October 6, 2015; Washington Post

NPQ has written quite a bit over the last five or six years about the transgressions of for-profit colleges that promised much and delivered little in terms of graduation rates to their often low-income students, leaving them with impossible debt and employment prospects insufficient to pay it off. Couple this with bounty-paid, hard sell recruiters and you have an ethical nightmare that can deeply affect the lives of those least able to afford such a hit.

Since 1992, new regulations that sought to make these schools more accountable for fulfilling their commitments have been promulgated at the federal level, and the reputation of for-profit colleges has taken a beating. All of a sudden, a number of formerly for-profit institutions got the nonprofit bug. Now, in a beautifully written and well-researched report for the Century Foundation, aptly named The Covert For-Profit: How College Owners Escape Oversight through a Regulatory Blind Spot, Robert Shireman not only exposes the “conversions” of four colleges—Herzing University, Remington Colleges, Everglades College, and the Center for Excellence in Higher Education (CEHE)—from for-profit to nonprofit as frauds, but he also discusses beautifully the differences between the sectors in terms that are unusually clear. This is elemental to his thesis, that the inauthenticity of these conversions puts students at continuing risk of falling victim to profiteering by the very same folk who owned the for-profits those institutions evolved from.

Don’t hold your breath for regulation from either the IRS or the Department of Education, writes Shireman, himself a former Department of Education official and reportedly the chief architect of Obama’s crackdown on for-profit colleges. The IRS rarely audits nonprofits for violations of the nonprofit purpose as reflected in things like governing practices, and as long as the IRS is good with it, he writes, so will the DOE be.

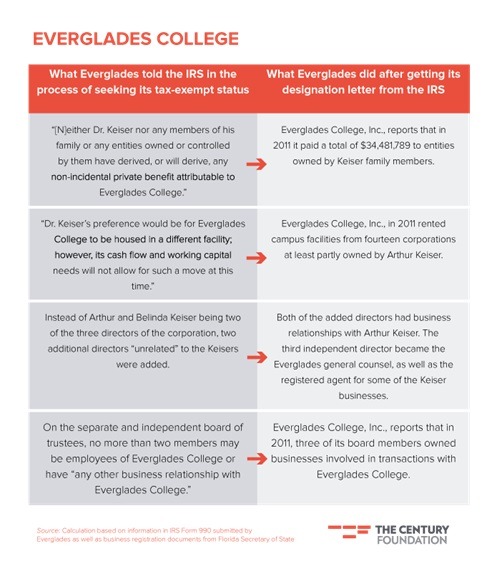

In looking at each of these institutions, Shireman carefully documents spoken commitments against reality, as in the case of Everglades College below. NPQ’s Rick Cohen wrote about Kaiser University’s conversion to Everglades in 2011, looking at the school’s practical reasons for the conversion, but the resulting institution, as we discussed this year, has almost no claim to the nonprofit label.

Shireman’s research shows the veneer of nonprofitness in these institutions to be thin to the point of complete transparency with obvious conflicts of interest everywhere:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But Shireman, as mentioned earlier, does a particularly poignant job in describing the differences between the nonprofit versus the for-profit intention as evidenced through practice:

The unpaid trustees are seen as such a bulwark against abuse that the organizations are, in some cases, allowed to engage in practices that would be illegal in a for-profit context. Many nonprofits, for example, involve vast numbers of people who work for free as volunteers, a practice that is highly restricted in the for-profit environment. Imagine a supermarket or snack food chain enlisting two million underage girls to sell cookies: the operation would be shut down and the companies would be prosecuted. Yet the nonprofit Girl Scouts do exactly that every year, selling 175 million overpriced cookies baked by for-profit contractor bakeries. This “child labor” is not illegal because the Girl Scouts councils are nonprofit: their unpaid boards are trusted to engage in this cookie selling, which they believe benefits the girls and is consistent with the values of the organization. Compared to the supermarket owner or cookie baker, the Girl Scout councils are far more likely to make decisions that truly benefit the girls—because council members do not have a personal financial interest. They are not allowed to keep the money for themselves.

The nonprofit organization that runs Wikipedia offers a different type of example of how being a nonprofit affects the decisions that are made. While Facebook, Google, and other investor-owned Internet companies have all decided to take and sell our personal data for profit, Wikipedia has, remarkably, respected users’ anonymity. Wall Street types, salivating over Wikipedia’s billions of page views and massive troves of salable user data, think the people who run the organization are completely nuts. One analyst detailed all of the ways that Wikipedia could earn money, from selling advertisements to t-shirts, and calculated the website’s lost revenue at $2.8 billion a year—forty-six times the organization’s current income.

Shireman writes that if Wikipedia were a for-profit, “the temptation to grab nearly $3 billion would be impossible to resist, even though it would destroy Wikipedia as we know it. Instead, Wikipedia has kept consumers’ interests at the forefront because it is a nonprofit organization. It is a different beast as a result of being structured without owner-investors.”

Everglades College pretty clearly still has owner-investors, a fact which originally gave the IRS pause in terms of approving its tax-exempt status, but now that it has it, as Shireman says, the system is likely to move slowly if at all to revoke it.

But, he writes, the public is harmed in a number of ways by this subterfuge—students are shortchanged, taxes are lost, and the regulatory environment for education is less than effective.

Most of the recommendations Shireman advances are aimed at the secretary of education who he thinks should immediately:

- Aggressively review recent nonprofit conversions to determine regulatory compliance

- Place a moratorium on Department of Education approval of any additional institutions seeking to be treated as nonprofit

- Revise the documentation and assertions required of institutions claiming nonprofit status

- Seek the assistance of states and accreditors to identify any institutions that are claiming to be nonprofit but may be operating in a manner that inappropriately benefits an individual or shareholder

—Ruth McCambridge