September 13, 2016; The Atlantic

It’s stressful enough being in a war zone, not knowing if the next shot or explosion you hear will be the one to end your life or maim you. When a woman enlists and is sent overseas into combat, she acknowledges being killed or seriously injured as a possibility. But there’s also a sense of pride and patriotism in defending your country along with your fellow countrymen and women. However, getting raped by a fellow soldier or a commanding officer is nothing a female soldier anticipates or signs up for and the barbarity and betrayal leave lifelong scars.

“Some [female soldiers] expect to go to war knowing and embracing the fact that there is a possibility of being killed but never thinking of a possibility of being raped,” says Ginger Miller, founder and CEO of Women Veterans Interactive, a Virginia-based nonprofit that works with female veterans.

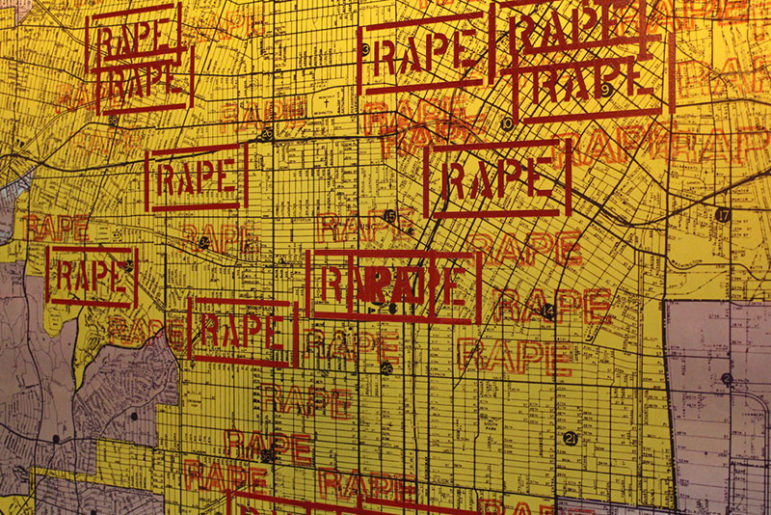

The American Psychological Association reports that reports of sexual assaults in the armed forces went up about 88 percent between 2007 and 2013. There were 2,688 reports in 2007, compared to 5,061 in 2013—and that’s just the tip of the iceberg: The Department of Defense says less than 15 percent of military sexual assault victims report the incidents. If so, that means that there may have been as many as 18,000 military sexual assaults in 2013 out of approximately 203,000 service women.

Another report, this one released by the Pentagon in 2014, revealed an eight percent annual increase in reported sexual assaults. Perhaps even more troubling was the finding that 62 percent of female service victims also reported being targets of retaliation.

Why? As with the civilian sector, reports of rape are low because many in society lay some if not all the blame on the victim. But unlike the civilian sector, where a victim who’s assaulted at work can quit and change jobs, leaving early is not an option for military victims if they want to receive an honorable discharge. It’s no surprise, then, that so many female military victims are subsequently diagnosed with PTSD. The agony and fear of seeing your perpetrator, sometimes on a daily basis, must be tormenting.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On top of that, some servicemen who are convicted of rape merely get a slap on the wrist and continue to serve alongside their victims. Unlike the inconsistent definitions reported throughout the federal government in a recent inspector general’s report, the Uniform Code of Military Justice clearly defines rape. However, it leaves the punishment up to “as a court-martial may direct.” Some military members convicted of rape only receive a drop or two in rank and a fine for such egregious crimes, whereas a Department of Justice analysis of rape and sexual assault in the civilian sector reported that in 1992, a little more than two-thirds of convicted rape defendants received prison sentences with an average term of just under 14 years. Many sentences also included additional penalties like fines, victim restitution, required treatment, community service and other penalties.

It’s small wonder, then, that reports of rape in the military are lower than in the civilian community. Conviction rates in the military are even lower—less than one percent. NPQ reported last April on activists who charged the Pentagon with misleading lawmakers on military sexual assault cases. There was talk on the Hill about removing the authority of senior officers to determine whether or not to prosecute sexual assault cases and instead hand that decision over to seasoned military trial lawyers.

Supporters of improving the military justice system believe doing so would prompt more victims to come forward. Miller says a fairly large number of women veterans opened up about having been raped after meeting or hearing her talk. “The stories are some of the most horrific I have heard because they all have been raped and some by more than one person, and to make matters worse for the women that have the strength to come forward, they are not initially believed.”

Nonetheless, recent congressional attempts to tighten up the Military Justice Improvement Act failed in both houses. Others, like one presidential candidate, have implied that women should not serve in the military at all. “What did these geniuses expect when they put men and women together?“ asked Donald Trump. He attempted to “clarify” his tweet during a recent forum interview with NBC’s Matt Lauer.

Luckily, even in such closed systems, persistent advocates take risks and eventually may see the movement that’s needed to redress even the most protected of problems. Miller feels there should be “funding set aside to create a national outreach program for [military sexual trauma (MST)] survivors” in which veterans who are also MST survivors can provide peer support to fellow victims. Miller, who also served in the military, feels the military must hold its members accountable for such crimes and treated the same, regardless of rank.—Scott Shirai