July 1, 2020; Guardian

Over the course of the coronavirus pandemic, more than 36,000 meat processing and factory farm workers in the US have tested positive for COVID-19. According to a tally by the Food and Environment Reporting Network, over 128 have died. So why is North Carolina closely guarding testing data from meatpacking plants as deaths and hospitalizations rise and complaints of lack of personal protective equipment escalate?

“Why, when a nursing home has an outbreak, it’s in the paper, but when a meatpacking facility does, it’s not?”

That is what Rev. Mac Legerton, a longtime grassroots policy advocate and co-director of the Robeson County Cooperative for Sustainable Development, would like to know. Legerton is among those who have been publicly critical of North Carolina’s failure to inform the public of health risks in rural meatpacking plants.

To Legerton’s point, even in the early days of COVID-19, outbreaks at nursing homes were not only widely reported, but fines were assessed and threats of federal funding were publicly touted. As of April 2nd, Life Care Centers of Kirkland faced over $600,000 in fines for their handling of an outbreak. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service (CMS) issued fines of over $13,000 per day—and this was in March, the early days of the outbreak. It was that very outbreak in the upscale Seattle suburb that put the coronavirus on the radar for many people. Arguably, we know better now and should be able to react quickly to save resources and lives.

It is not just state government that Legerton and his nonprofit cohort feel is missing-in-action on this issue. He would like to know why local government and the media have looked the other way.

In the age of COVID-19, knowledge is power. One of the sought-after and oft-reported pieces of information is who those infected have come into contact with and where emerging epicenters are. In this context, withholding such information is a dereliction of duty.

As for the media, they’ve reported on birthday parties and choir practices that flouted CDC guidelines, but often ignore the risks that essential workers outside of healthcare face. When Washington socialite Ashley Taylor Bronczek threw a dinner party to celebrate a successful fundraiser for the Washington Ballet and then tested positive for COVID-19, a few hours later, it was a gaffe covered by the Washington Post and People Magazine. Legerton would respectfully argue that if you drive further south on the I-95, there is a health-and-safety catastrophe that likewise merits attention.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The company in Legerton’s crosshairs is Case Farms. No stranger to controversy, Case Farms has repeatedly been cited for abuse of animals and exploiting a desperate immigrant labor force with few options for work and even fewer options when catastrophe strikes at work. Overall, undocumented immigrants are less likely to report problems and abuse or join unions. In 2015, Case Farms’ OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) fines topped $1.4 million after workers lost legs and fingers.

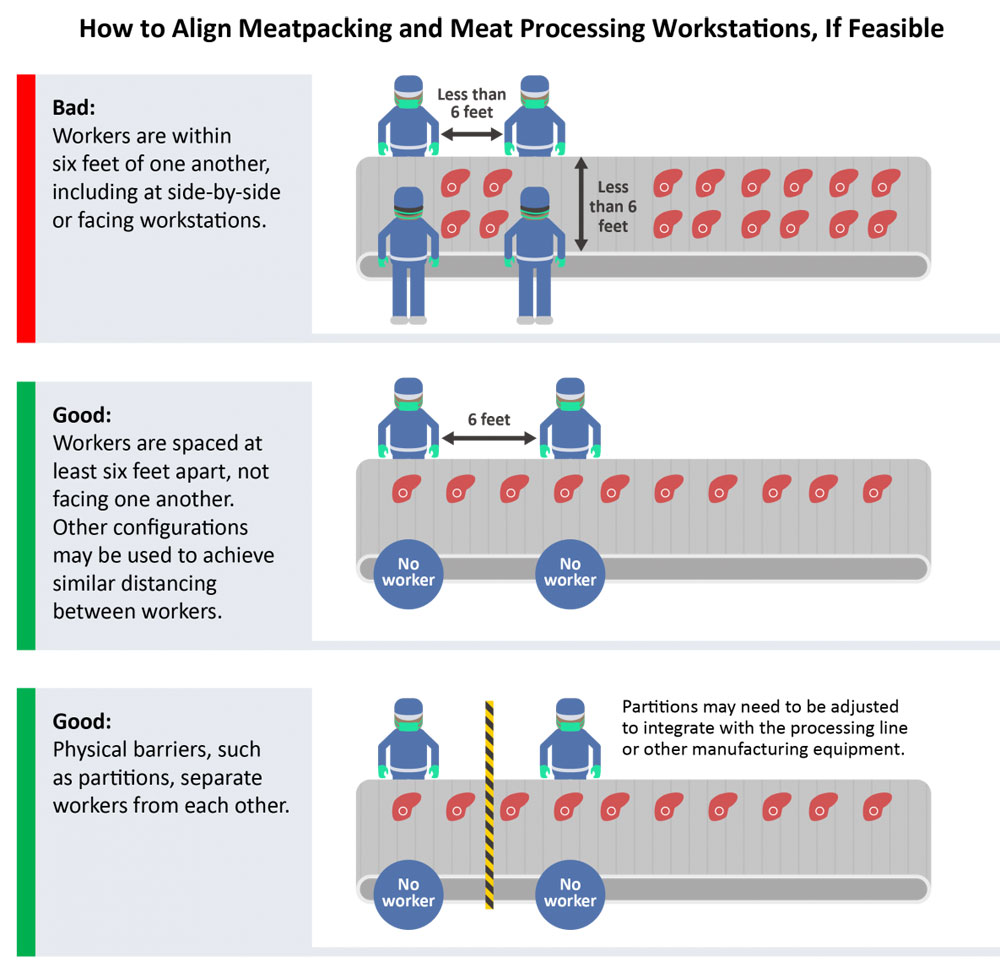

Unlike other producers who paused production to implement safety standards and testing protocols, Case Farms, has failed to provide distance between work stations or proper protective equipment. When they did conduct widespread employee testing in June, the information was closely guarded and not released to the public.

The Guardian reports on a cozy relationship between the producers and the local health department that certainly was not prioritizing public safety. On June 8th, the health department for Burke County, where Case Farms’ facility is located, reported 136 new COVID cases, a 25-percent increase in its total caseload. Yet neither the company, county officials, nor the North Carolina department of health and human services would confirm whether those cases were connected to Case Farms.

Confirming they have the data, but are choosing not to release it, Burke County health department spokeswoman Lisa Moore states, “We know where they are, but we are not a county that can divulge every place where they are.”

This extends far beyond an economic issue. Something deeper seems to be at play. While far from picture perfect, other plants like Tyson Fresh Foods paused production to implement stringent testing procedures designed to support employee wellness while maintaining production.

Particularly in current times of a mass reckoning of the systematic abuse of people of color, we cannot ignore facts that were well established pre-COVID, including who usually works in slaughterhouses. According to a 2017 report from Bloomberg Businessweek’s Peter Waldman and Kartikay Mehrotra, roughly a third of America’s workers in the meat industry are foreign born and non-citizens.

Wading through blood and guts, being at risk for loss of limbs and life, these are just part of the daily grind in meat production. This isn’t hyperbole; the injury rate in a slaughterhouse is about three times higher than a typical American factory. The sanitation crews at meatpacking plants fare even worse than the production staff, with exposure to chemicals and risk of injury or death from heavy machinery sometimes left operating to expedite the sanitization process and limit production disruption. For now, it appears a lack of response to COVID-19 is also in the mix.—Carrie Collins-Fadell