August 18, 2017; Housing Perspectives

Harvard’s Joint Center on Housing Studies (JCHS) has a new report out that captures some trends in the ownership of rental housing in the U.S. The big takeaway from the study is the rapid increase in institutional ownership of rental housing of every size.

Institutional investors own a growing share of the nation’s 22.5 million rental properties and a majority of the 47.5 million units contained in those properties, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s recently released 2015 Rental Housing Survey (RHFS).

While corporate ownership increased across every category of rental housing from single family to developments with more than 50 units, author Hyojung Lee notes a striking feature that jumps out of a comparison of 2015 data with similar surveys done in 2001 and 2012: Institutional ownership of single family and two-four family units jumped dramatically after 2008. Despite the fact that three-quarters of this housing is still owned by individual owners, the yearly data show nearly 50 percent of the acquisitions in these sectors in the 2013–2015 period were by institutional investors. While there’s some reason to believe that some “mom and pop” owners shifted to a corporate structure in this period, that change doesn’t account for the observed growth spurt.

So what? Mr. Lee offers a cautious suggestion that the type of ownership may make a difference for tenants.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Despite potential implications for both renters and the broader housing market, there have been relatively few studies assessing the impacts of changing ownership patterns for rental properties. However, some research suggest that the changes are more than just paperwork. Illustratively, a 2016 discussion paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta reported that large corporate landlords and private equity investors of single-family rental homes in Fulton County, Georgia were far more likely to file eviction notices than small landlords in the county.

Why should nonprofits care? Depending on the scope of the nonprofit’s practice, issues include: adapting to a corporate rental culture, promoting homeownership, and integrating large rental owners and “new renters” into civic planning and development.

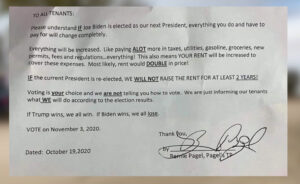

Direct service organizations that are accustomed to calling up local owners to provide stable housing for their clients are likely to find non-local, often anonymous owners with little knowledge of local systems and customs. Just finding a decision-maker in a multilayered corporate ownership entity will be a new challenge for many organizations who work with renters. A recent effort by tenants in Akron to stop hallway harassment by teen family members of a resident involved the state housing finance agency, the local councilman, police, and a fair housing agency all leading to…the corporate owner’s attorney. The attorney, not the local property manager, was the person empowered to address the harassment issue.

Nonprofits that promote homeownership are already facing two dilemmas. The expansion of investor-owned single family homes has reduced the supply of “starter homes” for first-time homebuyers. Moreover, the easy access to single family rental in stable communities has left potential first-time home buyers with the choice of taking on mortgage debt, home repairs, and taxes to live behind a “white picket fence” that they can rent. The single family rental industry is changing the American Dream.

Likewise, for nonprofits engaged in community development activities, the expansion of corporate ownership poses challenges on both sides of the rental equation. On the resident side of the equation, community planners who traditionally reached out to single-family homeowners to help design neighborhood policies and programs should be wondering if single-family renters will join civic associations. Conversely, will resident homeowners continue to support civic associations when most of their neighbors are “short-termers”? On the ownership side of the “rental nation” equation, will absentee corporate owners invest in local planning efforts and contribute to local institutions? Building new engagement strategies may be an urgent need, depending on the growth of corporate ownership.—Spencer Wells