Ray Bradbury once famously quipped that Andrew Carnegie slapped his wallet on rocks and created libraries.1 Too often, philanthropy’s impact on the world is telescoped into an originating gesture and instant gratification. But the changes we see in the world that emanate from great philanthropic insights rarely happen this way; what we see are the big bang end payoffs and not the incremental steps that led to these outcomes, nor the waves of related activities generated along the way.

The #MeToo movement was not built in a day. Marriage equality was the result of a long and iterative effort, with many strategic restarts.

When we celebrate the momentum toward universal access to Pre-K, we need to remember that this too has been the result of years of advocacy and hard work.

We have both played a role in the transformation of public thinking around very young children,2 how they develop and how society can support this development. We think there is much to share in the way this movement came about—information that can inform philanthropy and social movement building. In revisiting this history, we hope to illuminate the critical role that enlightened philanthropy has played as catalyst and nurturer.

A great deal of attention has been paid to the Decade of the Brain, the period from 1990–1999 designated by the US Congress to focus on brain science and its relationship to early development and learning. Advocates across the country used this platform to build national, state, and local efforts to advance child policy. Cover stories in both Time and Newsweek attested to the energy behind the nascent movement. A national campaign waged by children’s hospitals, PTAs, Kids Count projects and hundreds of child-focused nonprofits used the slogan “Who’s For Kids—and Who’s Just Kidding” to make children’s issues more salient during the 1992 election.

But, we believe, it was the potent missing ingredient of the science that made the difference in this era of children’s advocacy, compared to past attempts. This is an oft-overlooked aspect of the early child movement. It happened congruently with the more visible advocacy efforts but stayed largely under the radar screen. It took a large group of scientists many years of collaboration to understand that each area of the brain develops at a very specific time. Some areas of the brain develop prenatally, other areas develop in the first years of life, some areas don’t finish developing until 25 years of age. Even more interestingly, when a particular brain pathway is developing, it is particularly sensitive to environments and experiences.

These important insights owe a great debt to the work of the MacArthur Network on Early Experience and Brain Development (1998–2010), of which one of us (Judy) was a founding member. The MacArthur Foundation had the foresight to invest in cross-disciplinary research to probe the ways in which early experiences “get under the skin” and have a lasting impact on children’s development, shaping who they become, their potential for learning, their perspectives, their motivations and even their health. Without this network and the diversity of scientific studies that the network was built on, we believe much of the early child movement that we celebrate today would not have come to fruition because advocacy would have been ungrounded, uninformed and conceptually disorganized.

This multidisciplinary research agenda cast a wide net, probing both children experiencing the adversity of being reared in Romanian orphanages with little individual attention, and animal studies carefully exposing animals stress at different times during their development. As a result, the network slowly gained a deeper understanding that life stresses impact brain development in very specific ways and that the timing of stress is a critical factor in determining the outcome.

The MacArthur network scientists were able to demonstrate that stress exposure affects brain circuits that are in the process of developing. There is so much brain development going on in the first five years of life that the sheer number of brain circuits strongly affected by early life stress seems astronomical. “Early” matters, but so does “later”—brain architecture continues to develop until about 25 years of age.

So, while this understanding has brought much clarification to the fact that early life experiences have a dramatic impact on brain development, it has also provided the seeds for development of therapeutic strategies targeted at strengthening brain pathways developing in the teenage years. In retrospect, we see that the work of the early brain network did, in fact, influence how we understand development across a wide age span, providing the scientific rationale necessary to empower advocates to overcome the silos of early and adolescent development which have limited coalition building.

In 1999, the MacArthur Foundation doubled down on its initial investment. Fresh from his experience explaining the state of developmental science in Neurons to Neighborhoods (National Academy of Sciences Press, 2000),3 pediatrician Jack Shonkoff joined forces with alumni of the MacArthur network and other scientists to pursue better outcomes in science translation. Frustrated that the political discourse about how to support early child outcomes quickly reduced to unsupported admonitions for individual parents to do a better job and disturbed by unscientific assertions of genetic determinism, Shonkoff and his colleagues decided to adopt a “two-science approach” in which sophisticated social science research was used to help communicate the biological science. One of us (Susan) led this effort to bring multi-disciplinary communications research to bear on the key scientific concepts that the newly formed National Scientific Council for the Developing Child wished to bring to the public and its policymakers.4

An important aspect of this combined effort was critical testing of the concepts within diverse communities, followed by iterative revisions and retesting. FrameWorks researchers went into communities large and small and talked with ordinary citizens about their understanding of early brain development. Working with advocacy groups, FrameWorks established the policy outcomes they would like to see emerge from a deeper understanding of early child development—and built these “high bars” into the communications research outcomes.

Over the decade, more than 30,000 participants would inform the evolving story—rejecting or modifying metaphors, localizing the story to suit their community, identifying holes in the story where the science was not readily available to people, etc. And, as use of the communications research grew, advocates would work with researchers to extend its utility to expand paid leave, change disciplinary policy, reform criminal justice policies affecting incarcerated parents, create programs for children in conflict zones and explain the long-term impacts of adverse childhood experiences.

But these impacts were still far in the future when MacArthur Foundation Vice President for US Programs Julia Stasch let it be known that this was an experiment worth watching and funding, with implications across its grantmaking portfolio. The result was a “Core Story” of early child development—a set of values, metaphors, and principles that, when woven together in messaging, have the empirically demonstrated ability to broaden public conversation about children’s development and open up space for consideration of science-based policy solutions. It was an explanatory story, documenting how brains get “built” over time through the “serve and return” of child-parent interaction which, when broken, or when overwhelmed by environmental stressors, disrupts the normal course of development, with often disastrous and long-term impacts on the child. The new Core Story filled in the “how” that had been missing for too long from advocates’ policy prescriptions.

That Core Story has gone on to be adapted in communities as different as Jacksonville, Florida and Boston, Massachusetts. Entire states (Tennessee) and provinces (Alberta, Canada), as well as national campaigns in Australia, Great Britain, and South Africa have all worked off the narrative outline. In each place, FrameWorks researchers and local advocates have worked together to tailor the story to local views and needs, but the basic explanatory story—what develops, what promotes it and what impedes it—has held up across these geographical divides. In these communities, advocates have been able to quickly grasp the story, adapt it to suit and teach it to their colleagues and their constituencies. And, in many cases, it has been the fact that the new story is “science informed”—both by the neuroscience of development and by the communications science of public engagement—that has encouraged and inspired advocates to have another go at their public officials.5

And the world of science has been affected too. Looking back to the initial group funded by the MacArthur Foundation, it is possible to document not one or two innovations, but dozens of them, with impacts on everything from national policy to family practice. Perhaps best known is the work at Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child,6 where a group of scientists has been analyzing data on brain development for the past 15 years and translating the important concepts of developmental neuroscience into explanations that can be clearly understood by legislators and professionals who allocate funds and resources.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

These topics have included understanding how experiences shape the building of brain architecture, the important role of serve and return interactions with adults to guide the activities that shape children’s brain development, and the impact of toxic stress at various times during brain development. Both of us have been part of this work, as have many others who have worked on this iterative process of consolidating scientific understanding in these research areas, testing how to most effectively communicate the science, and learning how these messages are translated within communities to come up with an effective pipeline for taking lessons learned from neuroscience to policies that shape how resources are allocated worldwide to help children develop into our next generation of world citizens.

A quick sampler of these efforts underscores the generative impact of the original philanthropic grant. In Oregon, Phil Fisher is teaching family therapists to help parents see how their interactions with children impact the ability and motivation of children to achieve successful social-emotional development. Chuck Nelson (Boston Children’s Hospital) and Nathan Fox UMD) have worked with children raised in Romanian orphanages, as well as those who were placed in foster care, to study the longer-term consequences of this type of early life stress and its remediation on long-term cognitive, social-emotional and health effects. A series of studies by Pat Levitt (UCLA) and Takao Hensch (Harvard) are defining the cellular and molecular processes by which stress impacts the brain, as well as the mechanisms that determine the timing with which brain circuits undergo the developmental process. At Yale, Linda Mayes has been focusing on how stress response mechanisms in children are impacted by addictive behaviors in parents. Hiro Yoshikawa (NYU) is working with Sesame Street to improve conditions for refugee children by infusing this work with brain science.

Indeed, when the MacArthur Foundation announced its 100&Change7 winners this past year, it was able to reap the benefits of its own science translation investment: Two of the three winners framed their projects in the language of the Core Story of Early Child Development, one of the first products of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child that drew from the lessons learned in the MacArthur Network on Early Experience and Brain Development.

What has allowed them to play off each other, to join in a bigger story despite their diverse arenas of impact, is the unifying narrative in which the MacArthur Foundation invested with the work of the FrameWorks Institute. That is, despite the fact that the seeds of the Early Brain Development Network were far flung, they all carried the Core Story of Early Child Development: that early experiences and environments build brain architecture, that the serve and return of adult-child interaction makes it strong, and that exposure to toxic stress can derail brain development.8 Without this unifying narrative, we doubt that the sum of these activities would have yielded the ongoing momentum of a movement.

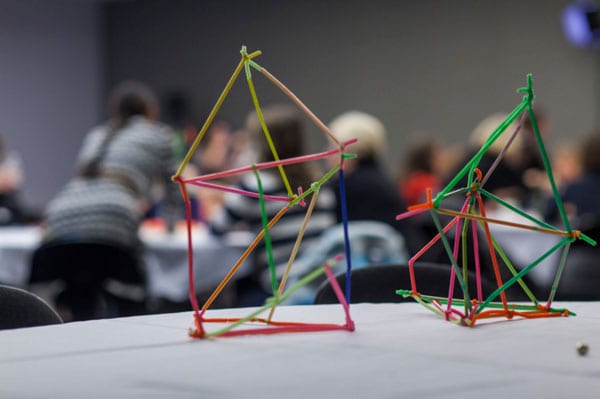

We have seen the Core Story transform a roomful of policymakers, as they played the Brain Architecture Game9 which we helped develop. In this simple game, players work in small groups to build a brain out of pipe cleaners, with straws representing social supports. A roll of the dice determines starting genetics, and life experience cards generate life events that occur as the brain is built. Stresses are represented by weights, as the players work to build a tall brain sufficiently sturdy to withstand the weight of stresses.

Judy has played the game with policymakers in over 25 states and internationally with policymakers from over 30 countries. One of the most memorable statements she recalls is a policymaker whose constructed brain collapsed under the weight of life stresses: “It was not our fault, we just drew some bad cards,” he explained. After a long pause, he acknowledged, “Oh—this is what you are trying to teach us! It is not the kid’s fault, they were just caught in a bad situation, they needed social supports!” The game effectively allows players to have this insight first-hand and to see how imperative social supports are in protecting children from developmental assaults and supporting their trajectory to take up their place as the next generation of citizens. The Brain Architecture Game was funded by Canada’s Palix Foundation, but it built on the MacArthur Foundation’s Core Story investment and has emerged as a very effective means of conveying scientific concepts to the public through the combined efforts of the scientific community and communication science, with testing and iterative input from diverse communities.

Today, there are Core Story projects devoted to uniting policy advocates across issues and ages in a dozen countries, from Australia and Brazil to Peru and South Africa. In all these places, scientists and front-line advocates learn how to explain the process discerned and delineated by the MacArthur network and translated by the FrameWorks Institute into language they can share broadly; working within communities to ensure that the messages communicate effectively in each. After all, a story requires examples and local color to make it come to life. In communities where we have worked alongside advocates to adapt the Core Story, these adaptations have made all the difference.

“You can’t teach brain science to most people,” was a critique we well remember from the early days of our work together. The MacArthur Foundation allowed us the flexibility to contest that conventional wisdom. At best, critics claimed, the impacts will be narrowly confined to academia and will not affect the way people raise their children or policymakers raise these issues with constituents. That critique has now been proven wrong.

One of us (Judy) has first-hand evidence of the impact of this work on some of the poorest communities in the United States. Working for Kids: Building Skills is a new educational program she developed to translate the science of brain development directly to parents, teachers and social service providers using fun, interactive activities and games that are approachable by adults with little education, or low literacy.

In the work Judy does in some of the poorest parts of the country, she has connected with families through Family Support Centers, churches and community centers. Using portable retractable posters of the brain representing what different brain areas do, parents use yarn to build brain pathways, as they think of ways to interest their children in learning skills. They practice the repetitive engagement necessary to build strong brain circuits. Parents answer five true/false questions on a link they can access on their phone, allowing social agencies to track if the program is effectively teaching parents about children’s brain development. These parents are answering questions correctly on average 89 percent of the time. This is a train-the-trainer program, so communities now have their own Working For Kids trainers; thus, a means of teaching each other about how to help children develop sturdy brain pathways. The Core Story of early childhood is proving to be more durable and exportable than anyone could have guessed.

And Judy’s graduate students are discovering how to make science more approachable for families. A new game has been designed by Judy and her students to strengthen brain pathways for communication, cognitive, and social-emotional skills, as well as to strengthen early creativity and science learning. Firstpathwaysgame.com offers 165 age-appropriate activities for parents and children five years and younger.

These new tools are built on the confidence with which scientists now approach their public communications responsibilities. When several moms said they didn’t know enough to interact effectively as teachers to their children, Judy’s graduate students made short 10–30 second videos of parents and children playing the game activities. When parents learned that the brain circuits developing in the teenage years for decision-making, impulse control and multi-tasking can help children combat the effects of early life stress and build future resilience, they asked for activities that teens could do to help strengthen these circuits. Judy’s students went to work and created a new unit of 15 different activities that help preteens and teens develop effective decision-making skills. This product has been tested with youth groups, middle and high schools and even in juvenile detention centers. So, another generation of brain scientists is being inducted into science translation work, listening to what communities need and bringing science to them using communication science based strategies.

No one would have predicted that a popular, community-based tool like Working for Kids would emerge from a group of brain scientists discussing the pre-frontal cortex at the MacArthur Foundation. But that’s what happened, as each of the scientists touched by that experience began to wonder how they could take what they had learned and discussed into more places where people had a need to know about how experiences shape brain development. As a result of their collaboration, they developed a range of new strategies to help us help our children.

These are the building blocks of good philanthropy: being willing to invest in unforeseen outcroppings from a core idea, and to double down at risky but promising moments in the evolution of a movement. And this is the back story behind the movement toward universal Pre-K: how a new narrative about early brain development got infused in the everyday work of dozens of thought leaders who taught it to others and made it the storyline of our time. This is the backstory of the Decade of the Brain. We believe it is a key reason that the work of this decade has endured and continues to influence the way people think about early child development and prioritize it for public action.

Notes

- Pitzer College Commencement Address, June 6, 1976.

- See here for a snapshot of the growth of this movement.

- Harvard(18th ed.) Shonkoff, J.P., & Phillips, D.A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: the science of early child development. Washington, D.C., National Academy Press.

- See Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2014). A Decade of Science Informing Policy: The Story of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Retrieved from developingchild.harvard.edu.

- For a digest of places using the Core Story, see frameworksinstitute.org/hall-of-frames.html.

- See the intertwined history here.

- www.100andchange.org

- A short video using the Core Story of Early Child Development.

- Find out more here.