For Black people living along the Black Belt in the American South, history entails stories of enslavement and fortitude. Black farmers exemplify that balance most strongly as, for decades, they have resisted injustices related to land ownership, debt, and social mobility.

Patrick Chandler Brown, based in Warren County, North Carolina, is redefining what it means to be a Black farmer. Besides preserving his family’s history, Brown is working to transform the trajectory of historically underserved Black farmers through climate-innovative farming practices.

Black Agrarianism and Self Sufficiency

Patrick Chandler Brown is a fourth-generation Black farmer and, as of last year, the newest owner of the Oakley Grove Plantation. The plantation house, which sits on 2.5 acres of land, is located in Littleton, a small town in Warren County. Oakley Grove is so important to Brown because it is the plantation where his ancestors were once enslaved and where his family’s lineage started.

Brown plans to use Oakley Grove as a way to honor his family history and incorporate agritourism into his existing farming businesses. As defined by the National Agricultural Law Center, agritourism links agricultural production with tourism to entertain with and educate about farming, ranching, or any agricultural business. Agritourism can take the shape of corn mazes, bed and breakfasts, educational farm tours, wedding venues, and more.

As of today, there are roughly 50,000 Black farmers, accounting for just 1.4 percent of farm owners in the US.

The agritourism industry grew from $702 million in 2012 to an estimated annual revenue of $950 million in 2017. However, most of that revenue is not going to Black-owned farms as 98 percent of private US agricultural land is white owned. Over the past century, the number of Black farmers in the farming landscape has severely diminished. As of today, there are roughly 50,000 Black farmers, accounting for just 1.4 percent of farm owners in the US. “Since Emancipation, Black farmers have had to fight for a share of this country’s fertile ground, due to a history of racist policies and land theft,” writes Tom Philpott for Mother Jones.

Brown is one of five Black production farmers in the area. He will be the second Black farmer to have an agritourism business in Warren County, after Seven Springs Farm and Vineyard. The importance of Black-owned agritourism is gaining traction; earlier this year, Airbnb partnered with the New Communities Land Trust to launch a Southwest Georgia Agritourism Trail to share the past, present, and future of Black farming in the region.

Alongside agritourism, Brown is gathering funds to make part of Oakley Grove a nonprofit. He secured buy-ins from clients of his existing farm businesses, Brown Family Farms and Hempfinity, who support his vision and are providing the capital needed to bring it to fruition. In addition, Brown is producing a film in partnership with Patagonia that focuses on the history of Oakley Grove and explains how his family lineage came to be. “My ancestors can now rest peacefully to know that the actual property that they built is now owned by a descendant,” says Brown in the film.

Achieving Food Security

Brown Family Farms is an 11-acre production farm that produces organic produce and operates a robust community-supported agriculture (CSA) program. With the farm, Brown is working to get people out of the mindset that you must have large swaths of land to be a farmer. Food sovereignty has always been a focus for Brown as healthy food access continues to be racialized. “One of out every five Black households is situated in a food desert,” states McKinsey & Company in a 2021 article. Brown believes that teaching young Black children how to grow their own food is the best defense against food deserts and food insecurity.

Fortunately, getting started as a farmer is not as difficult as you might think. There is no minimum acreage to register for a USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) farm ID number. Holders of FSA numbers are eligible for various programs and resources like disaster assistance, tax exemptions, and inclusion in the Agricultural Census. Grow houses, high tunnels, hoop houses, and raised beds are all considered farms under USDA perimeters. “Someone could start a no-till raised bed garden in their backyard and obtain a farm number through the USDA and market that product,” says Patrick. For example, if you have a small collard patch, you can apply for food processing certification and package those collards for sale. Profit from such ventures can go towards scaling up, such as by purchasing more land and farming equipment. Having such crucial information is key to fighting food insecurity.

Hemp—A Climate Smart Crop

Brown has found a way to bring his love of farming and climate justice together through Hempfinity, the second half of Brown’s farming business. Hempfinity produces a niche specialty crop—industrial hemp—to help fight greenhouse emissions. Industrial hemp, or Cannabis Sativa, is a climate-smart plant because of its short production cycle, high carbon sequestration potential, and versatility.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Growing climate-smart crops like hemp also enables farmers to earn carbon credits, helping them pay lower input costs by incentivizing farmers to adopt climate smart practices.

Industrial hemp is also a source of biomass and can remediate contaminated soil. Similar plants like kelp, bamboo, and moringa do the same. “It [industrial hemp] gives us an opportunity to create a niche product for a niche market,” says Brown. The difference between commodity and niche production is that the former requires a farmer to grow a lot of something and get paid based on weight. Niche production allows farmers to determine what is in demand and get paid directly. Growing climate-smart crops like hemp also enables farmers to earn carbon credits, which incentivize farmers to adapt climate smart practices by lowering input costs and receiving compensation for the amount of carbon they are able to sequester. The Growing Climate Solutions Act of 2021 gives the USDA the authority to help ranchers, farmers, and private landowners participate in the carbon credit market.

Tropical deforestation accounts for 20 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, making reforestation and forest preservation a critical strategy for combatting emissions. However, it takes decades for a tree to reach its full carbon sequestration capacity. Shorter-term sequestration in faster growing plants, like industrial hemp, creates a fast carbon sink and is a strategy more farmers are interested in turning to.

Brown is particularly interested in helping Black farmers take part in the emerging carbon credit market. Earlier this year, Brown submitted a USDA Climate Smart Commodities grant proposal for a multi-phased pilot project, ReHemption: The Revitalization of Crops, Community and Climate Smart Practices, which has received congressional support from US Senators Cory Booker and Raphael Warnock. The five-year project aims to provide national leadership for disadvantaged and historically underserved farmers to transition using innovative climate practices. It specifically seeks to establish partnerships with members of the Black legacy farming community. Most importantly, it aims to help underserved producers sustain and thrive in the ever-changing farming industry, promote climate resilient practices, and track carbon sequestration potential from its start.

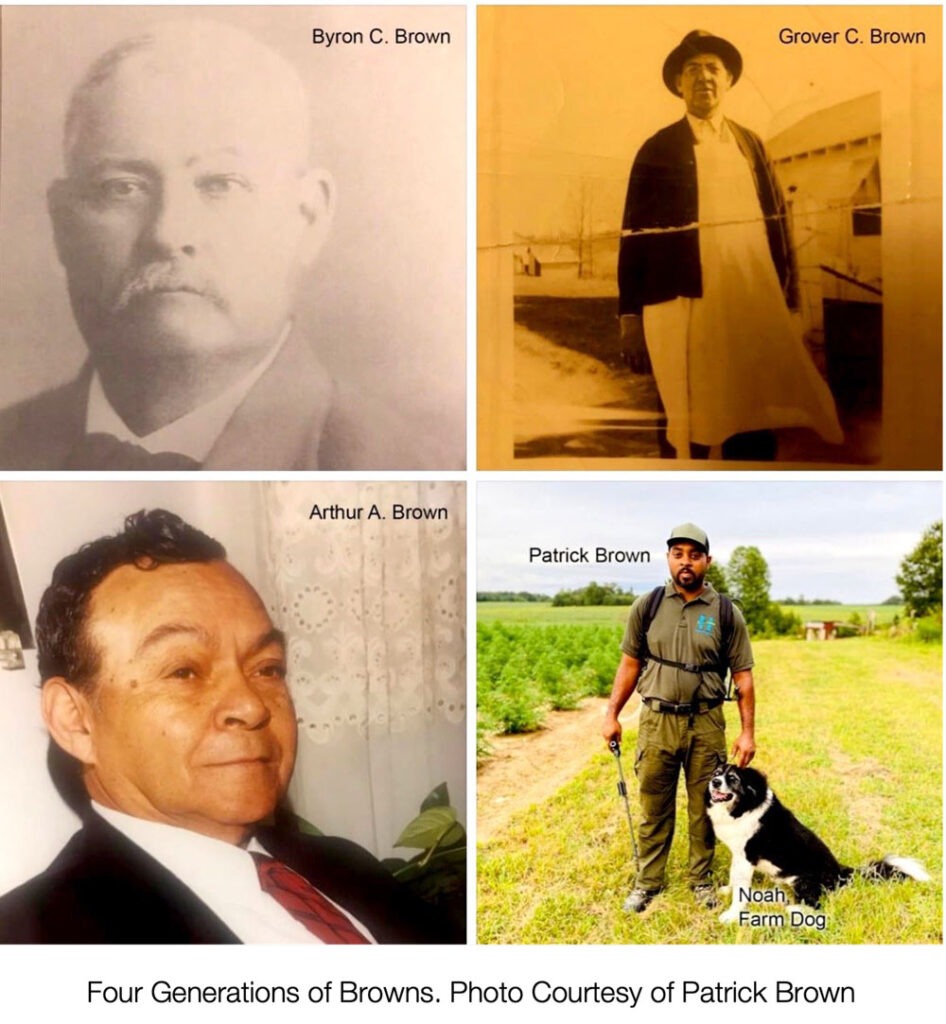

The Brown Family Roots

Brown is the great-grandson of Byron C. Brown, who in 1850s, along with his seven siblings and mother Lucinda Fain, were enslaved on the Oakley Grove Plantation. At its peak, the 7,000-acre plantation had over 170 enslaved persons and was owned by Dr. Lafayette Browne and Mary Ann Falcoun. “The plantation was so big that it was called ‘Browne’s turnout,’” says Brown.

Browne and Falcoun had seven children, amongst them Jacob Falcoun-Browne. He fathered the seven children of Lucinda Fain, a mulatto house slave. One of those seven children was Byron, who lived and worked on the plantation until 1865, when he was about 14 years old.That year, two years after President Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law, set Byron out on a new path.

Byron ran away within a day or two of learning that he was free. He ended up at another plantation southeast of Warren County, where he learned how to farm independently. He eventually moved on to become a sharecropper on the Monticello plantation. When the owner of that plantation passed, he left Byron 200 acres of land in his will. This is the land Brown Family Farms operates today. Thanks to this inheritance, Byron was able to accumulate wealth and willed 250 acres of land to each of his children, including Grover, Patrick’s grandfather. That land was later willed to Patrick’s father, Rev. Dr. Arther A. Brown, who willed it to Patrick Brown.

After college, Brown made Washington D.C. home but would visit North Carolina often. Visits always included a stop at Oakley Grove. On one particular visit, he saw someone in the yard and inquired about who owned the home. He eventually learned that the North Carolina Preservation Authority had been the owner for about five years before selling the property to two retired Duke University surgeons in December of 2020. Patrick finally met the surgeons at Oakley Grove in January of last year. About three weeks later, Patrick got a call from one of them, who asked Patrick if he might be interested in buying Oakley Grove. After some negotiation, they settled on an amount that worked for both parties, and Brown became the owner of the Oakley Grove plantation in May 2021.

Brown is helping Black history define itself as the owner of Oakley Grove. His pilot project is also attempting to shift the narrative and legacy of Black farming to one that is sustainable, resilient, and on a pathway to autonomy and self-determination.