July 28, 2014; The Intercept

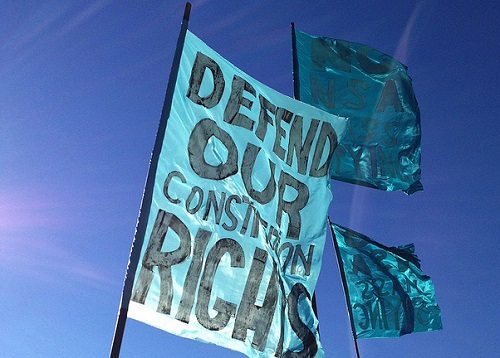

As we all know, our legal rights and our right to an unfettered free press are core to a healthy democracy. But in a joint report entitled “With Liberty to Monitor All,” the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Human Rights Watch warn that these functions are highly threatened by massive domestic spying practices. The report lays out the chilling effects of these practices in some detail using responses to a survey of journalists and lawyers. The report makes the case that the legal and free-press pillars of civil society are rendered less functional by the surveillance practices of the United States Government.

What the reported effects of surveillance are on journalists (from the summary of the report):

Journalists told us that officials are substantially less willing to be in contact with the press, even with regard to unclassified matters or personal opinions, than they were even a few years ago. This can create serious challenges for journalists who cover national security, intelligence and law enforcement, and who often operate in a gray area—working with information that is sensitive but not necessarily classified, and speaking with multiple sources to confirm and piece together the details of a story that may be of tremendous public interest.

In turn, journalists increasingly feel the need to adopt elaborate steps to protect sources and information, and eliminate any digital trail of their investigations—from using high-end encryption, to resorting to burner phones, to abandoning all online communication and trying exclusively to meet sources in person.

Journalists expressed concern that, rather than being treated as essential checks on government and partners in ensuring a healthy democratic debate, they now feel they may be viewed as suspect for doing their jobs. One prominent journalist summed up what many seemed to be feeling as follows: “I don’t want the government to force me to act like a spy. I’m not a spy; I’m a journalist.”

This situation has a direct effect on the public’s ability to obtain important information about government activities, and on the ability of the media to serve as a check on government. Many journalists said it is taking them significantly longer to gather information (when they can get it at all), and they are ultimately able to publish fewer stories for public consumption. As suggested above, these effects stand out most starkly in the case of reporting on the intelligence community, national security, and law enforcement—all areas of legitimate—indeed, extremely important—public concern.

Read the section on Journalists here.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

What the reported effects are on lawyers (from the summary of the report):

Lawyers face a different challenge. They have a professional responsibility to maintain the confidentiality of information related to their clients on pain of administrative discipline. They also rely on the ability to exchange information freely with their clients in order to build trust and develop legal strategy, which is especially important in the realm of criminal defense. Increased government surveillance undercuts these longstanding and central elements of the practice of law, creating uncertainty as to whether lawyers can ever provide true confidentiality while communicating electronically with clients.

Lawyers we interviewed for this report expressed the greatest concern about situations where they have reason to think the US government might take an intelligence interest in a case, whether it relates to the activities of foreign governments or a drug or terrorism prosecution. As with the journalists, lawyers increasingly feel under pressure to adopt strategies to avoid leaving a digital trail that could be monitored; some use burner phones, others seek out technologies they feel may be more secure, and others reported traveling more for in-person meetings. Some described other lawyers expressing reluctance to take on certain cases that might incur surveillance, though by and large the attorneys interviewed for this report seemed determined to do their best to continue representing clients. Like journalists, some felt frustrated, and even offended, that they were in this situation. “I’ll be damned if I have to start acting like a drug dealer in order to protect my client’s confidentiality,” said one.

The result is the erosion of the right to counsel, a pillar of procedural justice under human rights law and the US Constitution.

Read more about the responses from lawyers and their clients here

The report finds that “uncertainty is a significant factor shaping the behavior of both journalists and lawyers. The combination of the sheer number of surveillance programs, the complexity of the underlying legal regimes, and the lack of clarity as to their scale and scope renders it practically impossible for any layperson to discern which forms of communication and data storage are secure and when they may be reasonably subject to surveillance.”

Human Rights Watch and the ACLU strongly urge the United States to:

- end large-scale surveillance practices that are either unnecessary or broader than necessary to protect national security or an equally legitimate goal;

- strengthen the protections provided by targeting and minimization procedures;

- disclose additional information about surveillance programs to the public;

- reduce government secrecy and restrictions on official contact with the media; and

- enhance protections for national-security whistleblowers.

NPQ has written on numerous occasions about the dependence on civil society on civil liberties, but this report sends a chilling shot across the bow for us all.

I would like to acknowledge that the source article for this newswire came from the Intercept, a new news site established this past year by Pierre Omidyar.—Ruth McCambridge