to reflect a more accurate source of the loss of Sweet Briar’s endowment assets.