This article is from the Nonprofit Quarterly’s Winter 2016 edition, “Social Media: The New Nonprofit Nonelective.”

If you are one of those nonprofits still approaching social media as simply another tool in your belt, you are very much missing the point.

Social media has been an assumption buster for nonprofits of all kinds, and on a larger basis, for civil society. Its naturally reciprocal and boundary-crossing character is at the very center of its transformative potential—but in some nonprofits this central characteristic may find an open and hospitable host, and in others it may find an unimaginative, slow-to-adjust, recalcitrant setting.

What Makes the Difference?

Much of what has been written about social media and nonprofits is focused on movements and networked ways of working, and this article will draw from that literature, as will those that follow in this edition. However, the principles of practice and the dynamics of social media well used are relevant to most, if not all, nonprofits with constituencies and stakeholders—in other words, with publics who care about what they do.

But that very DNA of reciprocity demands a different set of behaviors from us in the long run. No longer can we just blast out a message and expect it to have impact as is—emerging substantively unchanged from the scrum of interactions among those who receive it, pass it along, argue back with it in sometimes very public ways, or support or shame you for it.

The messages about you do not even need to come from you to mobilize the publics that are already, or potentially, yours. Those messages might come from friends, admirers, and detractors, who may send a sally out in networks where you are known—to have them resonate or not, and go further or not. What is said about you is less controllable but more visible (perhaps) and able to be more broadly influential—even over you—because it acts as a potentially rich feedback loop.

So the loci and initiators of control change, boundaries shift and become more permeable, and digital communication (and remember, that is iterative and relational) becomes a core strategic skill. This is now where we all live.

And when you really embrace all of this, you will find that social media has erased boundaries between formerly separate stakeholders, and thus enforces an integrity of message. The strategic work of the organization then becomes the development and playing out of your identity vis-à-vis the world, your mission, and your stakeholders—and, in some ways, that simplifies the work we do.

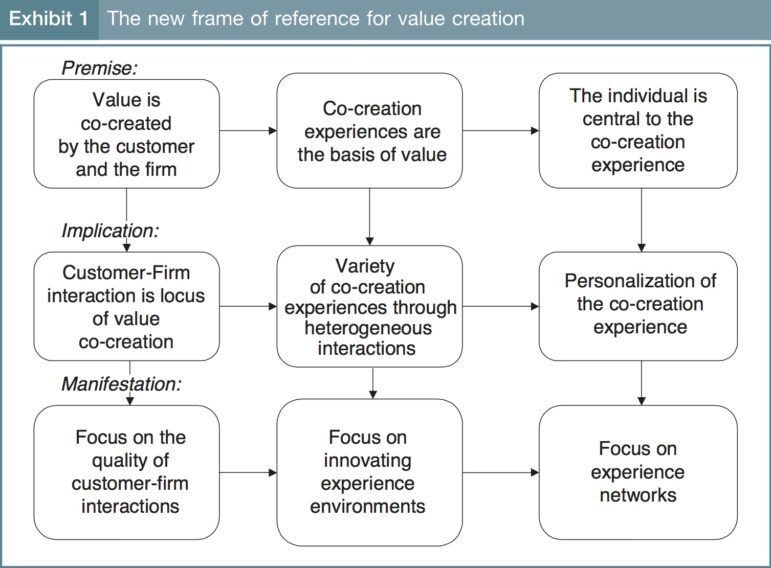

The easy reciprocity also allows for more ease in cocreation of things over time—for instance, of action networks, of ideas about the future we desire, or of campaigns for social change. This creates, according to C. K. Prahalad and Venkat Ramaswamy, connected, informed, and active participants whose engagement enriches the organization and the larger movement.1 (See chart, below.)2

But to get this fulsome response, write Prahalad and Ramaswamy, the organization has to attend to the quality of the cocreation experiences.3 No longer are most movements or initiatives branded to just one organization with one center of command. And, as described by W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg in “Communication in Movements”:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Many NGOs have relaxed their interests in controlling or branding issue campaigns, and offer many avenues for publics to engage directly with each other, and with other issues and organizations in cause networks…. [M]any established cause movements (e.g., feminist, minorities, peace, environment) have also become hybridized, moving fluidly across national borders, targets and issue boundaries.”4

Now ideas can start anywhere and catch on and progress one way in one network and another way in a second—eventually, and sometimes very quickly, finding their way forward to impact through loose ties. This can, at its best, create a commonality of purpose experienced from a diversity of outlets using different approaches, and that can be very impressive to the onlooker. But it also blurs the distinctions between communicator and audience, and for those who want to claim ownership of an initiative, it can seem a problem. Many organizations, however, have adjusted to this new reality.

[F]ar from inaugurating a situation of absolute “leaderlessness,” social media have in fact facilitated the rise of complex and “liquid” [Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press] or “soft” forms of leadership which exploit the interactive and participatory character of the new communication technologies.5

Of course, none of this happens without the facilitating hand of trusted leaders, but where those leaders are, and who they are, is much changed. Positional (vertical) leadership holds less sway, and positions of trust/ credibility (curation inclusive of frames for understanding and action) or the ability to connect and attract between networks (bridging) hold more. Either organizations or individuals can play these roles. But leadership is more a matter of election than of imposition, with bridging and curation functioning more horizontally than vertically—and, in effect, the nature of the leadership is in the skills of being of use to, rather than directing, those around you. If followers lose faith in these leaders’ abilities to discern what it is that particular communities need, others may be right behind them to fill the gap. The roles of bridging and curating are less gatekeeping roles and more informed connecting of people to information and networks, and of networks to networks. As Sandra González-Bailón and Ning Wang wrote in “Networked discontent”:

Online networks of communication…have flattened and decentralized the flow of information; as a consequence, they have helped undermine the old asymmetries that gave prominence to an elite of gatekeepers.6

The habits of gatekeeping are evidently very hard to break for some social engineers—the invitation-only realms where the real decisions are made (complete with sandwiches and technologically up-to-date whiteboards) are increasingly retro and even resented and rebelled against. The fact that some of the money that funds such stuff comes from those who have had a major part in developing social networking—well, that is just a special irony we all have to live with.

In “Peer Production: A Form of Collective Intelligence,” Yochai Benkler, Aaron Shaw, and Benjamin Mako Hill refer to three research concerns for understanding collective intelligence: “(1) explaining the organization and governance of decentralized projects, (2) understanding the motivation of contributors in the absence of financial incentives or coercive obligations, and (3) evaluating the quality of the products generated through collective intelligence systems.”7 Later in the article, they acknowledge that the organizational features of communities of peer production change over time; so, in fact, we must research our processes even as we engage in them—a terrifying thought for those who hate ambiguity.8

But in all of this, many of our organizations remain relatively hierarchical and control based, defined by their own drawn boundaries rather than by connection, and with a limited view of the resources lying fallow around them. In the midst of all that sits the idea of governance—that is, who really has the final say over what you as an organization should be doing?

A number of nonprofits that have recently run afoul of their networks of stakeholders have happened upon the startling fact that these are their ultimate legitimators; the final court is moving more and more into the public space in which social media connects those stakeholders to one another, allowing them to support or attack, or sometimes both.

A productive embrace of the fray, however, requires that one’s own integrity and values base be clear internally so that it can also be clear to the external world. Thus, your integrity becomes your ticket to credibility and a potential leadership role—that, and an active constituency.

There is, of course, much more to be explored here—for instance, the relationship between your face-to-face community, your online community, and your networks, which must always be attended to—but in the end, understanding and making good use of social media are now core competencies for many if not all of us here in the social sector.

Notes

- K. Prahalad and Venkat Ramaswamy, “Co-creating unique value with customers,” Strategy & Leadership 32, no. 3 (2004): 4–9.

- Ibid, 5.

- Ibid.

- Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg, “Communication in Movements,” in The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements, Donatella Della Porta and Mario Diani, eds. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2016), 372–73.

- Paolo Gerbaudo, Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism (London, UK: Pluto Press, 2012), 22.

- Sandra González-Bailón and Ning Wang, “Networked discontent: The anatomy of protest campaigns in social media,” Social Networks 44 (January 2016): 97.

- Yochai Benkler, Aaron Shaw, and Benjamin Mako Hill, “Peer Production: A Form of Collective Intelligence,” in Handbook of Collective Intelligence, Thomas W. Malone and Michael S. Bernstein, eds. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 175–202.

- Ibid.