July 28, 2017; New York Times

For the millions of workers who can’t participate in an employment-related retirement plan, saving for retirement just got harder. For the organizations that will face the need to support retirees living in poverty, that work is going to get much harder too.

Thirty thousand participants in the federal myRA program for low- and moderate-income households were informed last week by the Treasury Department of the program’s coming end. This comes just a few months after President Trump and the Republican Congressional majority cancelled an Obama-era policy that made it easier for states to directly provide low-cost IRA programs for employees of small businesses who did not have access to an employer-sponsored plan. Both programs had been created in response to a growing recognition that changes in the economy and the nature of the workplace had left a large portion of the populace without an easy path to saving for retirement.

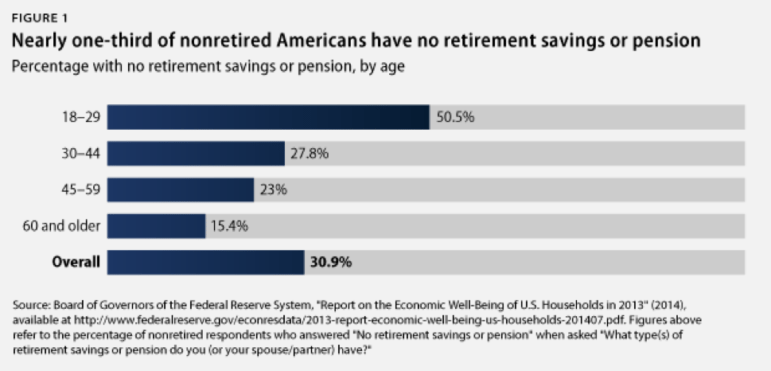

At the request of Politifact, The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College used data gathered by the Federal Reserve System to define the scope of this problem. They found that 41 percent of all 55- to 64-year-olds did not have an IRA or a 401(k) retirement plan. Of that group, 38.5 percent have some other personal saving but “the median amount of their savings is $1,000—in other words, half of them have savings of more than $1,000 and half have less.” Those on retirement will have only the Social Security benefits they have earned, benefits that were never designed to be sufficient as a sole source of support when work ended.

In his 2014 State of the Union address, President Obama recognized this challenge, saying, “Today, most workers don’t have a pension. A Social Security check often isn’t enough on its own. And while the stock market has doubled over the last five years, that doesn’t help folks who don’t have 401(k)s.” He launched the federal myRA program to make saving for retirement easier for those without employers that provided that kind of support.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In a ruling released in August 2016, the Treasury Department went further to address the retirement savings challenge by allowing states to set up plans that enrolled workers in state-sponsored retirement plans. According to Forbes, prior to the Trump administration’s ending federal support, many states had responded favorably, with “over half of the states…considering providing retirement savings programs.”

In cancelling the myRA program the Trump administration emphasized the small number of participants and its high cost as reasons for its decision. U.S. Treasurer Jovita Carranza said in a statement that “Unfortunately, there has been very little demand for the program, and the cost to taxpayers cannot be justified by the assets in the program. Fortunately, ample private-sector solutions exist, which resulted in less appeal for myRA.” The response doesn’t seem to give much thought to the failures in the private sector that caused the problem in the first place.

Opposition to state-sponsored plans seemed to be spearheaded by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. According to CNNMoney, it claimed that “state-sponsored plans would lead to a patchwork of laws across the country. This could make it difficult for small businesses to keep up, especially for those who might have workers who live in a different state.” That confusion was apparently enough to stop states from creating options that these businesses had not previously been willing to provide.

Are these reasons significant enough to end these lifelines toward more secure retirement? In a letter to Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, Senators Patty Murray (D-WA) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) said, “Given that this administration has worked to reduce access to retirement plans for millions of Americans, it is more critical than ever for the Treasury to strengthen one of their remaining options for retirement savings.”

Forbes, reporting on a statement from AARP, noted, “Too many small business employees don’t have a way to save for retirement out of their regular paycheck. That’s 55 million workers.” Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, said, “This is an industry effort to try to preserve that customer base for itself even though they’ve had no interest in that customer base for years. Putting sand in the wheels of these state efforts is a destructive thing to do. The message: You’re on your own for retirement if you don’t have a workplace retirement plan.”

The Obama administration’s efforts served as good beginnings in helping to fill the retirement-savings gap as more and more workers lack access to employment-connected options. Without these programs, many will face their retirement years with limited incomes. Government safety net programs, if they continue to exist, will need to make up for this lack of private savings. Nonprofits whose mission is to help fill those same gaps also have a stake in a solution.—Martin Levine