September 5, 2018; Shelterforce

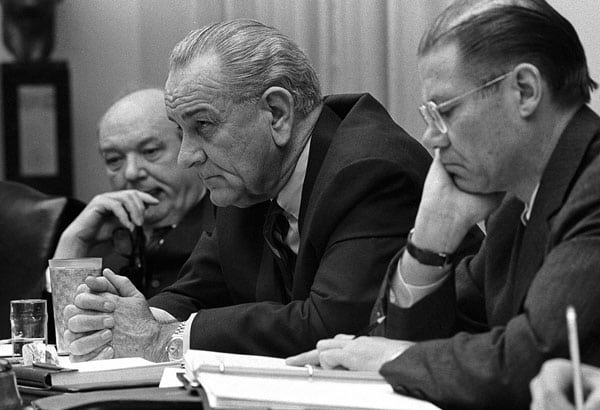

On August 1, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed a bill that he declared “the most farsighted, the most comprehensive, the most massive housing program in all American history,” a bill that promised to ensure “the very precious American right to a roof over your head—a decent home.”

Johnson wasn’t talking about the Fair Housing Act, which had passed three months earlier—one week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. What animated Johnson was the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968. It was known at the time as “the housing act.” Writing in Shelterforce, Fred McGhee contends that this second bill, not the Fair Housing Act, was “the most important housing law passed in 1968.”

“This misremembering,” McGhee adds, “is not accidental—it reflects the race and class trajectory of America over the past five decades…had its promise been fulfilled, many of the problems beleaguering American cities today might have been avoided or at least mitigated.”

The 1968 housing act included a smorgasbord of housing ideas…[including] a robust increase in public housing construction. The act set a national goal of constructing or rehabilitating 26 million housing units, including six million for low- and moderate-income families.

In his signing statement, Johnson noted that, “Over the 10 years of this program, the production rate of federally subsidized housing will be 10 times higher than it has been in the last decade.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The election of Richard Nixon three months later did not immediately end the housing program. McGhee notes that “the HUD secretary who presided over the single largest construction of federally subsidized housing in American history was George Romney, father of former Massachusetts governor and current Senate candidate from Utah Mitt Romney. American housing production between 1968 and 1972 was both robust and diverse.”

But, McGhee observes, “backed by white resistance to integration as well as overall hostility to government housing efforts,” Nixon rolled back the federal commitment later in his term. In its place, McGhee notes, America got “block grants and a new tenant-based voucher program known as Section 8. In other words, deregulation and delegation.” And, of course, further cutbacks occurred over time.

The impact is quite visible in the numbers. For example, a US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) report found that in 1970, the federal government developed 366,100 new units of affordable housing and financed the rehabilitation of an additional 79,700 units—numbers that were more than 10 times higher than the numbers reported for 1961. By comparison, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, according to an Urban Institute report published two months ago, has created or preserved 2.3 million housing units in its first 30 years—an amount that works out to less than 77,000 units a year, barely one-sixth of the 1970 affordable housing production level.

Today, McGhee notes, “even the thought of direct federal provision of affordable housing is nearly unimaginable.” And so, as NPQ has noted, we are left with the inefficient system of tax credits that we have today and even those limited supports regularly face threats of cutbacks.

As McGhee observes, the result of this turn is that millions lack affordable housing today. In his home town of Austin, Texas, McGhee reports that about 10,000 families are on the waiting list for public housing, adding that “The waiting list is perpetually closed, so the actual number [lacking needed housing] is even higher.”

McGhee notes that to rely on the private real estate market on its own to provide safe, decent, and truly affordable housing for low-income families is to expect the impossible. As Emily Badger explained a couple of years ago in the Washington Post, the cost of providing the housing is simply more than people with limited incomes can afford to pay. And that means we have to acknowledge that whether the policy employed involves government subsidies or direct provision, only the public sector can make housing for all a reality.—Steve Dubb