Throughout the overlapping worlds of science and medicine, thin, White, young, heteronormative bodies are seen as the standard, and are most often represented within medical textbooks. As a result, these bodies are normalized at the expense of others.

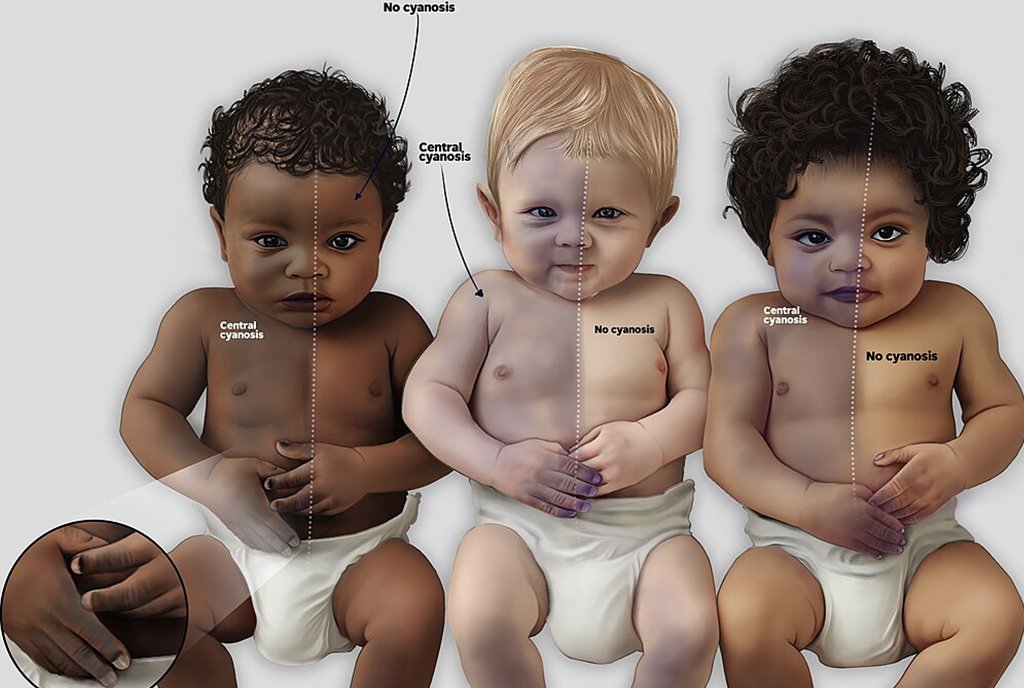

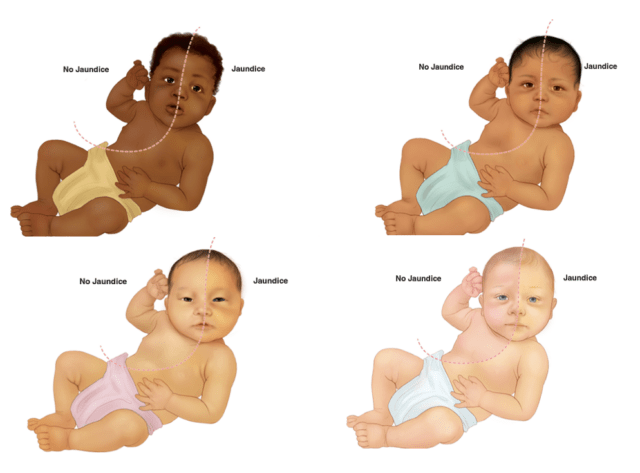

For aspiring care providers who use medical textbooks, illustrations essentially provide the first visual guide for diagnosing and treating medical conditions. Problematically, these bodies, which do not represent all of humanity, become the only frame of reference for disease among all people.

These illustrations’ crucial role in medical training, coupled with their homogeneity, raises the following questions: How does the lack of diversity and inclusivity in medical illustrations perpetuate health inequities? And what are creatives and medical professionals doing to make medical illustrations better reflect the entire spectrum of humanity?

The Lack of Diversity in Medical Illustrations

Research has cataloged the lack of diversity in medical illustrations. A study in the Journal of the National Medical Association that examined “the landscape of published imaging in modern medicine,” which included medical course PowerPoint slides, pre-clinical lecture materials, case studies, and medical textbooks, found stark differences in representation of White people and non-Whites. According to the study’s findings, only 18 percent of images depicted people with non-White skin. The study’s researchers concluded that “there is an underlying racial bias in published images from medical literature with an underrepresentation of minorities compared to the general population.”

How does the lack of diversity and inclusivity in medical illustrations perpetuate health inequities? And what are creatives and medical professionals doing to make medical illustrations better reflect the entire spectrum of humanity?

And even when people of color are shown, the illustrations tend to be of people with lighter skin tones.

According to the article “Representations of Race and Skin Tone in Medical Textbook Imagery,” which presents findings from the analysis of 4,146 images from four widely used anatomy textbooks, the textbooks “overrepresent light skin tone and underrepresent dark skin tone.” Since discrimination against people with darker skin tones is rife throughout the healthcare system, health equity advocates should consider the extent to which “[t]hese omissions may provide one route through which bias enters medical treatment.”

Research on misdiagnoses in underrepresented populations demonstrates the potential real-world consequences of homogenous medical illustrations. Though the heterogeneity of medical illustrations likely has a larger impact, skin cancer misdiagnoses (and other conditions highly reliant on visual diagnoses) most clearly and directly reflect the costs of medical illustration bias. Despite people of color being less likely to get skin cancer, research shows that they are more likely to die from the disease because of misdiagnoses. Malignant melanoma, for instance, is grievously underdiagnosed among patients with darker skin tones.

Thin body types are overrepresented in medical illustrations, and because this overrepresentation can occur simultaneously with the lack of diversity in skin tones, the two forms of inequity can exacerbate each other.

Take, for instance, the experience of a patient shared in the Diverse Health Hub article, “Medical Illustrations Working Toward Health Equity,” who was misdiagnosed largely because medical professionals didn’t understand how cancer manifests in larger, non-White bodies: “They kept giving me misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis, and especially with being a plus-sized Mexican American, they were just like, ‘Oh, if you lose a couple of pounds, you’ll be fine.’ In Sasha’s case, her correct diagnosis ended up as a blood cancer, acute myeloid leukemia—an acute leukemia that progresses rapidly.” When a diagnosis like this remains unidentified and, therefore, untreated, the results can be deadly.

Stories like these, along with staggering statistics on the lack of diversity and inclusion in medical illustrations, demonstrate the need for change. Some individuals and organizations have made considerable gains in this area in the United States and beyond.

Drawing in the Margins: Creating More Diverse Medical Illustrations

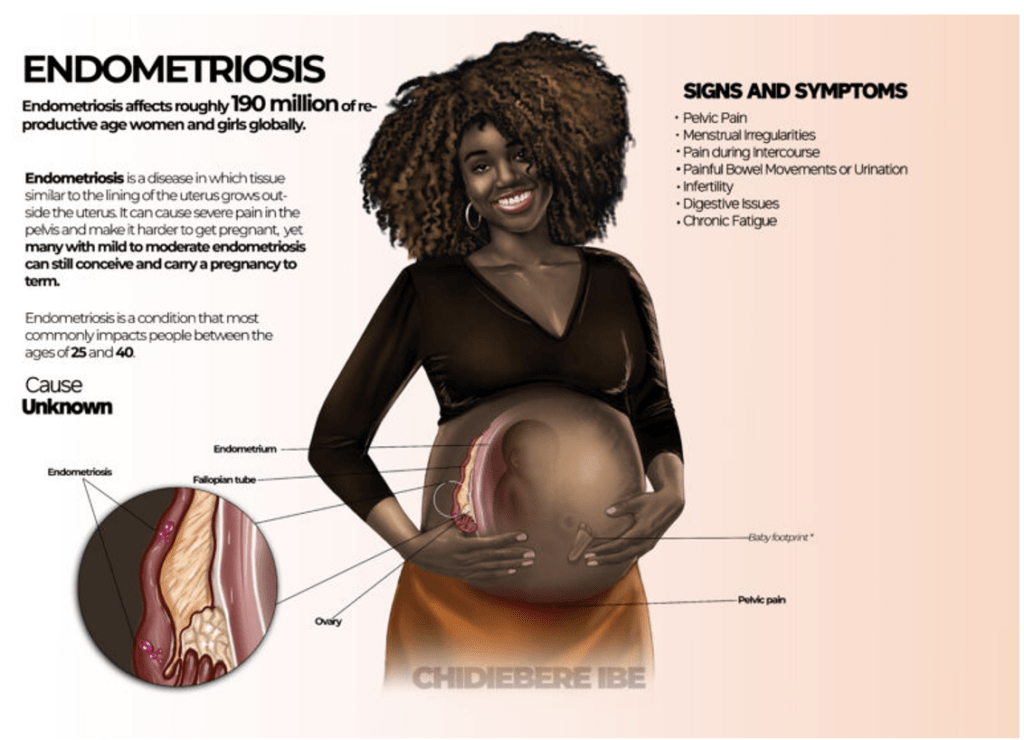

In 2021, Chidiebere Ibe’s illustration of a Black fetus went viral. According to an article about him in Rheumatology Advisor, Ibe decided to begin creating medical illustrations “after searching the internet for reference images and finding that the vast majority of illustrations did not represent people of color.”

“This is a call to everybody that we have a role in addressing the injustice in the healthcare system through proper representation.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Ibe’s work, which garnered much attention online, was able to do so because it was so rare for Black people at the time to see themselves depicted in medical illustrations. Joel Bervell, who featured Ibe on an episode of The Commonwealth Fund’s The Dose podcast, said that a TikTok on Ibe’s work as an illustrator “received over 5 million views in 24 hours, sparking conversation and showing the importance of his work.

Among other roles, Ibe went on to be creative director and chief medical illustrator for the Journal of Global Neurosurgery and medical illustrator for the International Center for Genetic Diseases at Harvard Medical School. According to the Rheumatology Advisor article, Ibe hopes that “the medical system will become more inclusive, with illustrators like himself at the forefront of creating global change and improving overall health outcomes for people of color.”

Ibe has also been instrumental in Illustrate Change, “a movement of inspired artists, healthcare providers, and organizations that can make a difference in the way we think about and approach medical education, as well as healthcare as a whole.” The organization, which is the result of a partnership between Johnson & Johnson, Deloitte, and the Association of Medical Illustrators, aims “to influence medical teaching tools and engage with medical educators to increase diverse representations in medical education and care delivery.”

Ibe, who serves as Illustrate Change’s chief medical illustrator, said about the initiative’s purpose: “This is a call to everybody that we have a role in addressing the injustice in the healthcare system through proper representation.”

Illustrate Change is not only answering the call by creating images that reflect different races and ethnicities but also by creating images for conditions that disproportionately affect people of color, like psoriasis and cataracts. Ultimately, the online repository of images and other resources “aims to be the world’s largest online library of medical illustrations featuring Black, Indigenous and other people of color.”

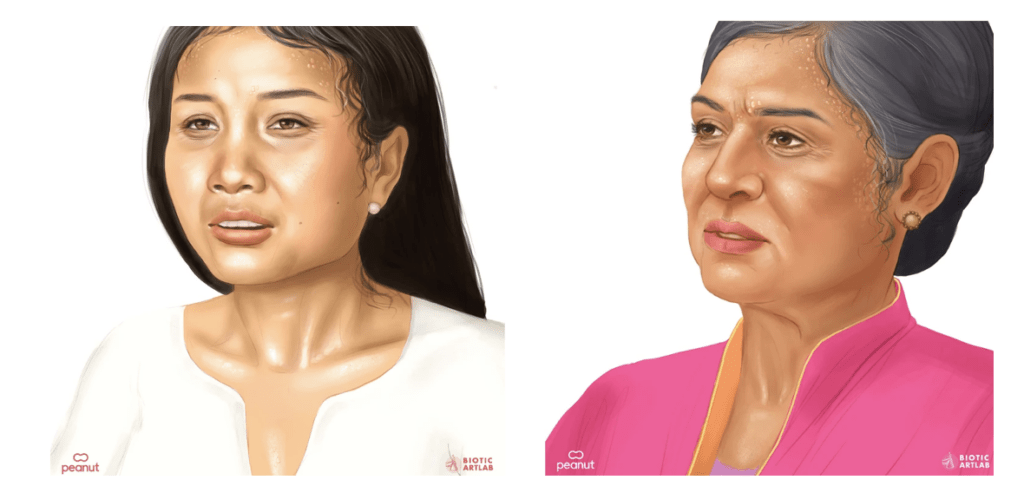

The Reframing Revolution, which according to Forbes is “a royalty-free digital gallery of images that reflect broad diversity of women and women’s bodies,” was also created to help fill equity gaps in medical illustrations. The image gallery includes images of women with different body shapes, skin tones, and age groups including older adults who are too rarely included in medical images, despite the fact that many conditions disproportionately affect older women.

“We’re hoping to not only educate patients and the medical field but society at large. Women and mothers in all their forms, sizes, and identities need to be represented.”

Reframing Revolution’s repository of images also includes illustrations that depict nonbinary and trans people. These types of images of women—images that go beyond gender norms and idealized versions of women’s bodies—can help medical professionals provide better care for women. According to Forbes, “Women [in medical illustrations] have been portrayed as nearly universally white, slim, hairless, young, and able-bodied….When women don’t fit within this narrow set of images, they risk not getting the healthcare they need.”

As Michelle Kennedy, founder and CEO of Peanut, the organization behind the Reframing Revolution, told Forbes, the images are about more than medical education. She commented, “I hope every woman discovers these images at some point in her life, that she feels seen and represented, and that eventually these archaic images we are all so accepting of become a thing of the past….We’re hoping to not only educate patients and the medical field but society at large. Women and mothers in all their forms, sizes, and identities need to be represented.”

Though there is much ground to cover, there is a groundswell of activity, interest, and excitement around creating more realistic, more heterogeneous, and more human images for medical instruction.

Despite threats to diversity, equity and inclusion within medicine looming and the retrenchment of fundamental rights, many advocates remain committed to capitalizing on opportunities to create positive change. Changing the images we use as resources is one integral yet often overlooked area where advocates have made progress in promoting health equity and justice.