February 26, 2014; Bill Moyers

Among liberals and progressives, the essay of University of Pennsylvania political science professor Adolph Reed in the March 2014 issue of Harper’s has stirred tons of debate. Reed’s argument is clear from the essay’s headline: “Nothing Left: The Long, Slow Surrender of American Liberals.” Bill Moyers interviewed Reed late last month, eliciting additional thoughts from the professor that, in Moyers’ words, about “the notion that liberalism is flying the white flag of capitulation.”

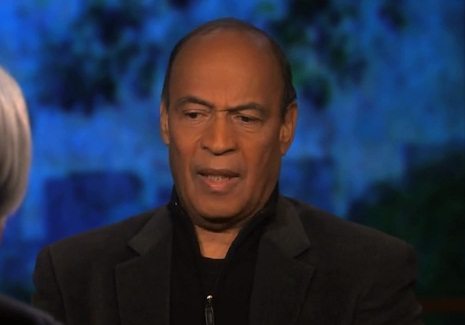

Reed’s own articulation of his analysis needs little or no embellishment:

Adolph Reed: I mean, there are leftists around, certainly. There’s no shortage of them. And there are left organizations, and there are people who publish left ideas and kind of think left thoughts. But as a significant force that’s capable of shaping the terms of debate in American politics, you know, the left has gone and has been gone for a while.

Reed: You know, working people in America got more from Richard Nixon than we got from Clinton or Obama…. The labor movement and what has since been called the social movement of the ‘60s were dynamic enough forces in the society that even Nixon, who called himself a Keynesian, felt that there was a need to respond to them. So that’s how we got occupational health and safety, affirmative action, like other stuff.

Reed: How do we go about building the broadly based, mass movements that we need to try to have some effect on changing the terms of political debate, right? I mean, I’m a realist about this. I think that’s what the goal has to be for the rest of my lifetime anyway.

Reed: I’d say the first step has to be a focus on changing the terms of political debate. Because we’ve got to be able to put…the issue of economic inequality, back on the table. I mean, even you know, the Democrats who raise it tentatively and back away as soon as they do.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Reed saves his strongest criticisms for President Obama, such as these comments from his article in Harper’s:

Obama and his campaign did not dupe or simply co-opt unsuspecting radicals. On the contrary, Obama has been clear all along that he is not a leftist. Throughout his career he has studiously distanced himself from radical politics. In his books and speeches he has frequently drawn on stereotypical images of leftist dogmatism or folly. When not engaging in rhetorically pretentious, jingoist oratory about the superiority of American political and economic institutions, he has often chided the left in gratuitous asides that seem intended mainly to reassure conservative sensibilities of his judiciousness…. This inclination to toss off casual references to the left’s “excesses” or socialism’s “failure” has been a defining element of Brand Obama and suggests that he is a new kind of pragmatic progressive who is likely to bridge—or rise above—left and right and appeal across ideological divisions.

Obama also relies on nasty, victim-blaming stereotypes about black poor people to convey tough-minded honesty about race and poverty…. Indeed, even ersatz leftists such as Glenn Greenwald, then of Salon.com, and The Nation’s Katrina vanden Heuvel defended and rationalized Obama’s willingness to disparage black poor people. Greenwald applauded the candidate for making what he somehow imagined to be the “unorthodox” and “not politically safe” move of showing himself courageous enough to beat up on this politically powerless group. For her part, vanden Heuvel rationalized such moves as his odious “Popeye’s chicken” speech as reflective of a “generational division” among black Americans, with Obama representing a younger generation that values “personal responsibility.”

In the end, Reed takes on the politics of the American left and pronounces it dilettantish. Again, quoting the Harper’s article:

If the left is tied to a Democratic strategy that, at least since the Clinton administration, tries to win elections by absorbing much of the right’s social vision and agenda, before long the notion of a political left will have no meaning. For all intents and purposes, that is what has occurred. If the right sets the terms of debate for the Democrats, and the Democrats set the terms of debate for the left, then what can it mean to be on the political left? The terms “left” and “progressive”—and in practical usage the latter is only a milquetoast version of the former—now signify a cultural sensibility rather than a reasoned critique of the existing social order. Because only the right proceeds from a clear, practical utopian vision, “left” has come to mean little more than “not right.”

The left has no particular place it wants to go. And, to rehash an old quip, if you have no destination, any direction can seem as good as any other. The left careens from this oppressed group or crisis moment to that one, from one magical or morally pristine constituency or source of political agency (youth/students; undocumented immigrants; the Iraqi labor movement; the Zapatistas; the urban “precariat”; green whatever; the black/Latino/LGBT “community”; the grassroots, the netroots, and the blogosphere; this season’s worthless Democrat; Occupy; a “Trotskyist” software engineer elected to the Seattle City Council) to another. It lacks focus and stability; its métier is bearing witness, demonstrating solidarity, and the event or the gesture. Its reflex is to “send messages” to those in power, to make statements, and to stand with or for the oppressed.

This dilettantish politics is partly the heritage of a generation of defeat and marginalization, of decades without any possibility of challenging power or influencing policy

Why raise the Reed argument in a nonprofit journal such as NPQ? With so many nonprofit persons leaning Democratic in election polls, we think Reed’s analysis is terribly valuable for nonprofits to consider. Does Reed make you rethink your feelings about the “neoliberal” Democratic Party and its titular head in the White House?—Rick Cohen