When Caroline Levine, author of Forms, came to Edge Leadership for an online conversation, we focused on the four forms in her book: whole, hierarchy, network, and rhythm.1 At the end of the conversation, another related but distinct form found its way in: binary. Those last couple of minutes were among the most provocative for me, the genderqueer who feels most at home with nonbinary thinking. Levine commented, “The binary is a very seductive form, but we don’t have to go there.”

In the creation of liberatory structures, it is worthwhile to consider where else we might go instead of turning to binaries. Cyndi Suarez, author of The Power Manual, suggests the future is about choice and multiplicity—getting beyond the fetish of agreement, which so often expresses in binaries: yes or no, right or wrong, with us or against us.2

Chiming in with the yes/and, Kenneth Bailey, author of Ideas Arrangements Effects: Systems Design and Social Justice, added, “At least look at what the binary does, what it affords.”

In Forms, Levine details the lure of binary oppositions, particularly the ones organizing our cultural and political experience, such as masculinity and femininity, public and private, mind and body, black and white. Levine charts the post-structuralist thinking in the 1970s, which spotted that such binaries are covertly hierarchical—a marked pivot from the dominant belief, which persists to this day, that they are neutral: a fact of life. She cites the philosopher Elizabeth Grosz to explain the relationship:

Dichotomous (binary) thinking necessarily hierarchizes and ranks the two polarized terms so that one becomes the privileged term and the other its suppressed, subordinated, negative counterpart.3

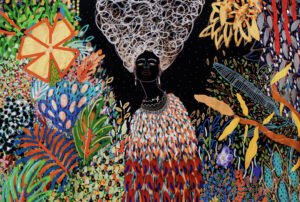

Perhaps Our Path to Liberation Is Through: Beyond the Gender Binary

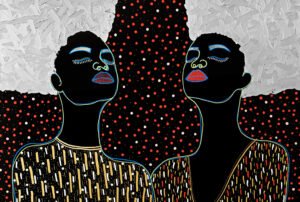

Let’s take a look at one of the most closely guarded binaries: gender. The gender binary is the hierarchical system of classification in which people are categorized as being either male or female. It is important to reinforce that the purpose of this inquiry is not to argue that this binary doesn’t exist, or that it doesn’t have joyful affordances. Clearly it does for many. Indeed, it is so comfortable for some people that the idea of letting it go puts them on the defensive, arguing it is essential.

Today, the gender binary is helpful to discussing the global plight of women, especially when we are talking about the lack of basic human rights afforded in this binary to the women of the world. The binary helps bring clarity vis-à-vis the impact of patriarchy on women, such as lack of access to leadership positions, equal pay, education, and sufficient healthcare.

But this binary—the either-male-or-female-gender thought experiment—accommodates violence against women and trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming people, particularly amplified when layered with a racial hierarchy that devalues anybody not passing as white.

Not even slightly neutral, this binary is a dominance hierarchy. As we gather in the spectrum of gender affinities, we can also imagine a reality where no binary is a society’s key organizing principle.

In his workshop “Post-patriarchy Futures,” Lawrence Barriner II describes the need for men in particular to go “back in time to the earliest roots of your patriarchal conditioning and catapult yourself forward in time to meet and shape your beautiful and whole post-patriarchal self.”4

Barriner’s choice to describe wholeness hearkens back to Audre Lorde when, in “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” she calls the erotic “a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feelings.”5 She describes how patriarchy has controlled and suppressed this resource, particularly through placing the erotic in binary relationship with the pornographic. Lorde redefines pornography, which “emphasizes sensation without feeling”—an objectification, not to be confused with erotic energy, which provides purpose. She conveys the erotic as essential and available through connection and belonging.

Until there is no longer a hierarchical power arrangement that subjugates women, the gender binary does certainly exist, and with consequences. What seems lost in present conversation is the understanding that it is just another malleable form, not an essential truth. Levine weaves in Judith Butler’s thinking:

Gender is the mechanism by which notions of masculine and feminine are produced and naturalized, but gender might very well be the apparatus by which such terms are deconstructed and denaturalized. Indeed, it may be that the very apparatus that seeks to install the norm also works to undermine that very installation.6

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The binary creates structure for men, women, queer folks, and many others to discover ourselves. It’s important, however, to remember that this binary is a blunt instrument being used to organize subtle, complex beings.

Perhaps our path to liberation is through.

Lorde’s thinking about the erotic feminine power can be distinct from the separate thought arrangement where gender is dependent on notions of biological sex. Transgender and other realities are presently sanctioned in most of society, harming those who just might be the most advanced in human evolution, and who have the greatest breadth of access to this energy. The tent women pitch is one that can hold this multiplicity, but it breaks when it no longer holds what is queer. Queerness solves for the status quo, which limits our potential. That queer offering gets crushed when a group relies too much on the gender binary as a passcode for belonging.

Lorde suggests that the erotic is an untapped resource for our purpose, speaking specifically to women in the context of patriarchy. Building on her assertion, I wonder, is this energy available to everyone through practices presently organized as feminine? I think of the erotic as energy which cannot be contained. It is a repressed but thriving force that is perceived to be dangerous by those seeking its control because it disrupts their power story. Come hither energy is infectious. It is gentle like a whisper. It shatters and roars. It commands us, and it demands of us a different way of relating to the sensations of joy and freedom in our bodies. Lorde writes:

The erotic has often been misnamed by men and used against women. It has been made into the confused, the trivial, the psychotic, the plasticized sensation. For this reason, we have often turned away from the exploration and consideration of the erotic as a source of power and information, confusing it with its opposite, the pornographic. But pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling.7

The possibility of liberation in our lives via erotic energy is also described as dangerous for those who hold it, because of the violence that women and trans people experience in society. “I am familiar with the fear that comes up,” said Kalia Lydgate, cultural strategist. “For me it’s in the context of men and the harms they can cause me, but there are so many more layers to it than that.” There is important work men are doing to reduce harm, and so too the possibility that this energy is within them, not just for them to hold or control.

Overcoming the gender binary to be in our complete power requires embracing complexity and creating environments of connection and belonging. This energy is a balm, a drug, a lover who knows better than us what is needed. While the practices to access this may well be held in the present-day feminine, I believe this energy which cannot be contained is genderless.

What a controversial notion—that we can be more than the archetypes that came before. A more blended, nuanced version of the best human qualities—or perhaps wild dimensionality. The possibilities for what comes next are endless. If we’re talking about being innovative, wouldn’t we look to the edges? To the anomalies? To imagine what would happen if we “let it go”? Recently, in conversation, a friend and I were trying to understand power dynamics using the masculine/feminine polarity—and it wasn’t working because we have too many dimensions. We let the polarity go and began having the same conversation through the form and characteristics of the Chinese elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water). All of a sudden, the conversation burst open. Different form, different possibilities—particularly when, as Suarez suggests, a form holds multiplicity.

In the Netflix series Abstract: The Art of Design, toy designer, play expert, and educator Cas Holman describes in great detail how her queer identity supported the development of her craft. She explains that one of the goals of her toys is to get kids “thinking beyond the archetypes.” It’s not surprising to see queer people in roles that involve figuring out how to transform things that are boring, decided, and predictable into things that are full of possibility and life. We’ve had to do this to survive. It’s our expertise.

Anyone can release what they have been told about their gender and instead learn how to pay attention to and find ways to express that energy which cannot be contained—a much bigger, freer, and more luxurious life-force energy that shows us how to obey the laws of nature.

Notes

- Caroline Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (New Jersey and Oxfordshire, U.K.: Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Cyndi Suarez, The Power Manual: How to Master Complex Power Dynamics (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2018).

- Levine, Forms.

- Lawrence Barriner II, “Post-patriarchy Futures,” workshop, spring 2021.

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984). Originally delivered as a speech at the Fourth Berkshire Conference on the History of Women at Mount Holyoke College in 1978.

- Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (New York and London: Routledge, 2004).

- Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.”