The failure of foundations to put much grant money into rural nonprofits is historic and persistent. Despite frequent promises to the contrary, foundations haven’t done much to narrow the disproportional gap between urban and rural groups’ access to foundation dollars. The toll is increasingly evident in the rural nonprofits across the country that struggle to stay afloat every day.

In Monroe County, Georgia a community health center serving rural communities is closing. As the director of the clinic noted, all too typical of rural areas that lose a crucial service, “Unfortunately, there is not another rural health center or clinic in the county. Most will find that they will have to seek out this type of health care outside of their own county.” The money to stay open simply isn’t there.

In Mississippi, the state is contemplating closing mental health facilities that serve rural areas due to a lack of funding. A patient who had received help for her bipolar disorder echoed the Monroe County sentiment: “closing facilities would leave a lot of people with no place to go.”

In Nelson County, Virginia, the tiny Rural Nelson has been struggling to continue its service of providing community education and information about governmental services. Individual donations have been the key to keeping this civic service alive, but they’re hard to come by.

How are foundations responding to the challenges that rural nonprofits face in dealing with these and other rural issues?

FREE DELIVERY | Click Here to sign up for THE COHEN REPORT, Delivered to your Inbox >>

Foundations have long talked about how much they care about rural America and examples of model rural grants. There are plenty of heartfelt statements about how much foundations care about rural areas, but something is missing year after year—dollars. There are real heroes and heroines in U.S. philanthropy for whom rural America is undoubtedly grateful. They are the champions for the cause within the halls of this overwhelmingly urban sector. Their challenge remains as immense as ever.

Part of that challenge is the difficulty in assessing foundation’s rural grant making. It is difficult to tell with precision how foundations are doing because the definitions of rural are vague, and the classification of foundation grantmaking no clearer. A foundation grant that might be classified as “rural” could well be serving urban areas as well. Nonetheless, there are some indications to suggest that rural philanthropy has hardly shown evidence of making the kinds of major leaps that rural communities need.

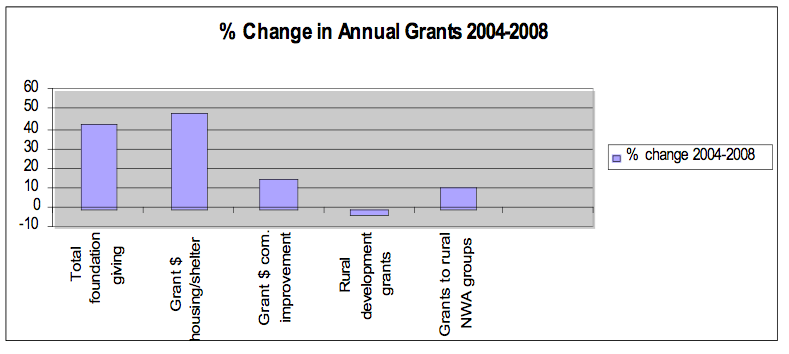

In an analysis of grants categorized as “rural development” (domestic, not international) in the Foundation Center’s online database (containing reportedly the grants of more than 100,000 grantmakers with more than 2.2 million grants) for the years 2004 through 2008, rural development has not fared well in foundation grant portfolios. Between 2004 and 2008, annual foundation grants for rural development declined from $92.7 million in 2004 to $89.5 million in 2008. That is a 3.45 percent decrease in rural development grantmaking during a time total annual foundation grantmaking increased 43.4 percent. (see graphic #1)

Graphic #1

If there are still some grantmakers that have not fully reported their 2008 grants, that 3.45 percent decline may be erased, but not to the point where it will be anywhere in the neighborhood of the level of growth of total foundation grantmaking. Moreover, as noted, it is likely that the grants marked “rural development” are hardly likely to be all rural, making the $89.5 million more than likely a gross overestimation rather than undercount.

The list of the top grantmakers to domestic rural development is not surprising. Even without counting their extensive portfolios of international grants, the Ford Foundation and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation stand out as the largest rural development grantmakers for that five-year period. As graphic #2 shows, there are other noteworthy smaller funders in the list. The Northwest Areas Foundation is a large grantmaker due to some large grants made as part of a now-terminated strategic development strategy that are unlikely to be replicated, at least at their seven- and sometimes eight-figure size, by the current leadership of the foundation.

Graphic #2

| FOUNDATION |

Rural Dev. Grants 04-08 |

| Ford Foundation |

$79,989,178 |

| WK Kellogg Foundation |

$69,630,100 |

| Northwest Area Foundation |

$35,374,899 |

| McKnight Foundation |

$27,860,500 |

| CS Mott Foundation |

$13,397,000 |

| FB Heron Foundation |

$12,537,000 |

| California Endowment |

$11,324,558 |

| Annie E. Casey Foundation |

$10,693,588 |

| Libra Foundation |

$10,639,215 |

| Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation |

$10,595,490 |

| Walton Family Foundation |

$10,457,045 |

| John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation |

$7,805,000 |

| Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation |

$7,312,375 |

| Marguerite Casey Foundation |

$7,176,833 |

| Mary Reynolds Babcock |

$6,896,732 |

| Bush Foundation |

$6,246,651 |

| Duke Endowment |

$5,717,068 |

| Otto Bremer Foundation |

$4,705,100 |

| Packard Foundation |

$4,240,913 |

| Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation |

$3,693,049 |

| William and Flora Hewlett Foundation |

$3,631,000 |

| Surdna Foundation |

$3,477,500 |

| Z. Smith Reynolds |

$3,425,400 |

| Paul G. Allen Foundation |

$3,360,000 |

Several of the others focus on specific geographic regions such as the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation (southeastern U.S.), McKnight (largely Minnesota), and the California Endowment (California). Others have more topical interests, such as the business capital grants of the Libra Foundation and the environmental or conservation grants of the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation. Nonetheless, there are smaller foundations with creative and aggressive rural development grantmaking portfolios such the F.B. Heron Foundation headquartered in New York City, the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, also in New York City, the Walton Family Foundation from Arkansas, and Marguerite Casey in Seattle.

Graphic #3

| FOUNDATION |

Rural Dev. Grants 04-08 |

| Benedum Foundation |

$3,328,200 |

| Annenberg Foundation |

$3,250,000 |

| John S. and James L. Knight Foundation |

$3,053,000 |

| Lannan |

$2,925,250 |

| Meyer Memorial |

$2,638,220 |

| Mellon Foundation |

$2,575,000 |

| Bank of America Foundation |

$2,526,500 |

| Rockefeller Philanthropic Advisors |

$2,523,000 |

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation |

$2,481,678 |

| Richard and Rhoda Goldman Foundation |

$2,442,500 |

| John Merck Foundation |

$2,171,000 |

| Energy Foundation |

$2,155,500 |

| Kresge Foundation |

$2,070,000 |

| Meadows Foundation |

$1,784,000 |

| Joyce Foundation |

$1,750,000 |

| Citi |

$1,610,000 |

| Mississippi Common Fund |

$1,600,000 |

| Blandin Foundation |

$1,593,850 |

| Education Foundation of America |

$1,550,000 |

| Seattle Foundation |

$1,460,649 |

| NY Community Trust |

$1,441,100 |

| Minneapolis Foundation |

$1,385,500 |

| Public Welfare Foundation |

$1,377,850 |

| Iowa WEST |

$1,355,952 |

The next 25 largest rural development grantmakers have an even more geographically targeted strategy – Benedum largely in West Virginia, Meyer Memorial in Ohio, Iowa WEST in Iowa, Rasmuson in Alaska – or a strategy limited to specific topical focuses, particularly environmental (Goldman and Wyss, for example).

Graphic #1 doesn’t just portray the gap between rural development grant increases and total foundation grantmaking increases, but the gap between rural development grantmaking and overall foundation grantmaking for housing/shelter and for community development. Within the housing/shelter and community development categories are a number of very experienced and respected rural community development corporations, some affiliated with the NeighborWorks America network and others with the rural program of the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (Rural LISC). Tracking grants to these organizations (49 for the rural affiliates of NeighborWorks, minus those that had significant urban programs, and 24 affiliated with Rural LISC) for these years provides an unusual targeted analysis of rural development grants.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

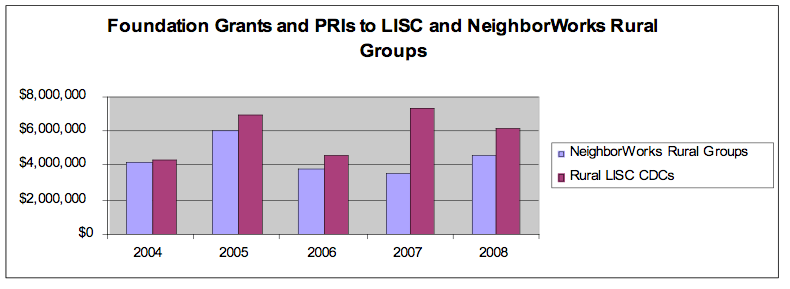

Graphic #4

Graphic #4 shows the annual grantmaking to the NeighborWorks and LISC groups for each of the years in this analysis. In each case the Rural LISC groups are seen doing somewhat better (there is a small overlap between the two lists, and in both, Southern Mutual Help Association in New Iberia, Louisiana was not counted due to its disproportionately large grant totals designated for Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Wilma relief in 2005 and 2006).

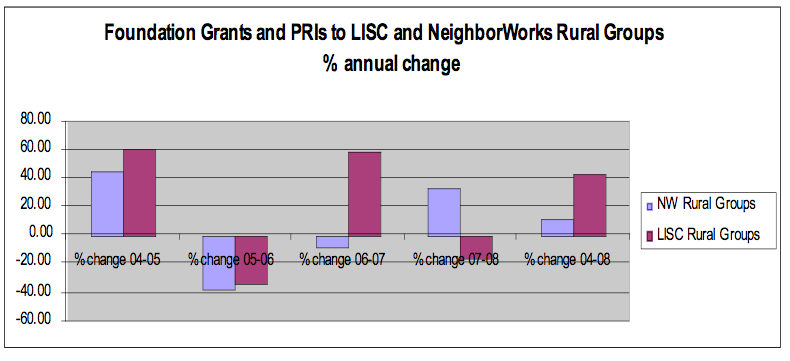

Graphic #5 shows the annual change in grants to the NeighborWorks and LISC groups.

Graphic #5

Overall in this period, comparing 2004 and 2008, annual grants to the NeighborWorks groups increased 11.25 percent and to the Rural LISC groups 42.78 percent, compared to a 48 percent increase in housing/shelter grantmaking – and of course a 3.45 percent decrease in rural development grants. The fact that they outperformed rural development and overall community improvement grant totals for that period may be a testament to the importance of the networks from which these rural CDCs benefit because of their affiliations with NeighborWorks and LISC. Realize however that the 24 Rural LISC groups were those that received foundation grants; an additional 12 are not reflected in these totals because they received no foundation grant dollars.

There are some standout foundation grantmakers supporting the rural NeighborWorks and Rural LISC groups, as demonstrated in Graphic #6:

Graphic #6

Largest Non-Bank Grantmakers to Rural NeighborWorks Groups (grants and PRIs combined)

| FOUNDATION | Grants 2004-2008 |

| FB Heron | $2,980,000 |

| Meyer Memorial | $1,235,000 |

| Cowell | $1,217,000 |

| Northwest Areas | $1,190,000 |

| Ford | $1,150,000 |

| Weinberg | $1,033,332 |

| WK Kellogg | $914,688 |

| MacArthur | $750,000 |

| Marguerite Casey | $675,000 |

| Benedum | $600,000 |

| Dyson | $510,000 |

| Hearst | $425,000 |

| Mary Babcock Reynolds | $405,000 |

| Quantum | $360,000 |

| Amy Tarrant | $350,000 |

F.B. Heron tops the list, though more than half of its output was in the form of Program Related Investments, that is, loans or loan guarantees typically, not grants. Beyond Heron, most of the others are geographically quite limited in their grantmaking – Amy Tarrant, Benedum, Northwest Areas, Cowell, and Meyer Memorial. Interesting, however, is that rural development support of the NeighborWorks groups gets significant support from banks, as shown in Graphic #7.

Graphic #7

Larges Bank Foundation Grantmakers to Rural NeighborWorks Groups 2004-2008

| BANK FOUNDATION |

Grants 2004-2008 |

| Bank of America |

$988,000 |

| JP Morgan Chase |

$513,000 |

| Citi |

$485,000 |

| Wells Fargo |

$440,500 |

| TD Bank |

$229,000 |

| Citizens |

$209,500 |

| Wachovia/Wells Fargo |

$192,000 |

| M&T |

$152,036 |

| US Bancorp |

$138,225 |

| PNC |

$62,500 |

However, the volatility of bank philanthropy due to mergers and acquisitions – and impending losses from burgeoning foreclosures in 2010 and 2011 – suggests that this source of grantmaking might not be counted on as a reliable grant source in the future. Graphic #8 shows the major providers of grants and PRIs to the Rural LISC groups, which largely matches the NeighborWorks list, with Heron at the top, but many of the others are regionally or state focused (Babock, Meyer Memorial, Cowell, Arthur M. Blank, Sandy River, Nina Pulliam Mason, Rasmuson, and Benedum).

Graphic #8

Largest Foundation Grantmakers to Rural LISC Groups 2004-2008

| FOUNDATION | Grants to Rural LISC Groups |

| FB Heron |

$3,905,000 |

| W.K. Kellogg |

$3,364,866 |

| Annie E. Casey |

$2,870,000 |

| Ford Foundation |

$2,745,000 |

| Marguerite Casey |

$1,665,000 |

| Bank of America Foundation |

$1,431,500 |

| Mary Reynolds Babcock |

$1,355,000 |

| Meyer Memorial |

$1,035,000 |

| Cowell |

$1,017,000 |

| Arthur M. Blank |

$699,000 |

| Wells Fargo |

$588,500 |

| Citi |

$525,000 |

| JP Morgan Chase |

$416,000 |

| Sandy River |

$410,000 |

| W.R. Hearst |

$350,000 |

| Surdna |

$304,000 |

| Nina Pulliam Mason |

$300,000 |

| Knight Foundation |

$280,000 |

| Rasmuson |

$264,490 |

| Benedum |

$232,000 |

| Bingham |

$190,000 |

| NY Community Trust |

$185,000 |

| Piper |

$180,000 |

| California Endowment |

$160,393 |

| Rochester Area Foundation |

$157,000 |

| San Francisco Foundation |

$150,000 |

| Wachovia |

$130,000 |

| Wachovia/Wells Fargo |

$105,000 |

| MacArthur |

$100,000 |

In short, after all the philanthropic breast-beating in recent years about how much philanthropy was going to do for rural America, the evidence of follow through still isn’t there. Foundations have yet to show that they are ginning up increased support for rural America.

Don’t blame it on the economy. We specifically chose the years prior to the recession that began largely in the last quarter of 2008; if foundations live up to their cost of determining their payout based on a multi-year rolling average, 2008 grantmaking numbers should not have tanked as precipitously as the economy if at all, given the robustness of the market even in the third quarter of 2008.

What is really happening with philanthropic support – or the insufficient levels of it – for rural America? Elements of several plausible theories probably come into play:

· Where’s Max? Remember when Senator Max Baucus challenged foundations to double their rural grantmaking in a five year period? Led by the Council on Foundations, philanthropy responded with a booklet of self-congratulatory essays about good ideas in rural philanthropy. There are some great things happening in rural philanthropy, some real philanthropic leaders as shown in this list, but glossy publications aren’t the same as real money. Like Waldo, Max has been hard to find on the follow-up with foundations. As the chair of the Senate Finance Committee, he might have learned from his predecessor, Republican Charles Grassley, that foundations don’t respond to one-off Congressional initiatives. It takes a bit more persistence than that.

· Pull yourself up by your bootstraps: The major foundations – and philanthropy as a whole – spliced in an argument for bootstrapping in rural areas. Rather than turning to the foundations that control well above $.5 trillion in tax exempt endowments to put a dollop more toward rural, the Council on Foundations chose to encourage rural areas to look to their local wealth to develop new sources of philanthropy, typically funds as community foundations. This strategy is not only incredibly slow, but there are two other problems: One is that not all rural areas are equally well endowed with wealth to be tapped for philanthropy – the development of new rural philanthropic resources is demonstrably easier and more lucrative in richer rural areas than poorer rural areas. The other is that the “transfer of wealth” between generations that has been touted by some theorists, with trillions upon trillions of dollars leading to some major infusion into philanthropy, has been more than illusory, especially since so much transferable wealth simply evaporated during the recession.

· Metronation strategy: Not surprisingly, most of philanthropy is located in cities – even if the wealth of foundations came from rural areas and rural industries (mineral extraction, agriculture, etc.). Most of the staff of foundations are from urban America and live in cities or suburbs, not ex-urbs or rural areas (except for their second homes). The inexorable urban bias of philanthropy (“where you stand is where you sit”) is underscored by the “metronations” concept of focusing public investment in a number of metropolitan areas that have the highest potential of leverage and growth and assuming that rural areas will benefit somehow by being dragged along. Foundations are hardly immune from this thinking and are as comfortable with this investment focus as the public policy makers in Washington have been.

SUBSCRIBE | Click Here to subscribe to THE NONPROFIT QUARTERLY for just $49

Perhaps the issue is rural advocacy. Foundations have often complained – shortsightedly, to say the least – about a lack of capacity among rural nonprofits. That has always been an incredibly unpersuasive ex post facto justification of inadequate rural grantmaking. Just take a look at the truly impressive array of rural nonprofits in the NeighborWorks and Rural LISC lists to see groups that can match up well against the most sophisticated of their urban counterparts, groups like Coastal Enterprises (Maine), Southern Mutual Help Association (Louisiana), Enterprise Corporation of the Delta (Mississippi), Cabrillo Economic Development (California), Centro Campesino (Florida), Quitman County Development Organization (Mississippi), Chicanos por la Causa (Arizona), and so many more.

But perhaps these stellar rural groups and others aren’t taking on the issue of advocating for more philanthropic grantmaking. Maybe they are saying thank-you to foundations for their grants and not saying to philanthropy as a whole that the foundations should do more, a lot more, for rural America. We wouldn’t be surprised. Advocating to get foundations to do the right thing is something that just about no one does any more. Rural philanthropy is unlikely to make the leaps it should unless rural nonprofits –perhaps aided by the likes of Heron, Noyes, Rasmuson, Babcock, and a few others – say to their peers that glossy publications about nice examples in rural philanthropy don’t do the trick.