September 18, 2020; Boston Globe

It’s often unsettling to confront new knowledge and see our world in new ways. When our ordered paradigms are found to be less true than we thought, we are cast adrift in a chaotic reality. Consider Galileo and others like him when they found the earth was not at the center of the universe but just one of many bodies orbiting around one of many stars. Or, reflect on the United States when the theory of natural selection in evolution reached our shores.

That’s the situation where we now find ourselves, as we recognize that the history of the United States is not as we have constructed it over centuries. For schools and teachers, these moments of change are particularly potent. Do they reject this new lens as heresy—“fake news,” if you will? Or do they recognize the critical value in preparing students to live in the world as it is?

A recent story by the Boston Globe’s Deanna Pan spotlighted teachers, administrators, and school boards that have stepped forward, embraced a new understanding of history, and are now doing the difficult work to reshape their lesson plans and teach differently.

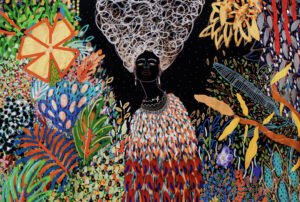

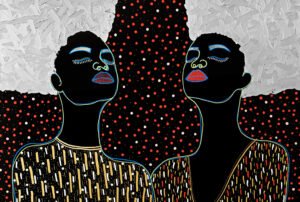

Joana Chacon, a high school English teacher, was ready to broaden the array of literature her students would be asked to take on to reflect a reality that was not driven by white, European authors. Recognizing that this does reflect a fuller picture of literature and the nature of our American culture, she told the Globe she takes “issue with the criteria being used to say some things deserve to be in the canon and some things don’t.”

“The works we regard as ‘classics,’” Chacon says, are “overwhelmingly white, male, and Eurocentric. It’s doing some harm to the souls of our students who are Black, indigenous, and people of color, and it’s honestly doing harm to the souls of all our students.”

In the end, she asks, “We’ve been doing it a certain way for so long. Why not give this a chance?”

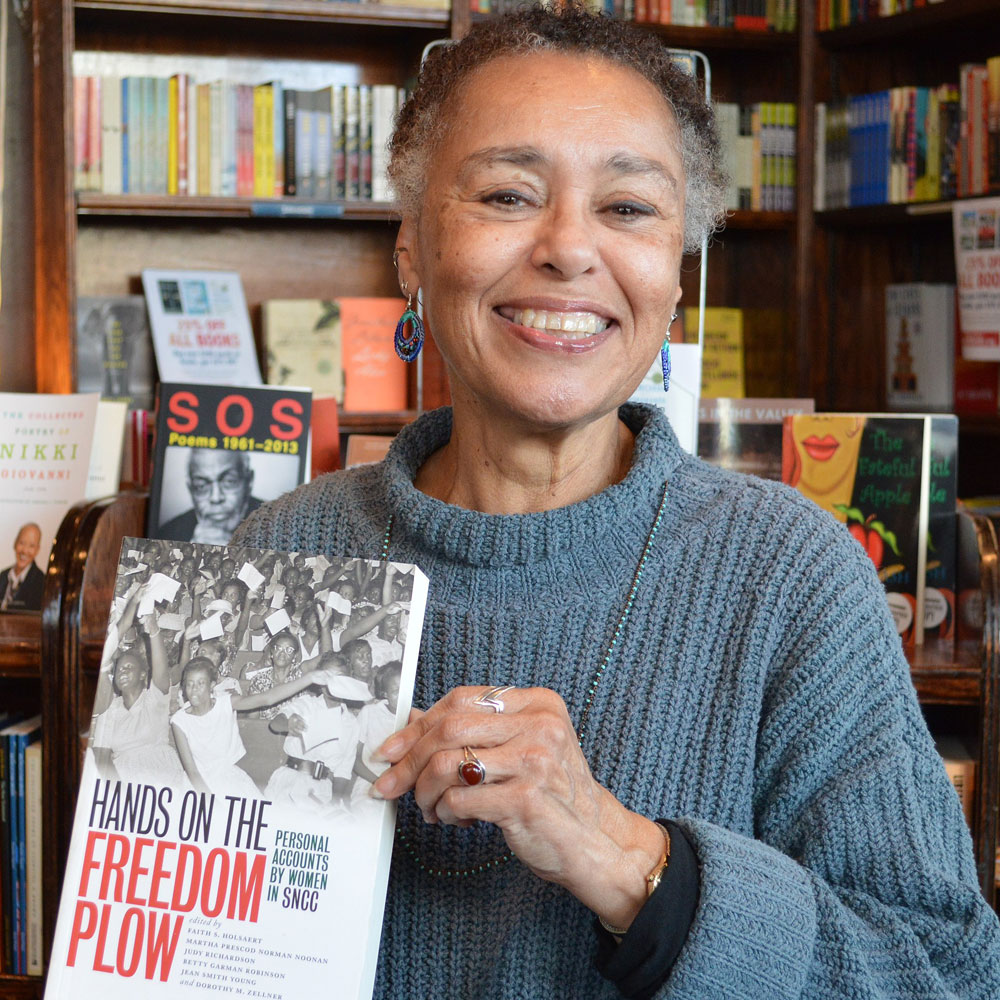

Deborah Menkart, executive director of the Washington, DC-based nonprofit Teaching for Change, which provides materials for teachers ready to follow Chacon’s lead, sees a critical mass gathering that recognizes the need for a new approach.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“There have always been teachers committed to truth-telling,” she notes. “But I think this moment…has also impacted teachers in recognizing that this country must come to grips with the reality of institutionalized racism. It’s not a question of just diversity.”

This change is also reflected in recent polling from the Southern Poverty Law Center, which says “the overwhelming majority of Americans support teaching anti-racism in schools.” According to sociologist James Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, there’s also been “a shift in how teachers are approaching subjects like American history.”

“After George Floyd, after the positions, shall we say, taken on race relations by our president, a lot of teachers realize they’ve got to do better than just teach the textbook,” Loewen observes. “So, I think there’s real opportunity for students and teachers to cooperate in bringing out an exciting new kind of US history courses in our schools.”

Further signs of this momentum can be found in the efforts of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education to develop new materials to support the work of the state’s teachers. In an email to the Globe, Reuben Henriques, the agency’s history and social science content lead, describes new resources meant to help teachers “be more inclusive, critical, and responsive” and “include more support around centering students’ identity, race, and lived experiences” school civics projects.

The Boston Teachers Union has made supporting this effort part of their school board negotiations. In a comprehensive proposal they have put forth, they are asking that “stakeholders be part of the decision-making process for design and implementation” of a new approach that will include piloting a new Ethnic Studies course in the current school year. They are also asking that funds be devoted to the ongoing development of new curricula and teaching materials and to providing several trained staff who can support and implement this new approach.

The union further requests the district develop “community partnerships” to “create place-based opportunities for students to collaborate” and compensate “students for participation in any extracurricular activities or committees” and “community partners for their expertise, time and resources.

Chacon feels hope in this moment. “It feels like it can happen,” she says. “I think [this] is a different conversation than the reckoning. Reckoning is acknowledging the thing exists. For my kids, they know it exists. It’s happening to them.”—Martin Levine