July 9, 2020; Indian Country Today and Crooked Media

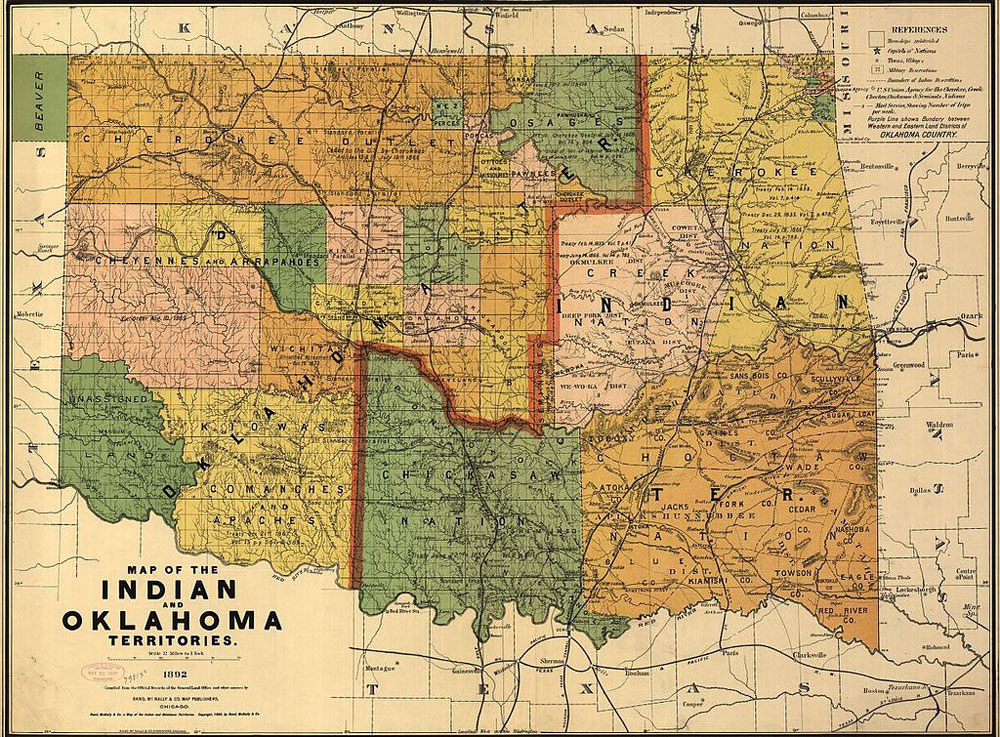

Native nations are celebrating this week after a Supreme Court ruling on Thursday that affirmed tribal sovereignty. In McGirt v. Oklahoma, the court ruled that reservation boundaries established by Congress in the 19th century remain in place, despite nearly two centuries of encroachment. Thanks to this ruling, nearly half the land in Oklahoma is affirmed to be Indian country.

“In holding the federal government to its treaty obligations, the US Supreme Court put to rest what never should have been at question,” said John Echohawk, Pawnee and executive director of the Native American Rights Fund.

Let’s start at the beginning. In 2018, the court heard arguments for Carpenter v. Murphy, a murder trial whose grounds for appeal rested on the fact that the murder occurred on Muscogee Creek land. Thanks to a law called the Major Crimes Act, Native citizens who commit crimes on Native lands can only be tried in a federal court—meaning Patrick Murphy’s conviction and death sentence in an Oklahoma state court was not valid. Oklahoma argued that it had jurisdiction because the reservation no longer existed.

The court declined to issue a decision in 2018, and asked for the case to be reargued in the 2019–2020 session—an extremely rare occurrence, and one that several experts chalked up to the court’s worries about the decision’s implications for non-Native Oklahomans living and working on the land in question.

Instead of deciding Murphy in 2019, the justices granted review to McGirt v. Oklahoma, whose appeal rested upon the same grounds. The SCOTUS Blog suggested this might be because “Justice Neil Gorsuch was recused in Murphy, apparently because he participated in the case as a judge on the US Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, so only eight justices were available to resolve that case. In contrast, a bench of nine can hear argument in McGirt, a significant distinction if the justices deadlocked 4-4 in Murphy.” The McGirt ruling also applies to Murphy. The decision will have implications for five tribes in Oklahoma: Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion, in which he was joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Justice Gorsuch wrote:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise. Forced to leave their ancestral lands in Georgia and Alabama, the Creek Nation received assurances that their new lands in the West would be secure forever…Today we are asked whether the land these treaties promised remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word.

Oklahoma had tried to argue in Murphy that because the state and non-Native settlers had continued to encroach upon Native land and sovereignty, the reservation no longer existed. The most explicit encroachments stem from the 1887 Dawes Act, which split the collectively owned reservation into individual allotments that could be sold within and without the tribes. (The Dawes Act had many terrible repercussions for Native peoples, and Rebecca Nagle’s podcast series This Land explains them compellingly.)

The state went one step further in McGirt; Justice Gorsuch wrote, “Unable to show that Congress disestablished the Creek Reservation, Oklahoma next tries to turn the tables in a completely different way. Now, it contends, Congress never established a reservation in the first place.” The justices rejected this argument, and added, “Even if we were to accept Oklahoma’s bold feat of reclassification, however, it’s hardly clear the State would win this case.”

So, what are the implications?

First of all, it’s important to be clear that the Supreme Court has not “awarded” the tribes any land. (Some senators seem to be confused about this.) The court merely affirmed boundaries that have existed since an 1852 patent. The fact that settlers in Oklahoma have cheated, squatted, and intimidated Native tribes off portions of their land doesn’t reverse an act of Congress. In fact, thanks to leaders John and Major Ridge, the Muscogee Creek Nation is in the unique position of actually owning their land—for most tribes, the US government holds their reservations in trust. (Again, we refer you to This Land for details.) That the court had to step in and affirm the treaties’ application is an indicator of the disrespect with which the US has historically treated its covenants with indigenous peoples, and not a reversal of any prior laws.

Very little will change for non-Native Oklahomans. The tribes can’t kick them off their property, or subject them to Native law, or take away their businesses, even if they wanted to. Muscogee Creek Nation already runs a police force and three hospitals that accept non-Native patients, a critical service in cash-strapped Oklahoma. The Creek government issued a statement, saying, “Today’s decision will allow the Nation to honor our ancestors by maintaining our established sovereignty and territorial boundaries. We will continue to work with federal and state law enforcement agencies to ensure that public safety will be maintained throughout the territorial boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.”

As for Jimmy McGirt, he’s not free to go. As Kolby KickingWoman writes, the ruling “does not mean McGirt’s conviction is nullified, rather he should have been tried in federal court under the Major Crimes Act. He is serving a 500-year prison sentence and could potentially be retried in federal court.”—Erin Rubin