November 28, 2017; MinnPost

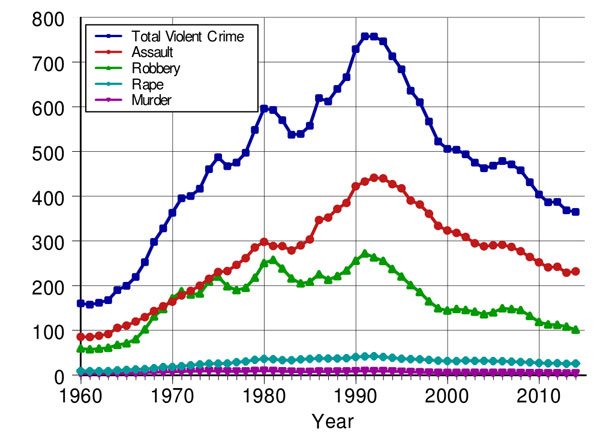

The US, as NPQ has noted, faces many fissures, but one area of marked success in the past two decades has been a dramatic decline in the crime rate. Yes, of course, the US is still violent, marked by all-too-frequent mass shootings, but hidden behind the daily blotter is a remarkable decline in crime. And nonprofits may have played a larger-than-understood role in that decline. Such is the argument advanced by New York University associate professor Patrick Sharkey and doctoral students Gerard Torrats-Espinosa and Delaram Takyar in an article published in last month’s American Sociological Review.

As Greta Kaul writes in MinnPost, the findings are “pretty striking: In more than 20 years across 264 cities, for every 10 additional nonprofit organizations focused on things like reducing crime, mitigating violence and building community per 100,000 residents, murder rates went down by nine percent. Violent crime went down by six percent, and property crime went down by four percent.”

Of course, correlation is not causation. But the American Sociological Review is not just any journal. It is, as the American Sociological Association notes, “the top ranked journal” in its field. So, the authors wouldn’t have gotten published if they didn’t control for other factors.

In fact, as Kaul writes,

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The study’s model accounts for other things that occurred around the time nonprofits boomed and crime declined, such as an increase in police force sizes and higher incarceration rates. It focuses on the addition of community nonprofits—those that work in preventing crime, neighborhood development, substance abuse prevention, job training and workforce development, and activities for young people—and not on nonprofits that work in areas including the arts, medical research and the environment that would be less likely to affect crime rates. The study also controls for the fact that nonprofits that have an effect on violent crime rates are more likely to spring up in more crime-ridden areas.

While the results varied across cities, in general, the cities with the largest increase in community nonprofits saw the largest drops in crime. New York City, for example, which added 25 community nonprofits for every 100,000 of its residents between 1990 and 2013, saw a larger than average crime rate drop.

Kaul adds that, “The researchers aren’t suggesting every nonprofit plays a role in reducing violence, but they write that there’s evidence that organizations that do things like summer jobs for teenagers, in-school programming, cognitive behavioral therapy and tutoring can have an effect on crime rates.”

In the journal article itself, the authors write, “It is easy to romanticize the efforts of [nonprofit] organizations and assume they were effective without any formal evaluation. However, it is also easy to dismiss or overlook the work of local organizations and to assume they did not play a meaningful role in reducing violence.”

The authors conclude: “As the practice of aggressive or violent policing and the expansion of the criminal justice system have met with growing protest, community-based organizations may become increasingly central to the effort to control violence within communities that are vulnerable to a rise in violent crime. We argue that the evidence presented in this article is thus relevant not only for understanding why violence fell in the 1990s, but also for reconsidering the set of actors and organizations that have the greatest potential to build stronger urban communities and control violent crime in the years to come.”—Steve Dubb