Editor’s Note: This article is drawn from Giving USA 2014: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2013 which is published by Giving USA Foundation and is a publication of Giving USA Foundation, 2014, researched and written by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Available at www.givingUSAreports.org.

The Nonprofit Quarterly monitors the nonprofit economy in a number of ways and recently we have been struck by the number of local performing arts organizations that either teeter on the brink of closure or have closed already. Many of these groups have experienced a “perfect storm” through the recession and subsequent recovery, often including the following:

- Capital projects that did not foresee the recession’s effect on giving and local government investments in the arts,

- Reduced audience revenue, and

- Reduced revenue from donors.

All of which occurred over a period of years when reserves were used and debt acquired, resulting in deficits that, by this past year, seemed unassailable.

But as we look at the Giving USA report for 2014, we see a healthy increase of giving for the arts, culture, and humanities. As always, the giving patterns of Americans do not immediately translate to the reality of life on the front lines for many nonprofits.

The macro context of giving patterns, of course, is the intensifying inequality of the U.S. recovery as experienced in the overall economy. According to a Pew study, between 2009 and 2011 the wealthiest 7% got wealthier by a big 28% and the rest of us got poorer by 4%. Let’s put it another way: The aggregate 8 million households in that top 7% saw their wealth rise by an estimated $5.6 trillion, while the 111 million households in the bottom group had their aggregate wealth fall by an estimated $600 billion. The wealth of America’s households over this period increased by $5 trillion—an exciting number until we remember that the wealthiest top 7% used to have control over 56% of the pie; now, they have 63%.

So when we look at the headline in Giving USA this year, heralding the fact that, by these estimations, giving has rebounded since the recession almost to its previous peak in 2007, we could be happy—or we could take it with the same grain of salt as with reports that the economy overall has rebounded.

Through these past few post-recession years, we have watched the gap between the very rich and the rest of us increase, so it is unsurprising that to hear that giving has increased as well, but we also need to ask, “Recovery for whom?” Who is it that is giving, and to whom?

Some of this information is too obscured to be able to retrieve immediately, but there may be indicators to help us to see what is happening.

First, the Basics

As most readers will know, giving plummeted during the recession from a record high of $349.50 billion (adjusted for inflation) in 2007 to $298.34 billion in 2009. Since then, it has been climbing back, but relatively slowly. It is now four years into the giving recovery and we have still not yet fully recovered.

In any case, the good news is that in 2013 total giving grew by 3% in inflation-adjusted dollars, with donations rising from $320.97 billion (per Giving USA’s revised 2012 estimate) to $335.17 billion. Sixty-eight percent of that growth, or $9.69 billion, was in individual giving. Giving by individuals is by far the largest portion of the giving pie, so the estimated 4.2 percent increase in that category translated into the lion’s share of the growth. Other sources of giving also grew, with the exception of corporations, which declined a bit.

There were also only a few fields in which growth of funding received was low or stagnant or nonexistent. Contributions to foundations—a fairly volatile area—actually decreased by 15.5 percent. International giving decreased by 6.7 percent, while giving to religion and human services was pretty stagnant.

Surprisingly, the giving to arts, culture, and humanities grew by 7.8 percent, but as we mentioned above, a comeback of giving in this field would also have to include extra capital to make frail organizations whole.

The Issue of Mega-Gifts

My first question of Patrick Rooney, Ph.D., associate dean for academic affairs and research at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, was about any increase in what might be termed “mega-gifts.” I was interested in where they came from and what they went toward, because they can often skew the numbers pretty dramatically.

As Rooney explained, for this year’s calculation, any gift of $80 million dollars or above was considered a “mega-gift,” because gifts this size were large enough in 2013 to affect the rate of change in total giving. These are added to the numbers after general forecasting is done. This year, gifts in that category totaled $4.22 billion, in contrast to last year when they were a mere $1.55 billion. That is an increase in mega-gifts of 172%. The largest proportion of mega-gifts in 2013 was relatively new money, with $3 billion being contributed by living donors and the rest contributed through bequests.

Who Were the Big Givers, and Where Did the Money Go?

The mega-gifts generally came from recognizable sources. Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan gave almost a billion dollars to the Silicon Valley Foundation. (This will, of course be granted out over time.) Michael Bloomberg was the next highest giver at more than $430 million, given to a variety of organizations, followed closely by John and Laura Arnold, who gave $300 million mostly to their family foundation—money which, again, will be granted over time. Pierre and Pam Omidyar gave $230 million, of which $225 million went to the health-related organization founded by Pam Omidyar known as HopeLab.

In general, the largest portion of these mega-gift dollars went to foundations, large health-related organizations, and universities.

Mega-gifts counted in the giving-by-individuals total for 2013 (in billions of dollars)

| Donor(s) | Recipient | Recipient Category |

Amount (in $ billions) |

|

| Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan | Silicon Valley Community Foundation | Foundations |

$0.99 |

|

| Michael Bloomberg | Various organizations | Various |

$0.43 |

|

| John and Laura Arnold | $235.9 million to the Laura and John Arnold Foundation; the rest went to Fidelity Charitable Trust, Baylor College of Medicine, the University of TX Anderson Cancer Center, ACLU Foundation, and the Center for Reproductive Rights | Foundations |

$0.30 |

|

| Pierre and Pam Omidyar | $225 million to HopeLab; Humanity United; the nonprofit arm of the Omidyar Network; and the nonprofit branch of the Ulupono Initiative | Various |

$0.23 |

|

| Sergey Brin and Anne Wojcicki | $187 million to Brin Wojcicki Foundation; $32-million to the Michael J. Fox Foundation | Foundations |

$0.22 |

|

| Paul Allen | $200 million to Paul G. Allen Family Foundation; $5.3 million to the National Philanthropic Trust; $3-million to the Oregon Shakespeare Festival; $6-million to the EMP Museum | Foundations, other |

$0.21 |

|

| Eli and Edythe Broad | Broad Foundations | Foundations |

$0.16 |

|

| John Arrillaga | Stanford University | Education |

$0.15 |

|

| Theodore and Vada Stanley | $132.7 to Stanley Family Foundation; $8-million to the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute; and they gave a total of more than $1-million to other nonprofits. | Foundations, other |

$0.14 |

|

| Anonymous | $141.96 million to the University of S. California |

$0.14 |

||

|

Total Gifts of $80 million and above (rounded) |

$3.00 Sign up for our free newslettersSubscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox. By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners. |

|||

Source: “A Look at the 50 Most Generous Donors of 2013” from Chronicle of Philanthropy (February 9, 2014)

Mega-bequests counted in the giving-by-bequest total for 2013

The four mega-bequests, totaling $1.26 billion, included this year are:

- $750 million from the estate of George Mitchell to the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation

- $212 million from the estate of Jeffrey Carlton to a trust that will become the Jeffrey Carlton Charitable Foundation

- $160 million from the estate of Muriel Block to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University

- $139 million from the estate of Jack MacDonald to Seattle Children’s Hospital (40%), University of Washington School of Law (30%), Salvation Army (30%).

Source: “A Look at the 50 Most Generous Donors of 2013” from Chronicle of Philanthropy (February 9, 2014)

But to take a larger view, one should marry this mega-gift landscape to that of mere million-dollar-plus gifts. According to Rooney, out of the 1,173 gifts totaling $16.9 billion on the 2013 million-dollar gift list, 529 gifts totaling $7.25 billion were given to higher education, 116 went to health-related organizations, and 102 to arts and culture, but the small number (11) of gifts to foundations of a million or more totalled $2 billion, or about 12% of the value of all reported million-dollar gifts in 2013.

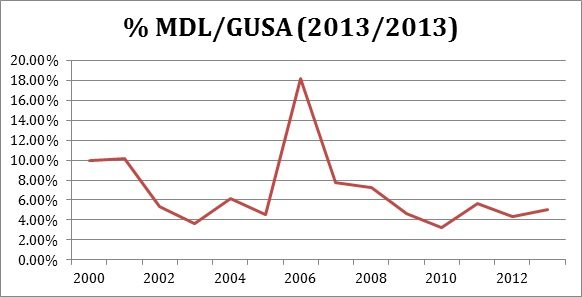

Not all charities report million-dollar gifts, so the proportion is underreported here. On the chart below, however, you can see that the proportion of million-dollar gifts to overall giving is not sharply rising, but is pretty reflective of a post-recessionary year.

| Year | Million-$ gifts as a proportion of giving (per Giving USA) |

| 2013 |

5.05% |

| 2012 |

4.29% |

| 2011 |

5.60% |

| 2010 |

3.28% |

| 2009 |

4.66% |

| 2008 |

7.23% |

| 2007 |

7.75% |

| 2006 |

18.23% |

| 2005 |

4.53% |

| 2004 |

6.12% |

| 2003 |

3.64% |

| 2002 |

5.39% |

| 2001 |

10.20% |

| 2000 |

9.96% |

Note on the numbers above: In 2006, Buffett made his commitment to the Gates Foundation, proving the point that one gift can have a huge effect on the whole scenario.

So why might it feel like the recovery has missed us? There are the usual issues having to do with local economic realities. Most large gifts are given locally, so if you are not in a geographic area that is thriving, you may not feel philanthropically blessed. Additionally, even smaller gifts may be in shorter supply, as Rick Cohen pointed out in this recent newswire about the differences in United Way results this year. He suggested that they were many times tied to the presence of corporations that have too often abandoned ship. (Giving by corporations, by the way, is the only source category that has actually declined.)

Additionally, big gifts tend to go to big institutions—largely in education, health, and arts—and to foundations. Further, when we look at the list of givers on the mega-gift list, many of them represent new money and, with that, self-directed approaches towards change. This is likely to result in a narrower stratum of large grantees in any kind of immediate sense and even possibly over a longer term.

So, What Is the Point?

You can be forgiven if you are not feeling the recovery in a big way.

Some organizations are facing holes that opened up for them during the recession and their access to money from the giving recovery is more limited than the need and debt that was built up over a number of difficult years. Other organizations—in human services, for instance—are not attracting the attention of donors even as they deal with the continuing high human fallout of the recession married in some cases to the reduced coffers of local governments that might normally support them. These kinds of conundrums are everywhere around us.

Giving has recovered in overall terms, but the rich are still giving to big institutions for the most part—and in many cases these institutions are their own programs and foundations. And that mutes the cheering here at NPQ.

This article has been altered from its original form. The rate of giving in 2009 was incorrectly reckoned as $303.76 billion; the correct number has been inserted.