September 10, 2020; NPR, “Shots”

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, middle- and low-income Americans faced financial precarity. Though the job market was hot, too many jobs paid less than a living wage. At the end of 2019, the Brookings Institution released data indicating that almost half (44 percent) of US workers between the ages of 18 and 64 were employed in low-wage jobs earning two-thirds of the median wage or less—a total of 53 million people. How low is low? The median worker in this group earned an hourly wage of $10.22 per hour, or about $18,000 annually (as some worked less than full-time).

Six months into the pandemic, survey data confirm that these low-wage earners are bearing the brunt of the financial pain. In new data from National Public Radio (NPR), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, it’s clear that the financial and health challenges facing families are not evenly distributed.

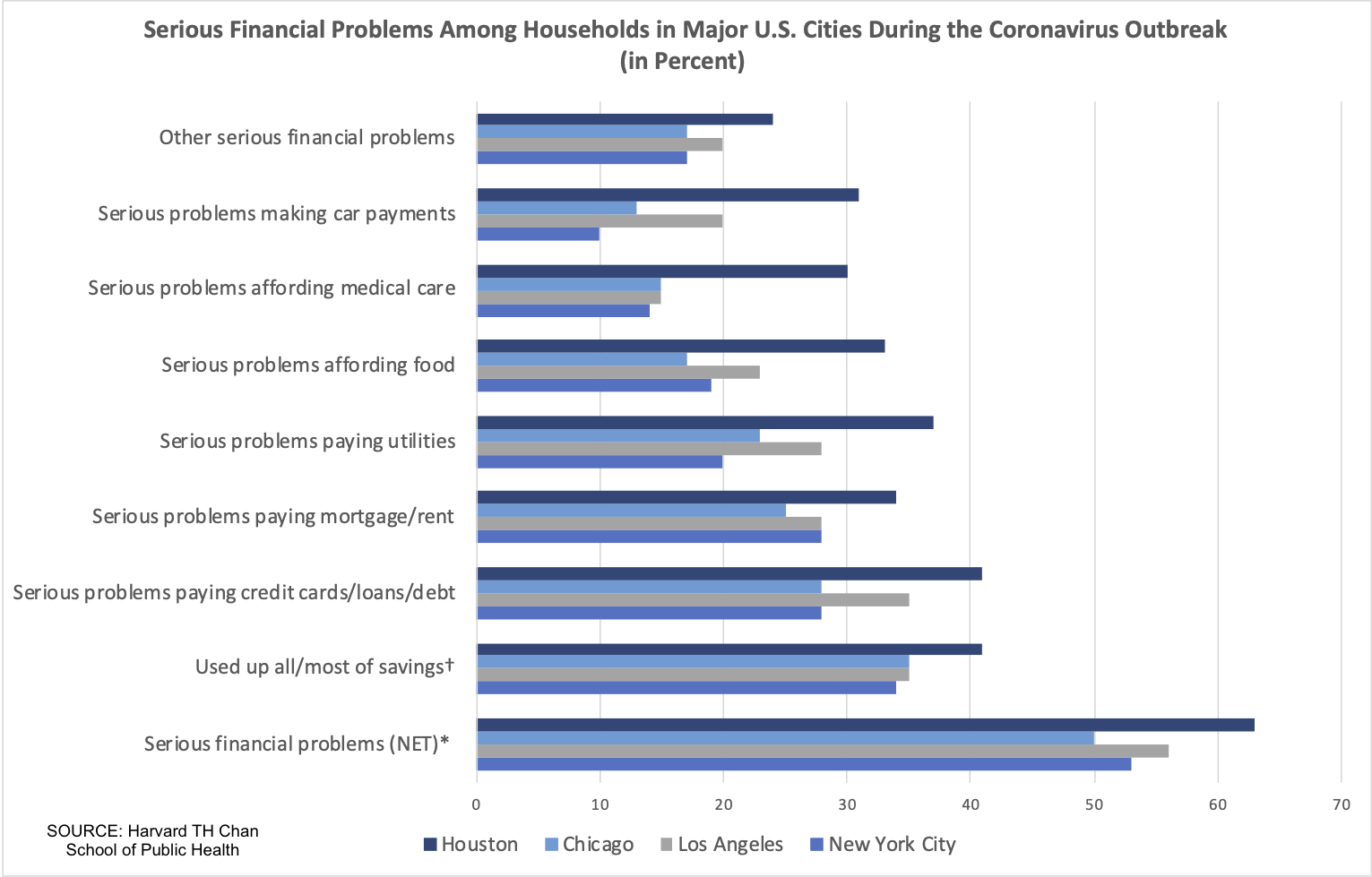

The researchers surveyed households during July and August, collecting national data and targeting the nation’s four largest cities: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Houston. The polling took place before most households would have felt the loss of federal relief programs, including an extra $600 per week in unemployment benefits. Nonetheless, 46 percent of households reported serious financial challenges. For households making less than $100,000, 54 percent reported financial challenges.

In the survey, researchers defined “financially challenged” to include households that had to use up all or most of household savings and/or households that had problems paying major expenses such as a mortgage, rent, utilities, credit card bills, loans, or other debt.

In their first report, the research team unpacks the data for the four metropolitan areas. In each, more than half of respondents reported serious financial troubles. For households of color, with fewer resources to fall back on, the pain was most acute.

For example, in New York City, 53 percent of households reported facing financial difficulties.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- One in three (34 percent) had used up most or all of their savings;

- Nearly three in ten (28 percent) reported problems paying their rent or mortgage; and

- Nearly three in ten (28 percent) had difficulty paying off credit card debt or loans.

Of the 50 percent of New Yorkers who reported having lost a job or income, 73 percent reported serious financial problems. Most significantly, a majority of Latinx households (73 percent) and Black households (62 percent), as well as households with incomes under $100,000 (65 percent) were financially challenged.

Other cities reported similar disparities.

- In Houston, 63 percent of households reported financial distress, with 81 percent of Black households and 77 percent of Latinx households reporting serious financial challenges.

- In Los Angeles, 56 percent of households overall faced financial pain, but 71 percent of Latinx households were facing financial trouble. Of Black households, 52 percent were struggling financially.

- In Chicago, 50 percent of households overall faced serious financial problems, whereas 69 percent of Black households and 63 percent of Latinx households reported financial trouble.

“Before federal coronavirus support programs even expired, we find millions of people with very serious problems with their finances, health care, and with caring for children,” said Robert J. Blendon, co-director of the survey and a professor emeritus at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Blendon told NPR, “I would have expected that all the aid that was coming from various sources would have narrowed, not eliminated, the differences by race and ethnicity.” But the data suggests that the billions of dollars of aid in the CARES Act and other relief programs did not reach many of those most in need of support.

In addition to questions about financial stress, the survey asked about healthcare and caring for children. About 20 percent of households reported difficulty accessing healthcare services during the pandemic. In Houston, where the state of Texas has not expanded Medicaid, one in four households had difficult accessing healthcare. Additionally, about three-quarters of those working in healthcare expressed serious concerns about their safety at work, an indication that healthcare workers still do not have the personal protective equipment they need.

Families with children faced unique challenges. Majorities of households with children in all four cities—New York (60 percent), Los Angeles (69 percent), Chicago (51 percent), and Houston (60 percent)—reported serious problems. Households had trouble keeping their children’s education going, helping children adjust to major life changes, finding childcare while working, and finding space for children to get physical activity while maintaining a safe distance from others.

With school going remote for many, households also express problems with broadband access. At least four in ten households with children are having serious difficulties with their connection or no high-speed internet at all.

As the report authors indicate, “These findings raise important concerns about households’ abilities to weather long-term financial and health effects of the coronavirus outbreak, as a large share have depleted their savings and are having major problems paying for basic costs of living, including food, rent, and medical care.” In short, even as many provisions of the CARES Act that were providing a support layer expire, the case for increased federal support has never been greater.—Karen Kahn