January 23, 2018; The Atlantic

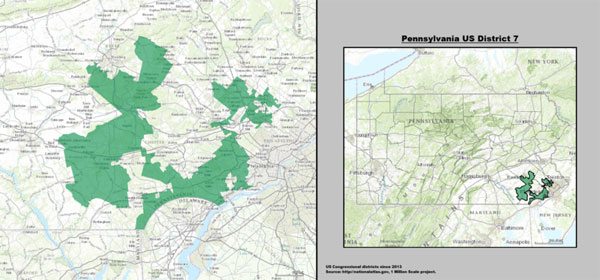

A week ago, NPQ wrote about the decision of the Pittsburgh Foundation to, for the first time in the community foundation’s 73-year history, file an amicus brief in a case before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The case, League of Women Voters v. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, challenged the state’s congressional district map. In its brief, the Pittsburgh Foundation argued that the highly partisan drawing of districts had resulted in a “draconian infringement of the constitutional rights of Pennsylvania citizens.”

CEO Maxwell King said the foundation felt compelled to act out of “concern about the strength of the civic fabric. More and more voters feel as if they don’t matter, they don’t have a role. I can’t think of anything more threatening to the civic strength of the community than that.”

The Court heard oral arguments last Wednesday and ruled quickly. Echoing the Pittsburgh Foundation’s language, the Court found that the state’s congressional district map “clearly, plainly, and palpably” violates the state constitution and ruled in favor of the plaintiffs.

In its vote, the Court followed partisan lines. The Democrats, notes Inquirer columnist John Baer, have a 5–2 majority on the Court due to a successful campaign to elect three Democratic justices in 2014. The Court, reports David Graham in The Atlantic, issued “a short decision Monday, with a fuller discussion to follow; two judges dissented, and a third dissented in part and concurred in part.”

The person who split his vote is Justice Max Baer, a Democrat. Baer, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette explains, agreed that “the district maps were unconstitutional but disagreed with issuing an order to redraw them before the primary.”

In the state’s congressional delegation, Republicans currently have a 13–5 advantage. The decision, assuming it stands, would likely change that. Michael McDonald, a nationally recognized redistricting expert at the University of Florida, predicts that a new map would likely create four or five Democratic-leaning districts.

Graham notes that the Pennsylvania case shares several key characteristics with similar cases currently in federal court in Wisconsin and North Carolina. Graham explains:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

All three seek outcomes that would help Democrats and hurt Republicans. Second, all three argue that voters have been deprived of their rights to free speech, free association, and equal protection by virtue of being targeted for their choice to vote for the Democratic Party, which they say resulted in their being drawn into districts that reduced their voting power. Third, all three represent a new movement toward quantifying the influence of partisan gerrymandering.

Finding a way to distinguish unfair gaming of the system from “normal” favoring of your own party is key. After all, it was just last month when Judge P. Kevin Brobson in Pennsylvania had ruled for the defendants because he said he could not identify where the “line between permissible partisan considerations and unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering” lies.

So how do you draw such lines? Graham explains,

One metric is the “efficiency gap,” a measure of how many votes for a candidate are wasted—either the number of votes in excess of what the candidate needs to win, common when voters backing a candidate are packed into a district, or the number of votes cast for the loser, when that candidate’s supporters are dispersed. Another method of quantifying the impact of gerrymandering is to run random simulations of maps to show how far the existing maps sit outside normal distributions.

Graham observes that, “Either because of that new approach, or because ever-more-creative redistricting efforts have produced maps carved up into fantastical districts that would make Elbridge Gerry himself blush, judges suddenly seem to be more receptive to such arguments.”

In Pennsylvania, the League of Women Voters filed in state court. This means that the ruling is likely to stand, but its influence outside of the state will be limited. Earlier this month in North Carolina, however, a federal court struck down that state’s maps, which Graham notes, is “the first time a federal court had ruled a redistricting plan represented an unconstitutional gerrymander.” The North Carolina case has been stayed by the US Supreme Court, which is already considering a similar Wisconsin case. Graham adds that the US Supreme Court “has also agreed to hear another case, from Maryland, and rejected a case from Texas on procedural grounds.”

There are no new maps in Pennsylvania yet, but the court has set a very short timeline. The state legislature must submit a revised map by February 9th and the governor must forward an approved plan by February 15th. At present, both houses of the Pennsylvania legislature have Republican majorities, but the governor is a Democrat, so any plan approved would need to have bipartisan support. In the event a plan is not submitted by February 15th, the Court could draw its own map. The Court ruling promises a final map no later than February 19th, which is important given that primary elections will take place on May 15th.

In all likelihood, Pennsylvania will be the only state to redistrict this year, but the other cases might well affect elections in 2020, as well as post-census redistricting. Graham cautions, however, that, “If the recent trend holds…judges will be looking over the shoulders of whoever wins in two years, and they will be less willing to tolerate partisan gamesmanship.”—Steve Dubb