April 26, 2017; Pew Research Center

Given the last few years in the U.S. and the recent presidential election, new research by the Pew Research Center showing that “the relationship between religion and education in the United States is not so simple” is not surprising. Its recent survey explores the relationship between religious affiliation and educational levels among people in the U.S.

This information should be important to many nonprofits in that it helps to shape communications in some realms.

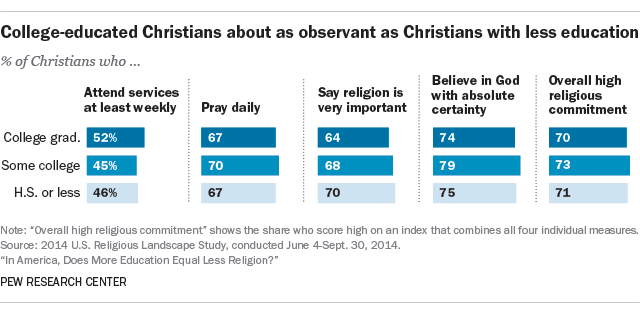

The study found that more education is correlated with less religion in every religious group except Christians. In fact,

Highly educated Christians are more likely than less-educated Christians to say they are weekly churchgoers…more than half of college-educated Christians say they attend religious services on a weekly basis (52 percent), compared with 45 percent of Christians with some college experience and 46 percent of Christians with a high school degree or less.

The study also found that the majority of U.S. adults, 71 percent, identify as Christian. Further, it found that the trend holds across multiple Christian traditions, such as Evangelical Protestants, mainline Protestants, historically black Protestants, Catholics, and Mormons. Specifically, “the propensity for highly educated Christians to exhibit relatively high levels of religious observance is most pronounced with respect to religious attendance.”

Looking at the U.S. as a whole, however,

Among all U.S. adults, college graduates are considerably less likely than those who have less education to say religion is “very important” in their lives: Fewer than half of college graduates (46 percent) say this, compared with nearly six-in-ten of those with no more than a high school education (58 percent).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

At the same time, Americans with college degrees are no less likely than others to report attending religious services on a weekly basis. Roughly a third of U.S. adults with college degrees (36 percent) say they attend a house of worship at least weekly, about the same as the share of those with some college (34 percent) and those with a high school diploma or less education (37 percent) who say they attend services once a week or more.

Indeed, fully three-quarters of college graduates are affiliated with some religion (including 11 percent who say they are adherents of non-Christian faiths like Judaism, Hinduism, Islam and Buddhism), as are 76 percent of those with some college experience and 78 percent of those whose education topped out with high school.

Among the U.S. adults who describe themselves as nonreligious, the study shows that “those who have college degrees are considerably less religious than ‘nones’ without a college education.”

Highly educated Jewish people also tend to be less religious than those without a college degree. “These differences are driven partly by Orthodox Jews, who tend to be much more religiously observant and less educated.”

Finally,

There is no clear pattern when it comes to the relationship between religion and education for U.S. Muslims… Muslims with a college education and those with no more than a high school education attend mosque and pray at about equal rates: Roughly half of Muslims in both of these educational groups attend services at least once a week, while twothirds pray some or all of the five salah (Islamic prayers) each day. Nearly all Muslim Americans in each educational category (95 percent each) say they believe in God.

[…]

Hindus are not included in this analysis of religion and education because the vast majority of Hindus in the U.S. have college degrees.

The study states that it is not seeking to explain why these patterns exist, just that they do. Though the study did not compare these results to previous ones, it does note that “the idea that highly educated people are less religious, on average, than those with less education has been a part of the public discourse for decades.”—Cyndi Suarez