March 5, 2019; The Atlantic

As Alia Wong writes in the Atlantic, “Two centuries ago, Congress passed a law that kicked into high gear the US government’s campaign to assimilate Native Americans to Western culture.” The Civilization Fund Act of 1819, passed on March 3, 1819, aimed to infuse members of native nations with “good moral character” and vocational skills. It ultimately led to a network of boarding schools.

As a National Museum of the American Indian webpage explains:

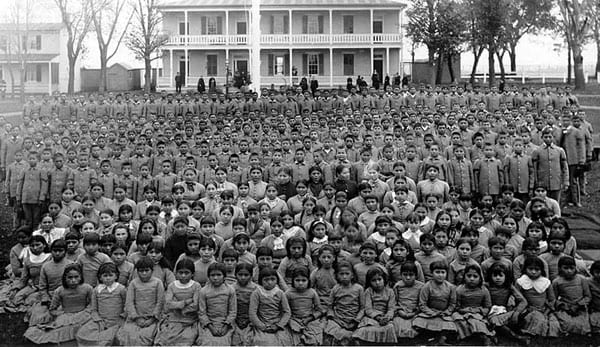

At boarding schools, Indian children were separated from their families and cultural ways for long periods, sometimes four or more years. The children were forced to cut their hair and give up their traditional clothing. They had to give up their meaningful Native names and take English ones. They were not only taught to speak English, but were punished for speaking their own languages. Their own traditional religious practices were forcibly replaced with Christianity. They were taught that their cultures were inferior. Some teachers ridiculed and made fun of the students’ traditions. These lessons humiliated the students and taught them to be ashamed of being American Indian.

As NPQ has noted, it was Colonel Richard Henry Pratt who established what’s arguably the best known of the boarding schools in 1879 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Pratt infamously said his goal was to “Kill the Indian, save the man.” The schools, as Wong explains, were at the heart of the colonial project “to stamp out America’s original cultural identity and replace it with one that Europeans had, not long before, imported to the continent.”

David Treuer is a member of the Ojibwe band of the Chippewa. Treuer grew up at Leech Lake, once home to the late American Indian Movement cofounder Dennis Banks. Treuer, a historian and novelist, has a new book, The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America From 1890 to the Present, which debuted at number 13 on the New York Times’ hardcover nonfiction bestseller list last month. In that book, Treuer explains that “the full effect of the boarding school system wouldn’t be understood until decades after the agenda of ‘civilizing the savage’ ground down.”

“Education,” Treuer explains to Wong, “was something that was done to us, not something that was provided for us.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The boarding schools are a great example of that: They were a means by which the government was trying to destroy tribes by destroying families. This is partly why education is such a tricky thing for Native people today. How are you supposed to go to school and learn about Mount Rushmore yet know that each person promoted the killing of Indian people? How are you supposed to say the Pledge of Allegiance to a country that was trying to kill and dispossess you and caused the horrible suffering of your parents and grandparents?

In the US, mainstream accounts often hide colonizing practices. Last month, NPQ profiled how the Jamestown Settlement, in marking the 400th anniversary year of when the first Black slaves arrived in Virginia, avoids the use of the word “slavery.” In The Guardian, Daniel Immerwahr wrote last month that, “The dispossession of Native Americans and relegation of many to reservations was pretty transparently imperialist,” but schoolchildren who recite the Pledge of Allegiance still say “to the Republic for which it stands”—not empire.

This illusion is maintained in part through exclusion. Treuer tells Wong that, “People tend to read American Indian history as a sideshow to American history; it’s treated, at least in schools today, as a breakout unit that one trots out around Thanksgiving, in November.”

The good news, Treuer says, is that “things are starting to change.” A cultural revival in Native America is evident, one marker of which was the election of the first two Native American women to Congress last fall. Ironically, Treuer contends that boarding schools helped birth the American Indian Movement, much as British universities inadvertently trained independence movement leaders like Mahatma Gandhi.

As Treuer explains, the schools “took all these Native kids from different tribes who previously knew nothing about, or had been habitual enemies with, each other and put them in schools to suffer together. As a result, when they left school and went back to their homelands to promote the welfare of their individual tribes, they were armed with a network of other like-minded, educated people on whom they could rely.”

This is not to deny “the ‘legacy of chronic trauma and unresolved grief across generations’ as a result of colonialism, genocide, forced migration, boarding schools, and relocation” that NPQ’s Ember Urbach has highlighted. Still, Treuer remains hopeful. “I look at my own children, other people’s children…to them, being Native is not merely or only to be of the past, or to suffer, or to be a victim, or to be less than ideal Americans.… Native kids today are way smarter and better off than I was.”—Steve Dubb