This article from the Spring 2009 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “HIGH Anxiety,” was originally published on March 21, 2009.

Dissolution, or the closing of an organization in its current state, is more common than one might think. But when an organization seriously considers ending its life, it’s a difficult and complex process. It is a time of mixed and strong emotions for those involved, including a nonprofit board, senior staff, administrative and line staff, partners, and stakeholders.

An organization has to make the difficult and momentous decision to close for two kinds of reasons: (1) involuntary reasons (e.g., an external shutdown is required, usually initiated through the state’s attorney general’s office or the office of the secretary of state) and (2) voluntary ones (e.g., mission has been achieved, a financial crisis has taken place, board and staff have exhausted their energy and ideas, or internal interpersonal disputes have overtaken an organization).

By federal and state law, nonprofit organizations should outline in their articles of incorporation and bylaws all tasks and responsibilities regarding organizational dissolution, and these policies must be followed. But most nonprofit organizations have not drafted such policies and procedures. The purpose of this article is to outline the steps and tasks involved in dissolving a nonprofit organization. And it may serve as a guide for establishing a protocol for an “honorable and respectful transition for all.”1

Our approach is based on four essential principles:

- Like any organizational initiative, dissolution should be carried out with interpersonal integrity.

- A successful dissolution preserves an organization’s legacy and contributes to a positive collective memory of the organization.

- Laying the groundwork is essential to a successful outcome. Many authors and theorists have addressed this stage of the process. The Gestalt International Study Center discusses balancing the intimate with the strategic2, numerous authors talk about attending to group dynamics, Eunice Parisi-Carew and Ken Blanchard offer the team charter model3, and a model of governance as leadership has also been developed4. But no matter what it’s called or how you choose to address it, we are convinced that organizations must pay as much attention to the process of laying the groundwork for a closure as they should to the tasks of the dissolution itself.

- During this process, an organization should rely on a network of professional nonprofit experts, legal counsel, human resources support, and dissolution planning and implementation. While finances may be paramount in the minds of board members and senior staff, relying solely on internal resources may lead to a less-than-satisfactory outcome. Using expert input during the dissolution process can better ensure that all aspects are thoroughly addressed and that a board and staff groups are included in the right way and at the right time.

The process of closing a nonprofit organization takes many months. It is important that those implementing the dissolution are prepared for this time frame and equipped with responses to questions from the community about the status of the process.

The Decision to Dissolve

An organization’s board and senior management must pick up and carry the burden of this difficult emotional process, coordinate, and follow through on each step. This is a critical time for skilled leadership, governance, and generative thinking. Thus the decision must be well informed and thoughtful. For the purposes of this article, we assume that an organization’s board of directors and key staff have exhausted all reasonable alternatives (such as restructuring and downsizing, changes in leadership, mission refocusing, merging with another organization, etc.) and that these deliberations have been documented in official meeting minutes.

Defining Strategic Goals and Objectives in Nonprofit Dissolution

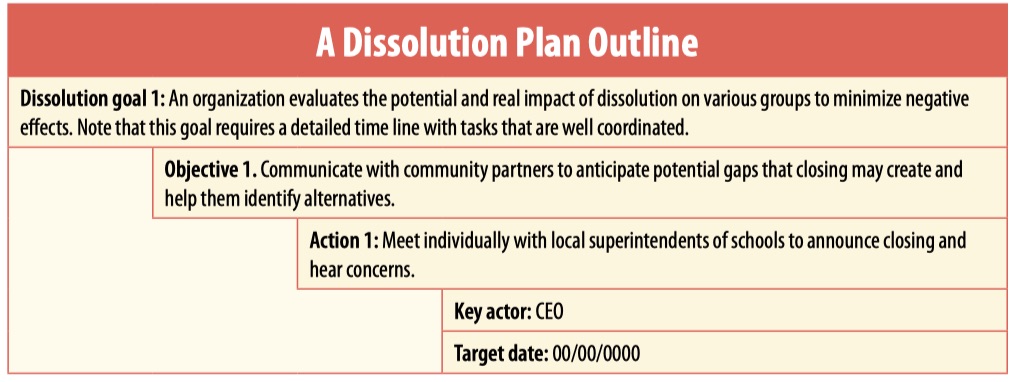

The dissolution plan should have strategic goals with objectives that cover the following:

- Areas of impact

- Asset distribution

- Preserving organizational legacy

- Announcements and communication

- Legal filings

Each strategic goal should have specific objectives with action steps, time frame or target dates, and personnel designated to each task.

The body vested with the power to make the final decision to discontinue an organization’s affairs should be identified in an organization’s official documents (e.g., articles of incorporation and bylaws). The decision must take place at an official meeting that is duly called and documented.

We also recommend that an organization’s board and key staff make the decision to dissolve privately. In the case of a nonprofit membership organization, a board must make a recommendation to membership for its consideration and approval. In most cases, this means that the information will then “go public.” As the dissolution plan develops, key players in the process should keep these information management issues in mind.

While we often advocate transparency, in this case we advise strict information control. A board and key staff must feel safe in exploring all issues without fear that the community or other staff will prematurely hear about plans that may never be implemented. You can imagine the effect on an organization’s credibility if the word were to get out that it was closing its doors, only to have a last-ditch fundraising effort become highly successful. In the meantime, staff may have launched job searches, and key community partners may harbor serious doubts about the organization’s ability to deliver quality services. To ensure solid information management, the question of where meetings take place is also a factor. As a board and senior staff explore the possibility of dissolution, there will likely be strong disagreement, frustration, and sadness. “Sound carries,” and administrative and line staff suspicions may increase because of additional meetings among power groups. Consider the possible ripple effects on the process.

Once the decision to dissolve has been made, board and key staff must have the time to debrief. Throughout the entire process, those who make the decision as well as the implementation team must have ample time and space to address their thoughts. Otherwise, they can’t adequately support administrative and program staff. Left unattended, emotions can give rise to doubts and dissent and, in turn, create additional problems.

After an organization’s board and senior staff have attended to the above tasks and prior to implementing the dissolution process, it’s time to engage in planning. Whenever possible, nonprofit dissolution should not be implemented prior to a solid period of thought and planning. Every board member must recognize that this period of intense work must be completed as soon as possible to minimize leaks and the inevitable increasing concern on the part of staff members who are not privy to the proceedings. Board meetings should take place more frequently. It is critical to establish secure email procedures with unanimous agreement among those involved. Frequent reminders about confidentiality guard against laxness.

An organization’s board should identify a planning group that includes the board chair and CEO as members. The planning group will be tasked with creating a detailed draft of the plan for presentation to the board. In addition, because of dissolution’s legal implications at both state and federal levels, we recommend that at this stage of planning an organization’s board engage legal council for the duration of the implementation process.

Developing a Comprehensive Plan

A plan for nonprofit dissolution should be translated into a formal document that includes several sections. It should be strategic and tactical in nature and must cover all main areas of the process.

Informing Stakeholders and Constituencies

The planning group should identify all the groups and individuals who must be informed about an organization’s closing. Each should have an articulated method of being informed, along with a designated person or group to provide the information and, if needed, required support.

Stakeholders to Inform and Processes in Organizational Dissolution

- Community at large (this may fall under a public-relations goal)

- Participants and clients

- How and when to inform

- Referral to alternative services

- Staff and human resources

- Recognizing staff

- Job-placement supports

- Determining severance packages (within legal and financial bounds)

- Determining last day(s) of work (will all employees leave at once or be phased out?)

- Funders, donors, and sponsors

- Board of director and advisory groups

- Honoring current and past board members, and other volunteers

Close Enough: Distributing Charitable Assets

By Scott Harshbarger and Alison Langlais

Shortly after the Thirteenth Amendment that abolished slavery passed, a donor’s bequest that was designed to “create a public sentiment that will put an end to negro slavery in this country” came under scrutiny.1

In Jackson v. Phillips, a court ultimately applied the doctrine of cy près to prevent the bequest from lapsing and to provide the funds for the “use of necessitous persons of African descent in the city of Boston and its vicinity.” Two centuries later, the doctrine of cy près—which means “as near as possible”—is still relevant when a charitable organization decides to dissolve.

Once an organization decides to dissolve, it must redistribute its assets. But it cannot simply close its books and haphazardly “re-gift” the pledges, bequests, and gifts it has received. Indeed, in addition to the standard procedures for dissolution applicable to all charities, those charities with assets to transfer at the time of dissolution have additional responsibilities.

Making the Decision to Dissolve

To minimize conflict that may arise later, an organization should agree—while it is robust—on the conditions that signal it is time to dissolve. These conditions, or triggers, may include the following: if a minimum number of employees can no longer be supported, if an organization’s donor base decreases by a certain percentage, and so forth. These triggers should be included in an organization’s governing policies.

Though procedures vary by state, the state attorney general’s Web site is a good starting point to determine a state’s specific dissolution requirements. In some states, the office of the attorney general is a necessary party to dissolution proceedings and must be notified and, in turn, give approval at various stages of the proceedings. Specifically, the attorney general may have oversight of the transfer of a dissolving organization’s assets and may monitor dissolution to ensure that a terminating charity’s assets are preserved. In many states, after filing a complaint for dissolution with the state court, a dissolving charity must also file a motion seeking the court’s approval of the transfer of its assets, naming the attorney general as a party to the motion.

Invoking the Doctrine of Cy Près

While a dissolving charity may have a destination in mind for its assets, a court will apply the judicial doctrine of cy près to determine whether the chosen destination is most appropriate. When the general charitable intention of a donor cannot be followed because it is obsolete, inappropriate, impracticable, or impossible—as in the case of an organization’s dissolution—courts still apply this doctrine to redirect charitable assets. Cy près is therefore applied to carry out a donor’s intentions as nearly as possible. Courts afford relief under cy près when doing so is the least restrictive method of preserving a donor’s charitable intent. Many statutes and dissolution procedures have embodied cy près and, in turn, made the doctrine more accessible.2

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Often, the administrative detail—that is, how the charitable purpose is accomplished—is not the essence of a gift, and a donor’s intentions cannot be met if cy près relief is not granted. Indeed, “where a main charitable purpose is disclosed with reasonable clearness, directions of the donor as to management and the precise manner of its application may be regarded as directory rather than mandatory, if necessary to carry out its leading purpose. It will be presumed that the details were meant to be subject to unforeseen and unforeseeable circumstances that may render them impracticable or illegal. In such cases, administrative duties may be varied, details changed, and the main purpose carried out ‘cy près,’ or as nearly as possible.”3

Upon dissolution of a charity, a court may use its discretion and modify the purpose of a charitable donation to place funds in a new entity. In this way, an organization’s assets can be preserved for charitable purposes in accordance with a donor’s original intent, even though the original object of a donor’s gift no longer exists. Indeed, courts assume that a donor would prefer that its donation be applied to a like charitable purpose rather than cease to have charitable purpose altogether. In application, courts consider evidence of the donor’s wishes had she realized that the particular purpose of her donation could not be carried out as planned.

Courts will not apply cy près, however, if there is no evidence of a general charitable intention behind a gift. If it appears that a donor intended a specific purpose for a gift and did not make a gift with a general charitable purpose, courts will allow the gift or legacy to lapse. The key to determining the original intent of a donor, and often the limitations meant to be imposed on a charitable donation, is an examination of the original recipient’s organizational purpose.

Cy Près in Practice

While the doctrine is not always invoked by name, cy près is alive and well and highly publicized when its application goes awry. Many may recall the legal battle over the proposed sale in 2002 by the Hershey Trust of its control in Hershey Foods Corporation. Over the past century, courts have applied cy près to discern the intent of Milton Hershey, who founded the Hershey Trust in 1909, though not always without conflict and criticism.

More recently, in late 2006, a legal battle ensued between Greenpeace and the Salvation Army. In 2006, a wealthy donor left some $264 million in his last will and testament to be divided equally among eight charitable organizations, including Greenpeace International and the Salvation Army. Unbeknownst to the donor, in 2005, Greenpeace International was absorbed into the Greenpeace Fund. Seeking clarification on how to effectuate the Greenpeace donation, the trustee of the donor’s estate filed a petition in state court, since technically Greenpeace International no longer existed.

Seemingly more opportunistic than charitable, the Salvation Army filed its own legal action to challenge the disbursement, arguing that the Greenpeace Fund was not eligible to claim the $33 million gift left to Greenpeace International because it was merely an affiliate. The Salvation Army instead advised that the gift would be most appropriately divided among the seven remaining charities, increasing its slice of the charitable pie by nearly $5 million.

Subsequently, philanthropy blogs and the media had a field day speculating whether under cy près the donor’s original intent was to bequeath part of the estate to Greenpeace generally or only to the defunct Greenpeace entity. Most observers agreed: the Greenpeace Fund was meant to be a successor to Greenpeace International, and the gift should remain within the Greenpeace organization. In the spring of 2007, however, the parties settled the dispute, and Greenpeace forfeited a piece of its bequest, walking away with a $26 million gift rather than the $33 million it was supposed to receive.

Indeed, though cy près is a helpful tool to relax impracticable restrictions imposed on charitable gifts, it clearly has its imperfections when a sizable donation is at stake.

About the Authors

Scott Harshbarger is senior counsel at Proskauer Rose LLP and the former attorney general of Massachusetts. Alison Langlais is an associate at Proskauer Rose LLP. Their governance and regulatory litigation practice focuses on providing counsel to nonprofit and corporate clients on a range of issues.

Endnotes

- Jackson v. Phillips, 96 Mass. 539 (1867).

- Massachusetts, M.G.L. c. 12, section 8(k), for example, states that a “gift made for a public charitable purpose shall be deemed to have been made with a general intention to devote the property to public charitable purposes unless otherwise provided in a written instrument of gift.”

- 15 Am. Jur. 2d Charities § 135, at 143.

Distributing Assets

The critical task of the disposition of assets must meet the standards of the Internal Revenue Service Code and any applicable state laws. In general, a nonprofit’s assets may not be distributed to a board of directors, staff, or other organizational insiders. Most states require that an organization’s assets be distributed to other charitable organizations or governmental bodies. These laws ensure that assets amassed for charitable or other nonprofit activities continue to be used for similar purposes.

The asset distribution component should delineate how all organizational assets will be distributed to other organizations or parties, including programs, cash, investments, equipment, supplies, and facilities. An asset distribution document should also include an organization’s programs and services as an asset. It may be able to identify other organizations that can adopt its programs, especially if a funding stream is associated with these programs. Thinking through which programs can be passed on may also keep some staff employed and part of the organization alive. This can be part of preserving an organization’s legacy. In the event that the preferred plan for the distribution of assets doesn’t work out, it’s also prudent to develop an alternate plan.

Preserving Organizational Legacy

Any nonprofit organization that has done marketing has addressed the question “What makes us unique?” Periodically, it’s a good idea to ask, “What would this community be like if we didn’t exist?” Identifying the contributions of an organization to its community is the first step toward understanding the organization’s legacy for constituencies. Once it clearly articulates its contributions, it must assess the depth and breadth of its impact. It is the real impact that constitutes the legacy, not just the effort of making a contribution. This information is an important part of an organization’s public relations and celebration.

Communicating Dissolution to Stakeholders

This portion of an organization’s plan details how an organization controls the release of sensitive information to each of the groups identified under a dissolution plan’s section on areas of impact. When it comes to communicating this kind of information, we all live in a “small town.” So dissemination must be orchestrated and coordinated. This part of the plan outlines to all involved what they can say, to whom, and when. It should also address what an organization will do if this aspect of the plan is violated.

In addition to an information-release schedule, an organization may want to institute mechanisms for responding to concerns and questions from the parties involved. Implementation is a pressurized and hectic time. As the organization works to implement the myriad details of dissolution, the task of responding to questions and concerns can get left in the dust. Thus having a clear response plan is helpful.

Finally, we strongly recommend creating written communication procedures that include the board, staff, and other key personnel and organizations.

Implementing Dissolution

Clearly the two key guiding documents for implementation are the nonprofit dissolution plan and a time line. As mentioned previously, these documents must incorporate all federal and state requirements.

Creating a Time Line

Coordinating the timing of each action in your plan is important. So, in the planning stage, ensure that target dates are feasible. A time line is derived directly from the target dates of the plan. We suggest developing a Ghent chart or a true time line. Regardless of the format, the time line helps those involved see how each element of the plan relates, interacts, and overlaps.

Filing Legal Documents

Generally, an organization’s first step in the documentation process is to file articles of dissolution with a state attorney general’s office and/or office of the secretary of state. The office then issues a public notice. When you develop your plan and time line, allot time for this step. Check with the IRS regarding requirements for your type of nonprofit. You may also need to notify the appropriate officials in your city and county. After filing these notifications, the organization continues to exist until all existing invoices and other business including legal procedures are completed. All other business, such as signing contracts and running programs, is no longer permitted.

Celebrating

Honorable and thoughtful leave-taking involves acknowledgment of the result of people coming together for a common cause and shared values. During the process of dissolution, it’s extremely valuable to reflect on the history of the organization and to create rituals that recognize the hard work and dedication of those who have been involved.

In addition to recognizing individuals, it’s also important to recognize the contributions of the organization as a whole. We are a culture of peoples and stories. Celebrating the story of an organization that is about to close is an important tradition that is all too often forgotten.

Remember, this process can be tricky to pull off. Some may be tempted to paint a rosier-than-realistic picture of an organization or its staff. Thus, this kind of celebration can be bittersweet and stimulate anger or sadness. The key is to plan different rituals for different groups and to be honest and appropriately open given the group for which this process is intended.

Closing

If your organization has considered dissolution, consider the steps and guidance here as an outline for the plan you ultimately put in place. Stressful challenges tend to exaggerate the best and the worst of the human condition. Leaders can expect that during the process of dissolution, all aspects of organizational culture will heighten. The strengths and the trouble spots between individuals, roles and positions, and divisions and groups may need rapid, clear, and direct attention. Calming any rough internal waters as quickly as possible improves the potential for a successful outcome.

The IRS categorizes many different types and subtypes of nonprofit organizations, which have a range of sizes and missions. We do not believe in a one-size-fits-all approach, but we hope this article offers guidance for organizations on the cusp of dissolution.

Endnotes

- Lee Bruder, The Five Phases of Board Development, Lee Bruder Associates, 2004.

- Sonia Nevis, Stephanie Backman, and Edwin Nevis, “Connecting Strategic and Intimate Interactions: The Need for Balance,” Gestalt Review, vol. 7, no. 2, 2003.

- Ken Blanchard and Eunice Parisi-Carew, The One-Minute Manager Builds High Performing Teams. New York: William Morrow and Co., 2000.

- Richard Chait, William Ryan, and Barbara Taylor, Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards, BoardSource, 2005.