August 2, 2013; International Business Times

In the past few weeks, Congress and the White House have been debating issues concerning college student loans. After several months of haggling, Congress and the White House agreed to limit the interest rate on federally subsidized Stafford loans to 3.86 percent for undergraduates and 5.4 percent for graduate students. The rate on Stafford loans can still rise in the future, and private college loan rates can range from 2.25 percent to 10.125 percent on variable rate loans and 5.75 percent to 12.875 percent for fixed rate loans, according to Sallie Mae sources.

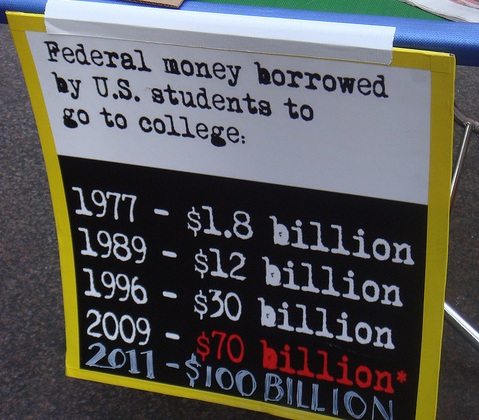

Regardless of the deal limiting interest rates on government-subsidized loans, student indebtedness is a huge drag on the economy and the incomes of college graduates. For the class of 2011, for example, two-thirds of graduating seniors were carrying student loan debt, averaging $26,600 per borrower. Almost 90 percent of lower-income college students receiving Pell Grants also carry loan debt, averaging $24,800 per borrower—about $2,000 more, on average, than graduating seniors with loans. Indebtedness follows students for years: In addition to the 14 million borrowers under the age of 30, there are 10.6 million aged 30–39, 5.7 million 40–49, 4.6 million 50–59, and 2.2 million with student debt over the age of 60. That’s 37.1 million people with student debt, with a total indebtedness between $902 billion and $1 trillion.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

To help students deal with this level of indebtedness, a nonprofit called 13th Avenue Funding, established in 2009, essentially makes equity investments, “financing students the same way venture capitalists finance companies,” that require students to give 6 percent of their income after graduation to the fund for 15 years to pay back what they have borrowed. Six percent might seem high, but it is based on the student-graduate’s employment income and therefore is more affordable during the lower-paid early years of post-college employment. However, for those who don’t meet a stipulated income threshold in their employment after college, or for those who pursue work in programs such as the Peace Corps, the payback is zero. The IBT article suggests that the 13th Avenue concept is meant to help first-generation immigrant college students and low-income students.

How does this differ from a regular loan? Most college graduates, upon entering the workforce, start in lower income jobs but still must pay the required interest on their loans. In this model, they pay a percentage of their income, meaning that while still in entry-level jobs that pay lower wages, they won’t be hit by repayment levels that they cannot afford. Although the model has been endorsed by presidents since Ronald Reagan and has been adopted in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and England, it is still considered experimental in the U.S.

To make this work, the program has to involve more than the students and the 13th Avenue investors. The only entity positioned to verify the student-graduates’ incomes is the Internal Revenue Service. (It’s the same reasoning that’s behind why the IRS has a significant implementation role in the Affordable Care Act, where determination of income levels is necessary for establishing eligibility for ACA health insurance subsidies).

Although 13th Avenue Funding was established in 2009 as a nonprofit, there were no Form 990s available on the Guidestar website, which suggests that it didn’t get its 501(c)(3) ruling until 2012. The 13th Avenue website contains bios of the three principals of the organization, but no financials. It’s not clear from the IBT article when the founder of 13th Avenue, Robert Whelan, and his partners and their spouses put up the initial $165,000 to get the new nonprofit underway, but if it were in 2009, one would have expected to see a 990 filing by now.

The issue of student debt is important to society and to the nonprofit sector. Nonprofits may find themselves hard-pressed to attract graduates when nonprofit jobs don’t pay enough to make loan repayments easy. Making repayments fixed to a percentage of income, and potentially dismissed at low-income levels or when in public service jobs, could be an interesting solution to a societal and sectoral problem. With no real financials to offer in the IBT article or on Guidestar, 13th Avenue Funding needs to provide more information on its website and to public accountability sites to indicate that the model is worth students and the public taking an investment risk.—Rick Cohen