November 13, 2014; Chicago Tribune

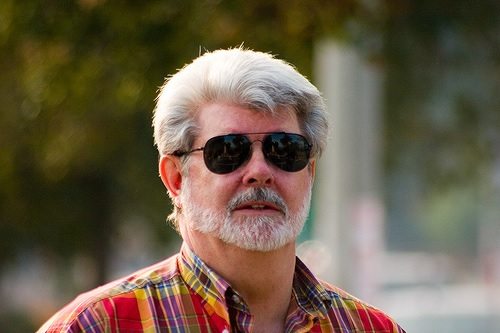

George Lucas and his eclectic museum of Star Wars memorabilia and other artifacts may still be a few parsecs away from a landing in the lakefront area of Chicago’s Park District, even though powerful mayor Rahm Emanuel is a staunch booster of the planned project.

Lucas’ first-choice locale was in the Presidio waterfront area of San Francisco, but that city rejected his proposal. He then decamped from the West Coast and chose Chicago for his tribute to his own legacy, ready to stock the museum with the many thousands of items from his signature creation and art he has collected over the years. The mockup of the George Lucas Museum of Narrative Art even resembles a taffy-pulled version of the Millennium Falcon, and for Chicago lakefront preservation (“open space”) activists, the debatable aesthetic value of the project is but another foothold in their uphill battle to stop the construction of the museum.

Friends of the Parks (FOP), one of the leading local preservation organizations, lived up to their promise to file a federal lawsuit, submitting their papers last Thursday, November 13th, in federal district court. Their central argument is that by remitting the lakefront property (including two large parking lots south of Soldier Field) to private hands, the City would be violating the longstanding public trust doctrine. Friends of the Park presents the claim in its federal complaint:

“The local governmental defendants (the city and Chicago Park District)…have no legal authority under state law or otherwise to convey any interest in or right of control of such trust property to a private individual or a private organization…as a free and open space accessible for navigation, fishing, boating and commercial activities on Lake Michigan.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The property in question is asserted under this doctrine to be held in trust for all of Illinois and that transfer to Lucas would require approval of the state government. Chicago Business reporter Greg Hinz posits that by supporting their case with a state-federal legal construct, the plaintiffs sidestep the allegedly cozy Chicago political machine led by Emanuel.

The defendants and their allies have already asserted that the property is not changing to private hands; the City entered into a memorandum of understanding with the Lucas group under which technically Chicago would maintain ownership of the land while Lucas would fully finance construction of his long-planned project. However, Lucas would have full control of the property in perpetuity so long as the museum continues operation. Thus, anti-museum advocates are suspect of the City’s sleight-of-hand with their concept of land ownership. Prior to filing federal suit, the plaintiffs’ original claim under the local Lakefront Protection Ordinance was viewed as a bad hand by many local pundits because it would have been adjudicated by a city board effectively controlled by the mayor through his several appointees.

The City, through its Law Department, has responded to the FOP lawsuit in federal court, saying that the suit is “legally baseless and defective on multiple grounds, which we intend to raise in a motion to dismiss.” In what amounts as more a press release than a legal argument, the City’s Law Department further extolled the controversial project:

“This museum is a substantial investment in Chicago’s cultural scene that will create green space, billions of dollars in local economic impact and hundreds of construction and permanent jobs.”

On the surface, the Lucas museum debate is an internecine tussle over a tranche of the local natural and manmade environment, pitting the Emanuel administration, Lucas, and some other Chicagoans against their brethren who disagree over the priorities embodied in this project meant to add to the existing lakefront cultural campus.

The current U.S. Supreme Court is no help to nature, either. Keep in mind their landmark 2005 decision in Kelo v. City of New London. By a 5-4 vote, they ruled that in some instances private developers could obtain use and control over land through eminent domain under which real property is seized by government, traditionally for the public good. The Court legitimized this practice as a “fair use” under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution, stating that economic development is itself a public good. Some view this pro-development trend as a conservative distortion of what this country views as “in the public good” through the prism of powerful political and business interests. Against the relatively limited resources and political clout of preservationists and individuals who simply want to limit human destruction of nature, economic forces may seem simply relentless and unlimited.

On such a roiling issue, this is not a recipe for Kumbaya in the Windy City no matter how the sides end up faring in court and on the ground. Beyond those people who seek to protect and maintain the lakefront as-is and limit further construction, many of the famously avid Chicago Bears football fans are exploding over the potential loss of their coveted tailgating turf in the targeted parking lots the museum would be built over. So, are George Lucas and the mayor on the Dark Side of the Force or master Jedi warriors bent on providing the Windy City a cultural boost?—Louis Altman