March 19, 2018; News & Observer

NPQ has frequently reported on the well-financed national strategy to privatize schools, on charter school proponents’ misplaced belief that changing schools and teachers rather than focusing on systemic poverty will remedy the racial achievement gap, on charter schools’ accountability, and on the increasingly unusual approach taken by the Waco school board to partner with a community-based nonprofit rather than turn over the school to an outside charter entity.

Our nation’s charter school saga now continues with the launch of North Carolina’s Innovative School District (ISD), a new district created by Republican state lawmakers to take low-performing elementary schools away from local control and cede them to a “qualified” for-profit or nonprofit operator. This move is sparking consequential questions in the state about whether key proponents of school choice are personally benefitting from the new ISD and highlights the stark choices facing poor, rural communities of color when it comes to educating their children.

The possible conflicts of interest revolve around the selection of an organization to operate the schools in the ISD, a decision that rests with the State Board of Education. This past week, the new district’s administrator recommended that the five-year contract go to Achievement for All Children (AAC), a new North Carolina nonprofit with deep ties to the state’s school choice movement. AAC is closely affiliated with the national charter network TeamCFA Schools, founded by the wealthy libertarian John Bryan. Bryan contributed close to $600,000 to N.C. legislative candidates (primarily Republican) from 2011–2016, financially supported the drive to pass the bill that created the Innovative School District, and also donated $50,000 to the political action committee set up to put Republican Lieutenant Governor Dan Forest in office. A fervent charter school supporter, Forest sits on the State Board of Education. “One wealthy Oregonian’s persistent lobbying resulting in the takeover of elementary schools in distressed North Carolina communities is disturbing enough, but to find out his organization may directly benefit makes the whole scheme even more questionable,” said Andrea Verykoukis, spokeswoman for Public Schools First NC, a self-described nonpartisan, nonprofit organization focused solely on pre-K–12 public education issues.

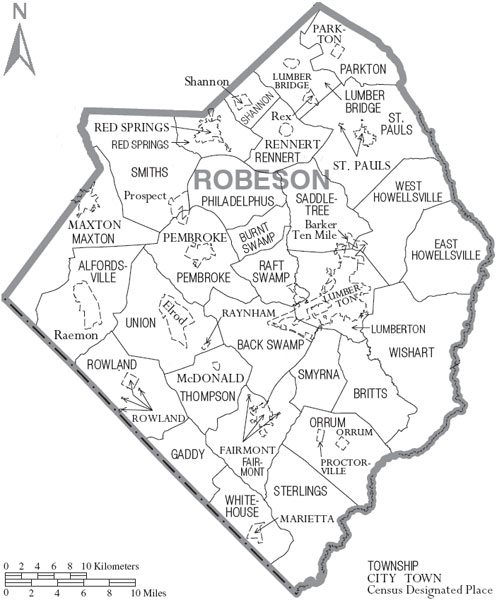

Beyond the potential conflicts of interest is the issue of the dearth of choices facing rural, poor, and minority school districts in the state. The ISD has selected one school to debut this approach: Southside Ashpole Elementary, a school located close to the South Carolina line in one of North Carolina’s most challenged and unique counties. Consistently ranked as the poorest county (out of 100) in North Carolina, Robeson County has a murder rate four times the national average, with young people more than twice as likely as teens in other parts of the state to die before they’re old enough to vote. It is also one of the nation’s most ethnically diverse rural communities with more than two-thirds of its residents American Indian, black, or Latinx. Robeson County is home to the Lumbee Tribe, whose 55,000 members (making it the largest tribe east of the Mississippi) have been unsuccessfully seeking federal recognition (and critical financial benefits) since 1888.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Achievement for All Children, in its proposal for the ISD contract, noted Robeson’s challenges:

Unfortunately, the realities of factory closings, violence, opioid addiction, and obesity have crippled the county to the point that they need outside help to create a path to a successful future. AAC wishes to be of service to create that path and walk alongside them until they reach a time when they can again operate effectively on their own.

At first, citizens vehemently opposed the takeover. In a September 2017 public hearing, members of both the county’s Board of Commissioners and Board of Education unanimously approved a joint resolution opposing Southside’s selection of Ashpole for the state’s ISD. But the commissioners quickly backed out of actually signing the resolution and in January 2018 the school board unanimously approved Southside-Ashpole’s designation. Explained Robeson Commissioner Jerry Stephens, “locals are warming up to the program because they have no choice…Nobody wants the school to close, nobody. They would like another chance to pull up the grades. But it looks like we don’t have enough political clout to change it, so what can you do?”

This local reaction sharply contrasts with that made by local officials in urban North Carolina districts also faced with ISD designation and takeover. In a September 2017 letter to the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, Durham’s Board of Education chairman said that the district is already working “to design and pursue innovative strategies” to improve their low-performing schools and asked that they not be included in the ISD. “(We) strongly request that the targeted initiatives to transform these schools not be derailed by including them in this experiment” and that Durham County residents would not support the “loss of local control” if the ISD took over any of their schools. Urban Durham was taken off the short list while rural Robeson’s Southside-Ashpole is now the guinea pig for the state’s Innovative School District, likely to be run by an entity whose primary donor helps fund the state’s school choice politicians.—Deborah Warren