September 11, 2017; Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

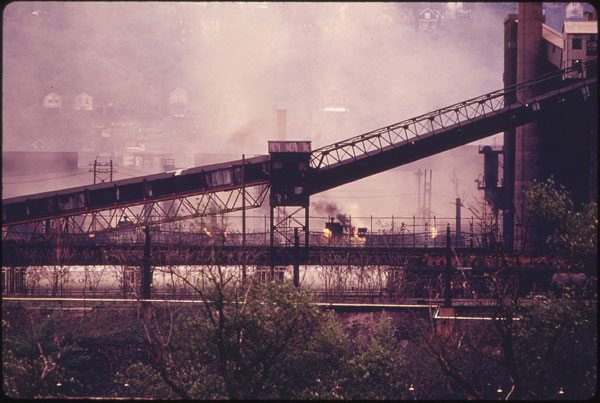

Pittsburgh, once the world’s leading steel producer—they did name the football team the Steelers for a reason—has seen its economy dramatically restructured. In 1901, financier J.P. Morgan paid what was at the time an unheard-of figure of $480 million to purchase Carnegie Steel from Andrew Carnegie and create the U.S. Steel Corporation. Today, U.S. Steel ranks eleventh among Pittsburgh employers. Four of Pittsburgh’s (Allegheny County’s) top ten employers—University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Presbyterian Shadyside, University of Pittsburgh, Western Penn Allegheny Health, and Carnegie Mellon University—are nonprofits. The others are a supermarket, two banks, and government (county, state, and federal). In short, not a manufacturer among them.

Pittsburgh is widely portrayed as a Rust Belt success story of reinvention. And, in some ways, that is true. Yet behind the veneer of a “Pittsburgh renaissance” lies the reality of continued economic inequality. The poverty rate in the city of Pittsburgh remains a high 22.9 percent, compared to 13.5 percent nationally. (Allegheny County, which includes surrounding suburbs, has a lower poverty rate of 12.2 percent.) A recent Brookings Institution report also found a racial divide that is growing at a disturbing rate, with median wages rising by 8.1 percent between 2010 and 2015 in the Pittsburgh region as a whole, even as the median wage for African Americans fell 19.6 percent.

So, if one goal of nonprofits is to address racial and economic inequality, how is the Pittsburgh region’s combined county, municipal, and school tax exemption investment of $300 million a year—which includes a $48 million property tax exemption from Allegheny County and an additional $250 million-plus taken from the coffers of city governments and local school districts—working out? This is a key question posed by Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Rick Lord, who examines the role of the top 50 nonprofits and 14 top private foundations in a 50-mile radius of downtown Pittsburgh.

Lord highlights the rising role of the nonprofit sector in Pittsburgh’s economy. Pittsburgh nonprofits, Lord explains, “employ 1 in 5 workers in the region, control at least one-tenth of its property, and have amassed wealth that far exceeds the remnants of our profit-driven industrial heyday. From UPMC, which has its initials on Downtown’s highest tower, to foundations that give anonymously, their impact is everywhere.”

“They are the economic engine,” Lord adds.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

So, how is that economic power being used? The story is not clear cut or neat, but what is clear is that even though Penn professor Ira Harkavy and Harmon Zuckerman highlighted the rising economic role of “eds and meds” 18 years ago, public policy has yet to catch up with the new economic reality.

An “understaffed IRS,” Lord notes, is unable to fully monitor complicated real estate deals (Pittsburgh-area nonprofits own $12.9 billion in real estate and over $20 billion in total assets), to say nothing of assessing whether the public is getting value for dollar spent (or, better said, tax revenue foregone). Perhaps one of the more damning figures cited by Lord is the finding from a 2014 U.S. Government Accountability Office report that 31 percent of nonprofits whose returns were examined by the IRS “resulted in penalty, revocation or termination of exemption.”

The article also points out that the average top executive salary of the top 50 nonprofits in the Pittsburgh region is $730,000. (By contrast, the median household income in Allegheny County is just above $53,000 and below $41,000 in the city of Pittsburgh.) Top of the list is UPMC president and CEO Jeffrey Romoff, whose current compensation package is valued at $6.99 million. Paying for talent, of course, is the stated rationale for these high salaries, but if nonprofits can afford this level of executive compensation, employ 20 percent of the area’s workforce, and own 10 percent of metro property, what might be appropriate payment to support the city, schools, and county services that support them? In Boston, eds and meds paid $32.4 million in “payments in lieu of taxes” to the City of Boston last year to help finance local city services. In Pittsburgh, Lord reports, the total paid was $400,000.

Lord delves into three case studies to highlight some of the policy questions raised as nonprofits take on a greater role in the Pittsburgh economy. One involves a public-private nonprofit partnership in which $400,000 in public funds was spent per unit of affordable housing created. A second example highlights the struggle of three foundations for 15 years to redevelop the 178-acre Hazelwood coke plant site. A third involves a nonprofit charter school creating a shell nonprofit to skirt state laws forbidding state subsidies to finance charter school construction. Lord also highlights one positive example of a foundation (The Buhl Foundation) using low-interest loans (program-related investment), which has focused on a 20-year, place-based investment strategy in the Northside neighborhood.

Lord’s article doesn’t posit many solutions to the rising nonprofit industrial complex that has emerged. Of course, greater government oversight to ensure fair play would be appropriate, as would be greater nonprofit contributions to local governments—indeed, partnerships with local government might help nonprofits more successfully realize their missions!

More fundamentally, though, it is critical that nonprofits show leadership in stepping up to use their increased economic power responsibly, an approach that is sometimes called an anchor mission. For example, Campus Compact last year persuaded over 450 university presidents to sign onto an action statement that called for their campuses to embrace their “responsibilities as place based institutions, contributing to the health and strength of our communities—economically, socially, environmentally, educationally, and politically” as well as “to challenge the prevailing social and economic inequalities that threaten our democratic future.” Increasingly, nonprofit health care institutions are also seeing investing in the welfare of their surrounding community as an important route to address their own community-serving mission. As a 2015 Initiative for a Competitive Inner City report concludes, “By making valuable and long-lasting contributions to the social, economic, and physical health of their neighborhoods, they’re helping to ensure their own economic futures, as well as the health of their communities.” The potential for nonprofits to leverage their increased economic power, in short, is there. But it won’t happen without maintaining a strong intention to do so.—Steve Dubb