A Chicago-based nonprofit, A Long Walk Home (ALWH), released a report this spring that examines the compounding effects of COVID-19 and systemic racism on Black girls and their families. Entitled Black Girls During the Pandemic and Protest, the report centers the voices and stories of participants of the nonprofit’s Girl/Friends program by providing first-person narratives of the negative impacts COVID-19 has had on multiple spheres of Black girls’ lives in Chicago, including school, home life, work, mental health, and wellness. The report was co-authored by Alliyah Allen, ALWH codirectors Salamishah Tillet and Scheherazade Tillet, Leah Gipson, and Margaret “Mimi” Owusu.

For the report, 29 program participants (Girl/Friends) were surveyed, as well as 13 of their parents. ALWH uses arts programming and wraparound supports to empower young people, with the aim of ending violence against girls and women. Founded in 2003, the group works with artists, students, activists, therapists, community organizations, and cultural institutions to advocate for racial justice and gender equity in schools, communities, and beyond. The period covered in the report centers on the first six months of the pandemic—starting with the March 21, 2020, shutdown order in the city of Chicago through the peak period of racial justice protests in June and July to the decision of Chicago Public Schools to have all-virtual instruction for the fall 2020 semester.

National data make clear the pressure-cooker environment that many Black adolescent girls experience, which impacts their mental health. For example, an article published in the Journal for Community Health in 2019, coauthored by James H. Price, an emeritus professor in the school of public health at the University of Toledo, and Jagdish Khubchandani, a public health professor at New Mexico State, found that suicide death rates for Black American girls ages 13 to 19 increased by 182 percent from 2001 to 2017.

For participants of ALWH’s Girl/Friends program, social isolation due to school closings, quarantining, and sheltering in place contributed to an increase in reports of suicide ideation, with eight of the 29 girls (27 percent) surveyed indicating that they had experienced “increased suicidal ideation or attempts during the COVID-19 quarantine.” The authors add that during the initial stay-at-home order in Illinois, Black girls who participated in Girl/Friends reported “increased nightmares/loss of sleep (62 percent) and increased feelings of anxiety (69 percent), depression (59 percent), and hopelessness (41 percent).” The loss of personal freedoms, disconnection from peer and adult networks, and increases in neighborhood and police violence contributed to feelings of hopelessness and loss of purpose.

In a podcast interview with Melissa Harris Perry, Salamishah Tillet notes that the survey responses prompted a few questions for the team. “How does one respond to loss? How does one respond to isolation? How does one respond to a kind of closing of schools that oftentimes provide some resources, particularly around counseling for the girls that we work with?” In response, the organization made several shifts to its programming.

During the first few weeks of the pandemic, ALWH distributed a total of $30,000 in emergency micro-grants to current Girl/Friends, alumnae, and their families. Recipients could use the grants ($500–$2,000) as they saw fit, with most participants choosing to use funds for medical supplies, housing, and bills. In addition to providing emergency micro-grants, the organization provided healing circles, group and individual therapy, virtual tutoring and study halls, and art supplies to support mental health.

Based on their direct experience working with Black girls, the researchers outline five recommendations for improving the livelihoods of Black girls and their families during the pandemic and beyond.

Recommendation #1: Guarantee Equal Access to Health Care and Counseling

The pandemic laid bare inequities in healthcare and the negative impact they can have on the lives of Black girls and their families. For example, in the US, medical racism has led to unequal access to quality healthcare, inadequate medical facilities, and intentional exclusion of African Americans from the medical field. Medical racism, coupled with structural racism in housing, employment, and food access, produce disproportionate health disparities by race. These factors came to a head during the early stages of the pandemic. Mass layoffs led many Black girls to take on low-paying, essential roles in nursing homes to support their families, placing them at considerable risk of infection. According to the researchers, these factors, taken together, provide more justification for investment in STEM (science, teaching, engineering, and math) programming to develop pathways to careers in the medical field as physicians and nurses.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In addition to investment in career pathways, the authors advocate for equitable access to healthcare, universal health insurance, improved healthcare facilities, and policy that leads to improved health outcomes, food security, and housing.

Recommendation #2: Invest in Black Girls

As was widely reported in 2020, the pandemic has led to a national increase in demand for social services. Likewise, Black-led, youth-serving organizations in Chicago also saw a dramatic increase in the need for support services. As the report details, Black girls are often at the forefront of movements but go underappreciated for their contributions. As high school student Ariana Williams, a participant in the Girl/Friends program, tells the report authors, “Many Black girl leaders are out here protesting and putting their lives on the line for this, but our voices might get drowned out by someone else.”

This same invisibility leaves too many grassroots Black organizations off the radar of grantmakers. To remedy this, the authors encourage investing in Black, women-led grassroots and community-based organizations that specifically support Black girls, have direct connections to Black girls and their families, and possess a keen understanding of the needs within their communities. The authors recommend the Black Girl Freedom Fund, whose founders include Salamishah and Scheherazade Tillet and #MeToo movement founder Tarana Burke, as an example of a fund to support.

Recommendation #3: End Violence Against Black Girls and Young Women

The isolation caused by quarantining and shelter-in-place orders made Black girls more vulnerable to gender-based violence. Among those surveyed by ALWH, 83 percent of Girl/Friends and 69 percent of their parents reported a history of trauma before the pandemic, with sexual and domestic violence ranked as the most common trauma experiences. To dramatically reduce such numbers, the report recommends permanently instituting strategies created during the pandemic (e.g., emergency housing vouchers) and making them accessible to all survivors of gender-based violence post-pandemic. In addition to permanent supports, the authors call on public authorities to support youth-led community responses. For example, even in the absence of public programs, Girl/Friends have created their own networks of support—launching campaigns to search for missing Black girls, securing housing for girls experiencing violence, and creating online mental health wellness groups.

Recommendation #4: Provide Equal Access to Quality Education and Technology

Effective remote learning requires quality technology and internet access. Many who participated in Girl/Friends reported only having access to a phone for remote learning, which made virtual learning difficult. The researchers recommend that school districts and cities provide internet access and computers to every student during school and summer vacation. Along with appropriate technology, opportunities for social-emotional learning, one-on-one learning opportunities with instructors, online library access, and school supplies were listed as supports most needed by participants.

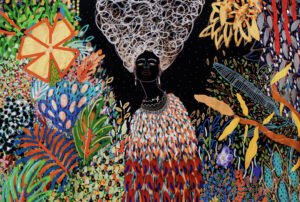

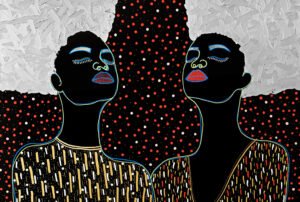

Recommendation #5: Support Creative and Political Vision of Black Girls

The report also recommends funding arts initiatives that develop the creative agency of Black girls. As the authors write, “Whether photography, creative writing, hair, dance, etc., 85 percent of Girl/Friends leaders have engaged in political activity and repurposed art as a mechanism for healing, expression, advocacy, and freedom. Therefore, we recommend direct funding initiatives be created explicitly for these girls. This includes grants, public art projects, and further opportunities to support Black girls as artists.” Art, the report adds, can serve as a critical “vehicle of care.”

Conclusion

While the report is specific to Chicago, the findings and recommendations can serve as a blueprint for action in communities well beyond the Windy City. As the report authors point out, amid the pandemic, many Black girls found themselves “being pushed into adultification and facing challenges including bills, childcare, and maintenance of their households,” leaving many with little time to prioritize themselves and their well-being. It is time to, as the report advocates, make investing in Black girls a leading public policy and philanthropic priority.