October 30, 2019; Hyperallergic

Last month, the Poeh Cultural Center in New Mexico opened a new exhibition that to the region’s Pueblo communities represents a significant homecoming. The exhibit opened on indigenous people’s day, October 12th. The 100 works of Tewa pottery—now on display in the museum, located on Pojoaque Pueblo land about 15 miles north of Santa Fe—were carefully selected from a collection at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC. As described on the Poeh website, “After a century-long and epic journey, this sacred ancestral pottery will be reunited with the descendants of the creators.”

Writing for Hyperallergic, Ellie Duke notes that the new exhibition, titled “Di Wae Powa: They Came Back,” is only one aspect of an emerging partnership between the two cultural organizations. In 2015, leaders from the Pojoaque Pueblo proposed to NMAI that the Washington museum return the more than 500 Tewa pottery pieces in its collection to their communities of origin. The 100 pieces now on display at the Poeh Cultural Center represent a long-term loan from NMAI, although no timeline has been set for their stay in New Mexico. The arrangement is described as a “co-stewardship,” one in which both institutions—and their respective constituents—are likely to learn from each other. For example:

- While NMAI staff will advise Poeh staff about conservation, local Tewa potters will help NMAI to better understand the origins of the pieces and the various techniques and styles for how they would have been made and used within the Pueblo communities.

- The Tewa pieces on display help NMAI to achieve one of its goals “to connect native peoples with their material heritage,” according to Cynthia Chavez Lamar, Assistant Director for collections at NMAI. At the same time, the exhibition serves as a “teaching collection” at Poeh, allowing local potters to “examine and work with certain pieces directly,” and to use them to educate new generations of Pueblo People about their pottery-making traditions.

The Hyperallergic article explains that the 100 pieces on display at Poeh were selected by representatives of the six Tewa-speaking Pueblos—Nambé, Pojoaque, San Idelfonso, Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clare, and Tesuque. All of the pottery selected was utilitarian, not ceremonial; all of the pieces had been sold, rather than being excavated. Poeh executive director Karl Duncan explains, “We want to make sure that the exhibit, this space, felt welcoming and comfortable to Tewa Pueblo visitors.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

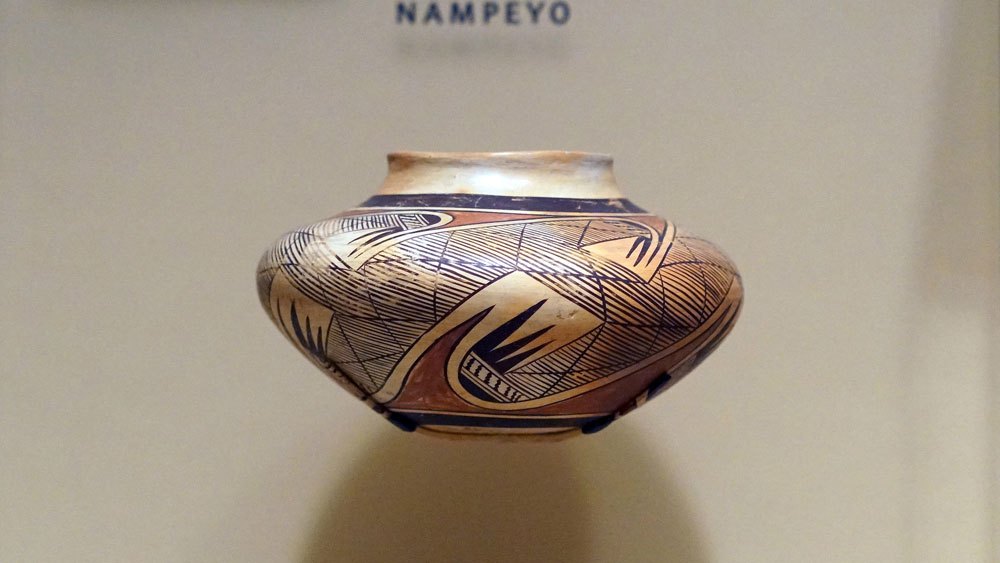

A short video on the Poeh website about the Tewa pottery underscores the spiritual nature of the artistic process behind making these pieces. As explained by Evonne Martinez of San Idelfonso Pueblo, “It’s not just a piece of clay, it’s not material. It’s what you put into it from your heart and mind. It’s the song, it’s the prayer, it’s the conversations that took place when they were being made.”

The Poeh Cultural Center, established in 1988, is described on its website as “the first permanent tribally owned and operated mechanism for cultural preservation and revitalization within the Pueblo communities of the northern Rio Grande Valley.” As noted in the Hyperallergic article, the culture of those communities “was systematically wiped out in the 16th century,” and “Tewa pottery became an important method of cultural practice and resistance after the Spanish arrived.” For many 21st-century residents of these Pueblos, the Tewa pottery is much more than artwork that has come back home; it carries the spirits of their ancestors, and so bringing these treasured pieces back to Northern New Mexico is an act of communal restoration. –Eileen Cunniffe