This article comes from the spring 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

In looking at any kind of policy—public policy (policy made by public officials), organizational policy, or even personal policy—the relationship between the policy and its target may change. The sociological concepts of cultural lag and structural lag are helpful in understanding this process.

In sociology, cultural lag refers to a situation where norms lag behind technical developments:

The term cultural lag is used to describe the situation in which technological advancements or changes in society occur faster than the changes in the rules and norms of the culture that goes along with those advancements or changes. This can lead to moral and ethical dilemmas for individuals as the new social norms are developed.1

Contrarily, structural lag refers to situations where social structures have moved faster than the norms that govern them.2

And there can be instances of both lags operating at the same time.

Additionally, there may be lack of fit among cultural elements themselves (cultural discordance) as well as lack of fit among structural elements (structural discordance).

Old policies that seemed like (or were) a good idea at the time require reexamination when their practices and impacts, taken collectively, have the opposite effect of that which was (apparently) intended—a good example of cultural lag. In that spirit, this article proposes that we reexamine policies governing tax expenditures (forgiveness of various kinds) for organizations in the nonprofit sector.

5 Reasons for Reconsidering Nonprofit Tax Exemption

First, tax exemption for certain entities has a long history.3 Tax deductions for charitable contributions and tax expenditure (tax forgiveness) have a long history also, nicely detailed in a figure with the title “Major Exempt Organization Legislation, 1984–Present,” in “A History of the Tax-Exempt Sector: An SOI Perspective,” by Paul Arensberger et al.4

An excerpt of the table follows (with two key sections italicized):

Major Exempt Organization Legislation, 1894–Present

Tariff Act of 1894—Earliest statutory reference to tax exemption for certain organizations.

Revenue Act of 1909—Introduced language prohibiting private inurement.

Revenue Act of 1913—Established income tax system with tax exemption for certain organizations.

Revenue Act of 1917—Introduced individual income tax deduction for charitable donations.5

So, tax exemptions for charitable organizations and religious organizations are over one hundred years old. It may be time to rethink the original organizational purposes of such exemptions and the problems they now represent and create.

Second, the general idea is that American society and culture—characterized by associations, as Alexis de Tocqueville famously noted6—was and is brilliant at getting citizens to focus together on, and work voluntarily to, correct problems and concerns of societal interest. The voluntary aspect is important here, because—at least in Tocqueville’s time—those citizens were not being paid. The contemporary social service sector as we know it was, for all practical purposes, nonexistent at the time. So perhaps it seemed natural that such organizations be exempt from collective costs (taxes) in exchange for their collective contributions. But times have changed, along with historical shifts in what is considered a “social good”—and these are reasons for policy reconsideration. Alan Schenk, professor of law at Wayne State University, opines:

State and local exemptions from income tax for qualified organizations, including churches, universities, charitable foundations, etc., generally follow the federal rules. Due to abuses, however, these organizations are subject to UBIT (unrelated business income tax). The states have their own rules on their property, excise, and sales taxes. Some nonprofits voluntarily pay some state and local taxes that they are not obliged to pay.7

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A third reason for reconsideration is that the exemptions have expanded to cover both federal and local tax expenditures. This adds up to a huge dollar amount, considering the size of the assets base under consideration: $3 trillion in 2015.8

Fourth, the tax expenditure not only includes tax abatement but also tax freedom from capital growth. Large institutions (foundations, universities, hospitals, etc.) have endowments, the growth of which is not taxed, either.

Fifth, nonprofits seem to have forgotten that this large fisc is a critical source of support. One could also consider this tax forgiveness a liability, such as a noninterest loan. We have yet to see an annual report that lists the tax expenditures in any way.

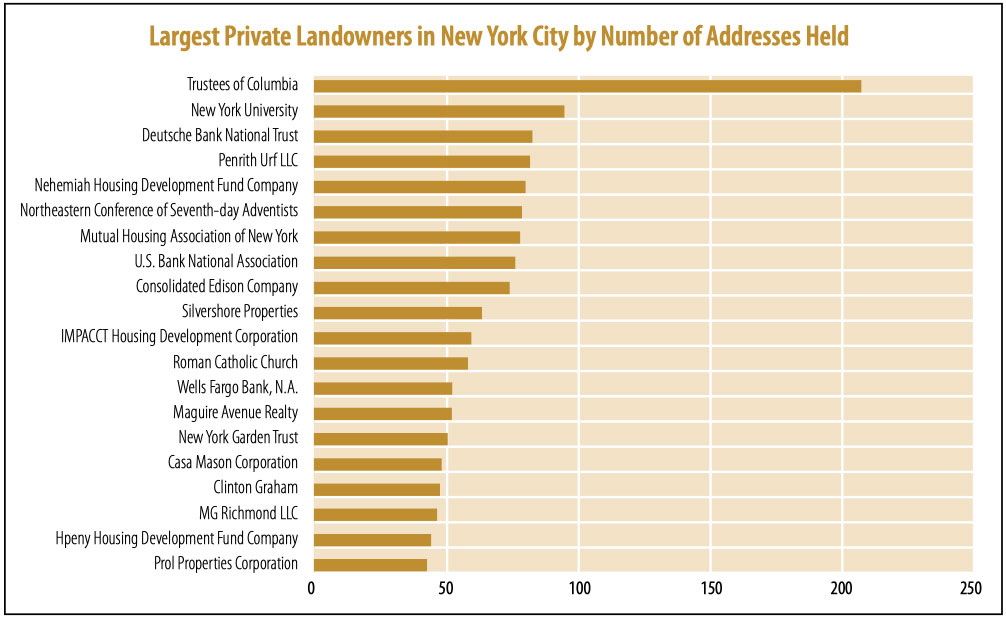

As one considers the very large nonprofits and the impact on their locations, additional questions arise, such as the tax abatement of institutionally owned property. Surely no one would object to a modest tax abatement; but when large nonprofits own vast swaths of real estate, they change the entire character of the tax structure of the area—like a large fire creates its own weather. In New York City, for example, the Catholic Church is probably the biggest landowner, followed closely by two very large and prestigious private universities, according to the Economist.9 The graph below, from a 2016 study, puts the Catholic Church lower than the Economist rating, but two other nonprofits, Columbia University and New York University, are at the top of the list.10

As nonprofits increase their property ownership, this exemption places stress on municipalities, because the tax base drops. Perhaps an appropriate discussion to have would be to consider some limitations on land acquisition, as well as tax-free holdings and growth (for the billionaire nonprofits). Maybe we should have less of a concern about land acquisition per se, and more of a focus on requiring these large landowners to pay a fair and equitable share of the taxes on the land that they own.

One might ask at this point how we have arrived at such a situation. One reason is that, first of all, from a policy perspective, most policies are not reviewed/refurbished unless prompted by a crisis. Second, the large nonprofits—universities, foundations, hospitals, and churches—are not without influence. So, questions about financial privilege and “cash warehousing,” while mentioned, are not gaining traction. Are such great collections of money serving the public good? Or are they simply Scrooge McDucks in academic, medical, or clerical regalia?

Another reason could be that the concept of “social contribution” may vary widely or have undergone an historical shift, which has created a cultural discordance and lack of “goodness of fit.” From the orientation of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to that of the Koch brothers, the ability to sequester funds may allow for the unrestrained pursuit of singular goals, with no appreciable oversight, control, or review.

Exemption Requirements—501(c)(3) Organizations

To be tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, an organization must be organized and operated exclusively for exempt purposes set forth in section 501(c)(3), and none of its earnings may inure to any private shareholder or individual. In addition, it may not be an action organization, i.e., it may not attempt to influence legislation as a substantial part of its activities and it may not participate in any campaign activity for or against political candidates.

Organizations described in section 501(c)(3) are commonly referred to as charitable organizations. Organizations described in section 501(c)(3), other than testing for public safety organizations, are eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions in accordance with Code section 170.

The organization must not be organized or operated for the benefit of private interests, and no part of a section 501(c)(3) organization’s net earnings may inure to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual. If the organization engages in an excess benefit transaction with a person having substantial influence over the organization, an excise tax may be imposed on the person and any organization managers agreeing to the transaction.

Section 501(c)(3) organizations are restricted in how much political and legislative (lobbying) activities they may conduct.

Source: IRS, “Exemption Requirements—501(c)(3) Organizations,” accessed February 17, 2020.

…

The time may be upon us when a thorough review of tax expenditures for the “Fortune 1000” tax-exempt organizations is in order. Further, if the Revenue Acts of 1913 and 1917 were passed in order to foster organizations whose missions were to enhance social justice and provide more opportunity for all, then it may be time to reexamine the societal impact of the Revenue Acts of 1913 and 1917 more generally.

Then again, at the political level, it is perhaps not the best time to do such a refurbishment. U.S. society seems to be in the thrall of a renewed trend of cruelty toward those in need. While having significant charitable tendencies and a willingness to lend a hand, there is also a disturbingly deep vein of negativism in our society toward those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder: Black and Brown people, Indigenous people, Jewish people, non-“white” immigrants, women, and the LGBT community—as well as schoolchildren, senior citizens, differently abled people, and other victims of hate crimes.11 Perhaps the better solution would be to look to the nonprofit community itself to recognize some of these problems and develop some tempering policies of its own.

The authors thank Professor Alan Schenk of the Wayne State School of Law for his helpful comments.

Notes

- Your Dictionary, “Cultural Lag Examples,” accessed February 17, 2020.

- The term’s original development, however, comes from gerontology, and refers more to one aspect of social structure outpacing another. The specific case was the increasing numbers of elders in the population and the lack of meaningful positions and roles for them. And see Encyclopedia.com, “Structural Lag,” accessed February 17, 2020.

- Paul Arnsberger et al., “A History of the Tax-Exempt Sector: An SOI Perspective,” Statistics of Income Bulletin (Winter 2008): 105–135.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 106.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. and trans. Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

- Alan Schenk to author, personal communication, December 30, 2018.

- See Brice McKeever, The Nonprofit Sector in Brief 2018 (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, National Center for Charitable Statistics, December 13, 2018).

- Andre Tartar, “The Economist Digs into the American Catholic Church’s Finances, Finds That Cardinal Dolan Is Manhattan’s Largest Landowner,” Intelligencer, New York, August 19, 2012. (Rankings vary depending upon how one measures: buildings, square footage, etc.)

- Recreated with minor edits from Aleksey Bilogur, “Who are the biggest landowners in New York City?,” May 27, 2016.

- John E. Tropman, Does America Hate the Poor? The Other American Dilemma (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 1998).