January 8, 2014; Pacific Standard

Want to save the world? Just go shopping. If you walk down the aisle of your local grocery store or mall, you will likely see many different products linked to charity. If, by some strange chance, you did not put something “charitable” in your cart, do not worry. You will also be asked to donate at the register.

Cause marketing campaigns and social businesses such as TOMS Shoes, Ethos Water and Nika Water have proliferated in recent years. There is, of course, a lot of good that has come out of such endeavors. Awareness of diseases such as breast cancer and heart disease has increased dramatically, in part due to corporate sponsored advertising campaigns.

But how effective is cause marketing as a form of philanthropy?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

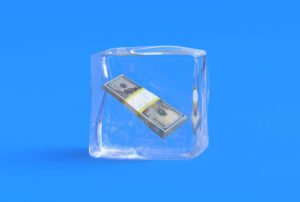

Such advertising leads many consumers to believe the “charitable choice” they need to make is which brand to buy. It is tempting to believe that choosing one brand over another is making a difference. After all, donating some money to some charity is better than not donating at all, right? It depends. As Casey Cep, a columnist for the Pacific Standard, writes, “The market has seduced us into believing that buying goods is doing good.”

This is a mistake. The charitable choice is: in what type of world do we want to live? If we want to live in a world where all children have access to shoes, we must recognize that giving away shoes will not get us closer to that goal. Instead, we must understand systemic causes to poverty and we must commit philanthropic dollars to long-term solutions.

It is, of course, easier to go shopping.

Angela Eikenberry has also written about what she calls the hidden costs of cause marketing. While there are some benefits to cause marketing, Eikenberry encourages us to consider the long-term challenges, including the fact that the market itself creates and propagates many of the social, physical, and environmental problems philanthropy seeks to correct.

It seems corporate philanthropy may compound the market’s pre-existing externalities. TOMS Shoes, for example, has fallen under criticism for the displacing local shoemakers in the countries where it distributes free shoes. Critics have also suggested that Starbucks is unduly profiting off the philanthropy-driven markup on its Ethos Water brand. One rather incensed critic donated $100 to Charity: Water in lieu, he calculated, of purchasing 2,000 non-recycled, landfill-headed plastic Ethos Water bottles.

Cause marketing isn’t all bad, but as Cep reminds us, “Ethics don’t often scale well, so why outsource your charitable giving to a corporation?” Instead, she offers a New Year’s resolution that is simple but profound: Buy less; donate more dollars.—Jennifer Amanda Jones